Introduction

Seventy years ago I had joined 7/2 Punjab Regt (now part of the Indian Army) in Arakan (Burma). This was a newly raised battalion consisting of mostly young soldiers who had carried out only basic training. Even most of the senior NCSs had not participated in any battle, except some had experience of Frontier warfare. But jungle warfare required deep knowledge of the area of operation, minor tactics peculiar to the area like sniping, camouflage, crossing of water obstacles (by swimming, wading across on self-made swimming aids), climbing of hills by carrying own weapon, ammunition and extra ammunition and light machine gun, etc.

I was also a raw young soldier aged 19 years with no experience of war but during a few months I was imparted basic training of young soldiers about field craft, weapon training, obstacle crossing, night marches with the help of compass and stars, digging of trenches and siting of weapons, track discipline and erecting of booby traps on routes likely to be used by the enemy.

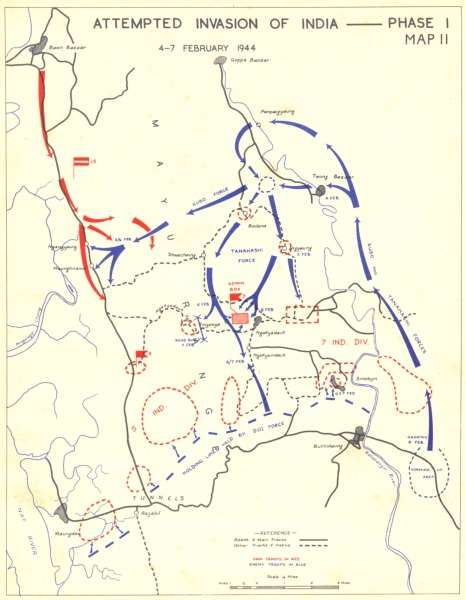

In the Battalion HQs news about the impending counter offensive of the Japanese was trickling in which was being passed to the company commanders but no serious effort was made to counter the enemy sudden attack. A sketch, depicting the enemy attempted invasion of India (4-7 Feb, 1944) is attached. Unfortunately our recce patrols and air recce had failed to locate the enemy forward concentration for the attempted invasion of India-Phase I.

The Battle of ‘Administration Box’ (Feb 1944) is a military classic which is keenly read by the students of military history. My article ‘The Battle of Administrative Box ARAKAN – Feb 1944 was published in the Pakistan Defence Review (winter 2001). This article is now being reproduced below for Defence Journal.

The Battle of Administrative Box Arakan – Feb 1944

Introduction

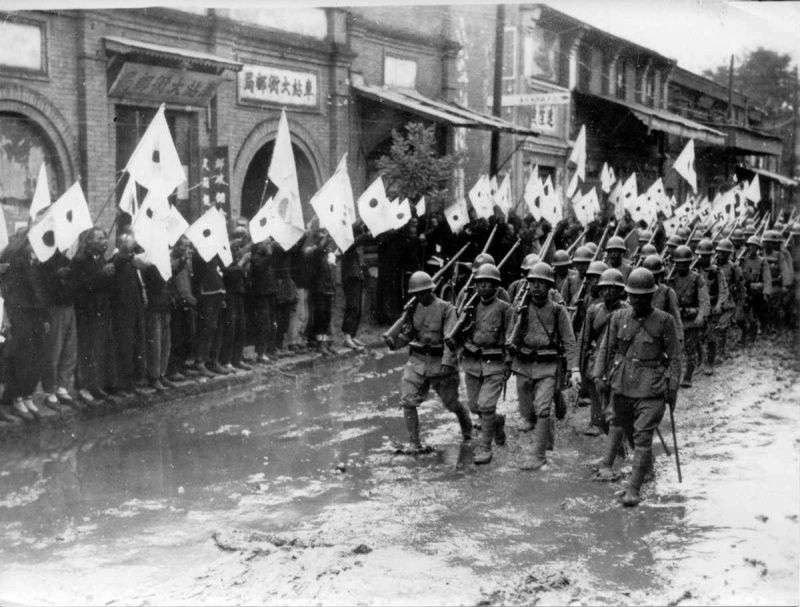

Prior to the Japanese counter offensive launched in February 1944 in Arakan against the 5th Indian Division and 7th Indian Division (now a proud formation of the Pakistan Army) of 14th Army, the Japanese had won resounding victories in Malaya, Singapore and Burma. The Japanese were considered superior for man to man and unit to unit, mostly due to their tactics of infiltration, long range deep penetration and outflanking movements. But the myth of prowess of the Japanese was shattered during February 1944 in the Battle of Administrative Box which was the first victory of the British Indian Army over the Japanese who were convincingly defeated with immense losses.

It was a defensive battle fought tenaciously with determination and steadfastness. The Japanese commanders were outwitted by timely, fast movements of platoons, companies, battalions and artillery subunits, through thickly forested areas infested with enemy for the defence of the Administrative Box.

I remember vividly many of the grim actions and memorable events of the Battle of Administrative Box because I as a young soldier was present with my battalion, serving in the 7th Division. I have tried to highlight some salient points of this battle, the reasons behind failure of the Japanese counter offensive and success of the 15 Corps.

Topography

For the benefit of readers a brief description of Arakan is essential. Arakan was an area of densely forested hills with villages, invariably situated on the banks of streams/nullahs, which had paddy fields. Even flat areas were partly undulating and partly covered with trees and elephant grass.

The Mayu range was about 2000 feet high. It ran from north to south and was the dominating feature with numerous low detached hills scattered for miles down below. On the west of the Mayu Range, the town of Maungdaw was situated on the bank of the River Kalapanzin. The Mayu Range was crossed by only one metalled road, through two tunnels which was once a narrow gauge railway.

The Kalapanzin River flowed from north to south, fed by many flowing streams/nullahs. The valley between the Mayu Range and the Kalapanzin River was about 8 to 10 miles wide, intersected by a series of narrow ridges, from 50 to 150 feet high, all covered with bamboo jungle and elephant grass. Ngakyedank Pass, a tough gradient mule track was converted into a fair weather motorable road and connected Bawli Bazaar road with the Kalapanzin valley. A few existing tracks were also converted into fair weather roads for heavy vehicles, jeeps and artillery guns. During the monsoon, from June to September, vehicles bogged down and troops were unable to move quickly and freely. Malaria was rife and most of the jungle area was full of leeches. The local Muslims were friendly whereas the Maugh were pro-Japanese. During the dry season, the morning mist covered the valleys from before dawn to 10 a.m. Arakan was an area of great natural beauty, with fascinating views of mountains, jungle, streams/nullahs and green valleys.

Relative Strength

The 15th Corps of the 14th Army (General Slim) was deployed on both sides of the Mayu Range with 5th Division on Maungdaw-Bawli Bazaar axis and 7th Division (Major General Messervy – later the first C-in-C of the Pakistan Army) in the Kalapanzin Valley. The Corps was supported with full compliment of supporting arms and services. 7th Division also had the support of a tank regiment (less squadron), a battery of light anti-aircraft guns and a battery of heavy guns. “V” Force detachments with the help of friendly locals were operating deep behind the enemy lines and proving information. 26th Division was concentrated in Chittagong as reserve. A few squadrons, each of Spitfires and Hurricanes, were available for close air support. Bomber squadrons were also available.

By January 1944 the strength of the Japanese troops against 15 Corps had doubled. The Japanese 55 Division was over 30000 strong. The bulk of 1/213 regiment of 33 Japanese Division and a brigade of Indian National Army were placed under command 55 Division. The elements of 33 Division were also operating in Kaladan, about 15 miles away on the left flank of 7th Division, against 81 West African Division. The Japanese troops were provided with extra artillery support and animal transport. Dumps of supplies were reported behind the forward Japanese positions, facing 15 Corps. The Japanese air force had become very active in January 1944.

The Japanese infantry facing 6th and 7th Divisions was superior in numbers but the Japanese artillery was inferior and also they had no armour. However some anti-tank guns were made available. The Japanese zero fighter aircraft was superior to the Hurricane but the recently arrived Spitfire proved better in the interceptor-fighter role.

Between Dec 1943 and Jan 1944 the troops had an upper hand in patrolling. In a series of toughly contested actions most of the units had captured many hills of tactical importance. We felt proud and elevated to have killed Japanese soldiers.

Plan of the Japanese Counter-offensive–“HAGO”

The aim was first to destroy 7th Division and then 5th Division as a preliminary phase to a limited advance towards Chittagong. The Japanese High Command was confident that the arrival of their forces, accompanies by troops of the Indian National Army in East Bengal would be a signal for open revolt which would paralyze the supply lines of the 14th Army.

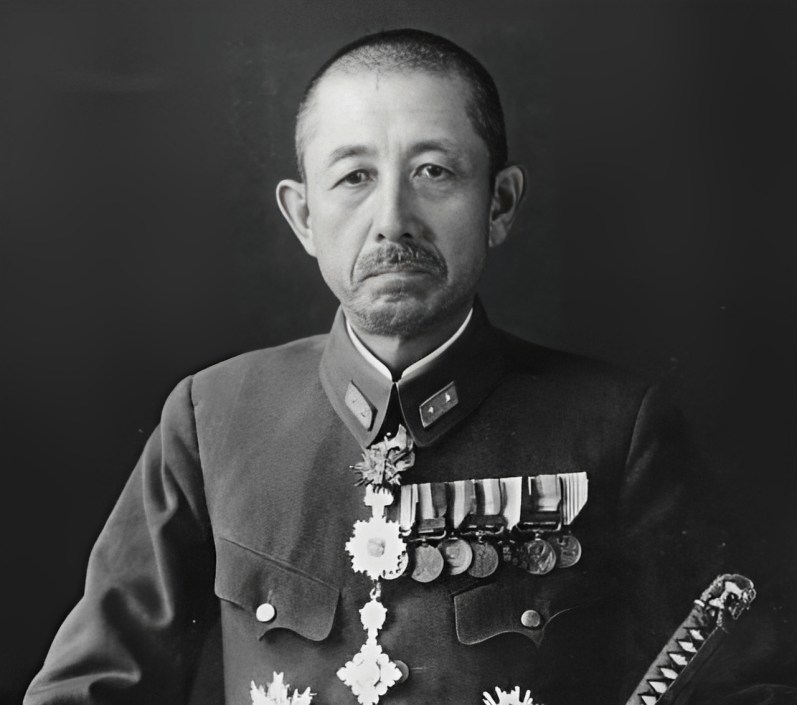

Maj Gen Sakurai, tactician, resolute and skillful, the infantry commander of the 55 Division was appointed as the commander of the force which was to attack 7th Division from the rear. The force consisted of 4 infantry battalions, an engineer battalion and major portion of 1/213 regiment of 33 Division. The force was provided with detachments of mountain guns and anti-tank guns. The total strength of the force was 7000 to 7500. Colonel Tanahashi, commander of 112 infantry regiment was entrusted with the task of capturing and blocking of the Ngakhedank Pass and destroying the 7th Division base of Sinzweya known as the “Adm Box”. The Japanese 2/143 regiment: (Col Matsuo) was to clear and hold the river Kalapanzin crossing at Taung for 112 infantry regiment whereas 1/213 regiment (Col Kubo) was entrusted with the task of blocking the Bawli Bazaar road by crossing the Maunghrma Pass and also to counter any advance down the river from Goppe.

The counter offensive was to be launched on the night of 3/4 Feb 1944. It was confidently calculated that the action of the Sakurai force would throw the 7th Division into confusion and its final destination was to be carried out by a frontal attack by 143 regiment (Col Doi). Col Tanahashi was then to cross the Mayu Range and cut off the 5th Division and to be driven into Nafestuary, while 1/213 regiment during this period would hold off any force coming from Bawli Bazaar road. The Japanese High Command was certain that due to encirclement 7th Division and 5th Division would retreat in panic, leaving all supplies, guns, transport, ammunition, tanks and many prisoners behind.

The Japanese slogan for the operation was “HAGO” which meant “Headlong Attack”.

Preparation – 15 Corps

In Jan 1944, from all sources it was evident that the Japanese would launch a counter offensive against 15 Corps. A flanking hook was expected to be delivered from the left along the Kalapanzin River. A gap of about 10 to 15 miles existed between the 81 West African Division and 114 Brigade of 7th Division. Small scale infiltration was also possible through the gaps between 33 brigade (Brig Loftus Tattenham – later GOC 7th Division Pakistan Army) 114 Brigade and 89 Brigade. 7th Division had been deployed on a wide front with wide gaps between the units and brigades. The division was without depth. During day time movement through these gaps was not possible. It was correct to presume that the enemy had been carrying out ground recce of the rear areas and all the gaps and open flanks were known. Formations and units were ordered to hold fast, if cut off.

On the night of 2nd/3rd Feb 1944, 89 Brigade (my battalion was part of it) was withdrawn from the forward positions as reserve to carry out preparations for the capture of Buthidaung.

In view of the expected Japanese counter offensive, essential stores, rations, ammunition and small arms were dumped on a few air fields in the depth areas for air drops in the operational areas, when and where required. Transport aircraft were also earmarked for air lift. Simzweya Base, east of the Ngakyedauk Pass, was converted into the divisional “Adm Box”. All types of ammunition, ration and essential stores in great quantity had been dumped there. ‘B’ echelon of most of the units and detachments of Ordnance, Supply, EME and Medical were located there. The tank regiment (less a squadron), AA guns, medium and heavy guns were deployed there. Thus the garrison with the exception of the tank regiment, personnel and gunners consisted mostly of troops of administrative units.

The Administrative Box was an open area of circular shape, about a mile long and half a mile broad. It was surrounded by low hills, 100 to 200 feet high, covered with thick bushes and trees. The Mayu Range overlooked the Adm Box from the west. The fair weather motorable road and few motorable tracks passed through it. The Ngakyedauk Chang (nullah) ran along its southern edge and to the west the ground rose steeply to the main ridge.

26th Division already concentrated in Chittagong, was alerted to move to Bawli Bazaar at short notice for counter attack. The 36th British Division (less one brigade) was also kept ready.

Since 15 Jan 1944, the enemy air force suddenly became active and bombing and strafing of forward and rear administrative areas was carried out. Adm Box also became a frequent target of the enemy long range guns. Shelling of defensive positions had also become intense. These actions of the enemy provided training to the troops in camouflage and concealment. This battle inoculation proved useful during the Japanese counter offensive.

The Battle

On the night of 3/4 Feb a big column of Japanese infiltrated through a gap of 2 to 3 miles between 14 brigade and the river Kalapanzin via Kyauk yit and Pymishakala. Few Japanese parties with outflanking movement passed through the gap between 114 brigade and 81 West African Division. Some parties infiltrating through the gaps between the river and 33 brigade via Sinclyin were also detected at night by patrols. Moving along the river, important heights enroute were occupied to facilitate smooth movement. That night, a mule part of 114 brigade moved parallel to the enemy mule column and took it to be theirs, returning after unloading supplies for the forward positions. A recce patrol of a British unit found an Indian muleteer with a bogged-down mule cart and thinking him to be own soldier helped him to regain movement. 7th Division had no mule cart and obviously it was a Japanese cart taken by an INA soldier.

As the morning mist lifted from the posts of Somerset, Light Infantry of 114 brigade soon engaged the enemy but the Japanese parties kept on moving towards the north and soon captured the base of Taung Bazaar. The enemy, as reported in considerable strength, was moving west and south-west direction and its artillery and air force also became active. Adm Box and the forward positions were the main targets.

At about 0930 hours on 4 Feb, 89 brigade, on orders, moved north with two battalions up. 7/2 Punjab (my battalion) was ordered to capture Taung Bazaar. Enemy artillery shelling and air force strafing tried to disrupt the movement of 89 brigade but the advance continued briskly. As the 3” mortar officer I was with the vanguard company. Enroute enemy snipers and nuisance patrol tried to harass the movement but they were brushed aside promptly. Both the forward battalions were directed to Badana. First big encounter of 7/2 Punjab took place in the afternoon at Ingyaung. Enemy parties, seen passing through a gap were engaged by machine guns and mortars. Own artillery also started shelling the area. According to the diary of a dead enemy officer, lot of casualties were suffered that day by them. The enemy also retaliated with artillery shelling and machine gun fire. 89 brigade HQ and a British battalion were at Linbabi. The rear route was cut off but the determined defence put up against enemy counter attacks by the forward battalions for two days undoubtedly played a large part in the eventual defeat of Sakurai force by causing it to suffer a lot of casualties and loss of precious time. 89 brigade also suffered casualties and due to enemy actions, supplies were not received.

In the meantime on 5/6 February night the Japanese had managed to reach close to the 7th Division HQs. At dawn on 7 Feb a large party attacked and after some stout resistance HQs 7th Division was over run. Some officers, many signalers, clerks, drivers and batmen were killed. The Division HQs was without its defence company. The GOC, alongwith the commander artillery and few others, miraculously saved their lives and after a long tiresome march through the area infested with the enemy, reached the division Administrative Box in the afternoon of 6 Feb. The GOC immediately assumed command through a unit wireless and ordered its brigade commanders to hold fast. The effect on the troops everywhere was electric. The GOC had been in the Adm Box barely half an hour when the enemy opened their attack.

As the fate of the GOD 7th Division and his staff was not known before their arrival, in the afternoon of 6th Feb, the Corps Commander had ordered the commander 9 brigade to take over the defence of the Adm Box and hold it to the last. The perimeter was divided into sectors and vital areas were allotted for defence to the troops of fighting arms.

33 brigade and 114 brigade had immediately readjusted their positions for all round defence. 33 brigade was holding area Tatmakhali, Sinohbyina, point 182 and Mont Blanc. 7th Division gun area was in the rear of the Brigade HQ, 114 brigade had also been given the task to protect the left flank of 33 brigade and provide protection to the gun area. A mobile reserve by each brigade was kept ready for counter attack and occupation of vital areas. They had organized their own administrative areas to receive air drops. Companies and platoons were switched to provide all round defence and frittering enemy assaults.

After a night, withdrawing through an area infested with the enemy, 7/2 Punjab reached Awlanbyin but was attacked in the morning of 7 Feb. The battalion HQs was cut off from the rest of the battalion while companies and even platoons found themselves isolated. Two Muslim companies, commanded by subedars were isolated on Awlanbyin without food and with pouch ammunition only for four days during which they beat off attacks and inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy trying to use the east to west tracks.

The units and companies of 89 brigade were moved from place to place to keep the enemy routes under fire and to provide protection of the Adm Box. Tanks were frequently moved to provide close support to the units and companies engaged by the enemy and often imposed caution on the enemy and kept a considerable force tied down. For providing close support to own troops many a time guns had to switch through 180 degrees.

On 6/7 February night, the enemy infiltrated into the areas of the Main Dressing Station located on a jungle clad hillock in one corner of the Adm Box. The enemy killed most of the wounded and the doctors and only a few were able to save their lives by hiding and later told the tragic tale of enemy atrocities. The enemy was driven out by a counter attack. By the morning of 7 Feb the enemy was firmly established on the Ngakyedauk Pass and 7th Division was effectively isolated as far as land communication was concerned.

In the Adm Box troops were told not to move at night under any circumstances. Anything moving was to be shot because the enemy would try to infiltrate silently during the dark hours. If any defender left his trench he must expect to be shot by his comrades. No conversation above a whisper was allowed.

The enemy had occupied some of the higher hills overlooking the Adm Box and brought a few mountain guns and opened fire at point blank range. A few vehicles and the ammunition dump were set on fire but the enemy guns were soon silenced by the guns deployed in the Adm Box and their escorting party was driven off by counter attack but the fire and explosions which went on for many hours made a large part of the area dangerous. Enemy’s long-range guns shelled the area and aircraft also dropped bombs and created havoc but the situation was brought under control with many sacrifices with cool courage. Since this incident till the end of the siege on 24 Feb, never a day or night passed without an attack on some part of the perimeter and at the same time, the enemy artillery continued harassing fire. The enemy also suffer casualties.

On 7 Feb an enemy messenger from the Japanese commander carrying two important messages was killed east of the Kalapanzin by a patrol of 114 brigade. The messages were recovered from his dead body. One message instructed commanding officer 2/144 regiment to advance that night to a hill southeast of Awlanbyin, overlooking the gun positions of 7th field regiment and attack towards Awlanbyin. There was no doubt that the attack would have caused 7th Division lot of difficulties. The other message gave Sakurai’s call signs and frequencies and the intelligence branch of 14th Army later confirmed that the loss of this message caused disruption in the Japanese communications. The Japanese also stated that during the period Sakurai was out of touch with Tanahashi, commander of the main striking force.

The enemy made many suicidal efforts to reach and destroy the tanks located in the Adm Box. A large party, during daylight, descended from a hill with fixed bayonets, charged the tanks but the tank and artillery gunfire at point blank range killed all of them. I was a witness to many such charges and attacks.

On 11 Feb the first supply drop in the Adm Box was carried out by low and slow flying Dakotas. They dropped bags of atta, rice, ammunition, medical supplies, etc. The airdrop raised the morale of troops. Airdrops of essential items also took place in the brigades Adm areas.

The enemy, between 10 and 13 February had captured a few vital hills overlooking the Adm Box but intense tank and artillery fire at point blank range inflicted heavy casualties. The firing had burnt the undergrowth of the hills and the unburied and dismembered bodies of the killed enemy were scattered everywhere. By now, skeletons of burnt vehicles, guns, damaged tanks and abandoned carriers were seen in the area of Adm Box. Casualties had reduced the garrison which mostly consisted of Engineers, EME, Animal Transport, Ordnance and Artillery troops. Only three companies of a British battalion were defending a few vital areas. Due to continuous pressure and capture of some hill features overlooking the perimeter by the enemy, 7/2 Punjab was order to abandon Awlanbyin and take over the defence of the southern vital area of the Adm Box. One company of the battalion was left to hold the abandoned height of Awlanbyin, well supplied with ration and ammunition. The company, during the next ten days, inflicted very heavy casualties on the Japanese supply parties and reinforcements trying to reach Tanahashi and Kobo force but in spite of repeated efforts the enemy failed to dislodge the company.

On arrival in the Adm Box, 7/2 Punjab was assigned the task of defending the vital feature in the south of the Adm Box. The next day enemy aircraft dropped a few bombs in the Adm Box. The ammunition dump was set on fire and 3 officers were killed and many were wounded. I, as Mortar officer was given the task of defending the medium and AA guns against any Japanese ground attack. In the afternoon I was discussing the direction, degree and distance of the newly occupied hill by the enemy overlooking the Adm Box with the gun position officer when suddenly a shell of enemy mortar landed where we all were standing. It killed the gun position officer and wounded 3 men. Immediately a troop of medium guns engaged the enemy position at point blank range and blasted it.

The counter attacks by units of 7th Division outside the Adm Box were blocking the supply parties of the enemy and also it had become difficult to evacuate the casualties. Pressure from the west was increasing on the enemy as a brigade of 5th Division began to advance down to the Ngakyedank Pass and patrols of 26th Division, moving south from Goppe, were making their presence felt. According to the Japanese plan, by 13 February, 7th Division would have been destroyed but there was no indication of its defeat or destruction. On 14 February the Japanese High Command ordered an all out attack. The order was picked up on wireless and all the units were alerted to stand fast. The attack on the Adm Box did not succeed.

The garrison was getting exhausted due to the casualties of which about 500 were in the dressing station. By 15 February the British battalion of 89 brigade and the headquarters of 89 brigade also moved into the Adm Box minus the mule column which had been ambushed by the enemy. The mules stampeded and disappeared into the darkness to the south and remained in hiding in the jungle. The column, after two days, made its way into the Adm Box. The evacuation of over 200 severely wounded started by an artillery Auster aircraft from the Kwazon Box of 114 brigade. A patrol of the tank regiment on 16 Feb made contact with a patrol of 26th Division. This division was operating on Goppe – Taung – Kwazon axis along the Kalapanzin River. The British 36th Division was operating on Bawali Bazaar-Maungdaw axis. The sound of heavy fire from the north and west indicated that the advance of 26th Division and 5th Division was making convincing strides against the enemy.

33 brigade was holding a very wide front. Though the units remained cut off for a week but with the support of tanks, some vital features were captured and the enemy, with heavy losses, was driven out. Aggressive patrolling also blocked the enemy parties carrying supplies and reinforcements for Tanahashi and Kubo forces. On 21 Feb a carrier convoy from the Adm Box got through to the HQ of 33 brigade without opposition and it became evident that the enemy had started to break.

114 Brigade, operating east of the river Kalapanzin was able to recover some of the abandoned positions occupied by the enemy.

On 21 Feb a large enemy party, having lost its way, entered the Adm Box from the east. They were all killed by artillery shelling and small arms fire. On 22 Feb an enemy party ferociously attacked the anti-aircraft guns and reached within 200 yards of the 7th Division headquarters but they were repulsed with heavy casualties. At midday on 23 Feb after a fierce fight, contact was established between the units of 5th Division and 7th Division operating to open the Pass and on 24 Feb, the Pass was opened to traffic. A unit of 26th Division crossed the Kalapanzin and established contact with 114 brigade of 7th Division.

On 24 Feb all the wounded were evacuated via the Pass. From various units and patrols, affirmation about the withdrawal of enemy parties was being received. The siege of 7th Division had been broken and according to the historian of the ‘Golden Arrow’ “The completeness of the enemy defeat is perhaps shown by the fact that all General Messervy’s kit that had been left in Laung Chaung (7th Division headquarters location) was recovered from various dead bodies, including his personal family photographs and his ‘brass bat’ which was retaken into use and worn for the rest of the war”. General Slim, commander of the 14th Army sent the following message:

“The Battle of Arakan was the first occasion in this war in which a British Force (over 75% were Indian soldiers out of which at least 30% were Muslim soldiers from various areas which, in August 1947m were included in Pakistan) has withstood the full weight of a major Japanese offensive – held it, broke it, smashed it into little pieces and pursued it. Anybody who was in the 7th and 5th Indian Divisions, and was there, has something of which he can be very proud indeed.”

Conclusion

By smashing the last enemy resistance on 24 February on the Ngyakydauk Pass, the Battle of Adam Box had ended in triumph for the troops of 15 Corps. The troops of 7th Division had particularly proved their prowess by valiantly standing fast. The scattered parties of Sakurai Force had retreated back to their bases. In all the actions from 4 to 24 February, 1944 about 5500 enemy soldiers were killed. The enemy had lost nearly all its guns, a great quantity of small arms, few hundred mules and dumps of supplies scattered all over the operational areas. Only the severely wounded 10 prisoners of war were captured, one was force to admire the stoicism of the Japanese soldiers, who although exhausted, hungry and defeated, refused to surrender. Even when caught in the open under heavy fire they would prefer to be killed or commit suicide. The Japanese were tough, well trained and masters of junior tactics.

The reasons of the defeat of the Japanese and victory of 15 Corps are briefly appended below:

Complete breakdown of administrative system because the Japanese commanders had assumed that 7th Division troops would retire in panic and supplies, ammunition, vehicles and guns would be captured.

As a result of the aggressive action by troops of 7th Division, only a trickle of supplies and reinforcement managed to reach the forward troops.

Japanese supply lines had been hurried from the sea and from the air, therefore the remedy of the situation was not possible.

The line of communication from the rear to the fighting forces and back was unsafe as such evacuation of casualties was not possible.

The fighting qualities of the opposing troops were underestimated by the Japanese.

The Japanese artillery was inferior and badly handled but for close support, 4 mortars proved useful.

During the siege of 7th Division the Japanese air support for their ground forces was sporadic and lacking desired effect.

At least 20 air supply drops at different places were carried out but the Japanese air force interference was negligible as only one Dakota was damaged. Strangely, the Japanese high command had failed to visualize the supply drops by air for the besieged troops of 7th Division who were getting every important item. Here, an extract from the diary of a wounded enemy officer is quoted aptly highlighting the anguish and miserable situation faced by them. It reads, “Planes are bringing whisky, beer, butter, cheese, jam, corned beef and eggs in great quantities to the enemy. I am starving.”

The strategy of the Japanese was bold because they were able to concentrate superior forces at vital points against the widely deployed 7th Division and from 4 Feb to 12 Feb they attacked at those points but failed to achieve success.

The Japanese plans were rigid and failed to flex the same according to the situation. Their commanders were dogmatic.

Tanahashi, Hanaya, Sakurai, Kubo and the rest made immediate applications for permission to commit Hari Kari but the emperor refused on the ground that this sudden loss would cause grave command problems.

15 Corps Success – Reasons

The sudden infiltration and outflanking movement of the enemy against the units of 7th Division had achieved surprise but soon they reacted aggressively and stood fast. They met the onslaught with courage and confidence.

The gaps and routes frequented by the enemy were blocked, with available meager troops and kept under small arms and artillery fire. Positions of units were quickly readjusted according to the situation, even by taking a turn of 180 degrees. The administrative areas of units and formations had become front line positions.

The initial aggressive counter actions of the troops of 7th Division surprised the enemy commanders which resulted into loss of precious time, supplies, ammunition and casualties of their troops.

Availability of superior artillery for close support and engaging deep enemy targets.

Timely arrival of 26th Division and 36th Division for counter attacks on the enemy positions from the rear.

Supply drops by air on different areas helped the besieged units.

About 1300 tons of supplies were dropped.

Tactical air support, as and when required, was available which inflicted heavy losses on the enemy.

Availability of tanks for immediate counter attack and close support even at point blank range.

The commander of 14th Army (General Slim) was cool, foresighted and superior as a strategist. He was not rigid and allowed necessary changes in operation plans according to prevailing situation, for achieving his mission. He had correctly visualized the timings, expected routes and approximate strength of the Japanese counter offensive and therefore preparation were made to meet the onslaught.

During the battle of Adm Box, 7th Division had suffered 1579 casualties whereas 5th Division, 26th Division and 36th Division had suffered 993, 612 and 118 casualties respectively.

Bibliography

- The War Against Japan, Maj Gen S. Woodburn Kirby, Capt C.T Addis RN, Brig M.R. Roberts, Vol III

- Spearhead, Henry Maule, General

- Golden Arrow, Brig M.R. Roberts

- Defeat into Victory, FM W. Slim

- Campaign of the 14th Army 1943-44, FM W. Slim

- Report by the Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia, 1943-45, Vice Admiral Mountbatten.