“There is a general agreement that the world order is changing, but considerable disagreement about how it is changing. Communicators variously locate this change in a ‘power shift’ from West to East, a trade in superpower status between the United States and China, or a transition from an era of biography to one of uni-polarity, multi-polarity or even non-polarity…….. the smooth functioning of international order: globalization, US militarism, dynamics of revolution and counter-revolution, finance capital, climate change, the rise of non-state actors, new security threats, the dislocating effects of information and communication technologies (ICTs), and more.”1

The collapse of the Soviet Union changed the norms of global politics having far reaching impact on European politics. This breakup resulted in creation of 15 sovereign states with huge displacements.2 Approximately, 25 million ethnic Russians found themselves stranded in 14 newly independent states (NIS), while the Russian Federation (the world’s largest territorial state) was left with almost similar number of non-Russian citizens.3 The end of the Soviet Union was the end of an empire and a political ideology that ruled major part of the world for decades. However, there was an opportunity for the successor states for building new states and to improve fundamental political and economic restructuring.4

With new opportunities there were some after effects of the dismantled USSR. In Russia the problems of national identity and the course of Russian politics remain uncertain. In the year 1991, Boris Yeltsin5 elected first president of the Russian Federation. On his second term as President of Russian Federation he immediately ordered his aides to develop a ‘national ideology’ (or ‘national idea’) that may unite the citizens of Russia,6 in contrast to the previous ideologies that caused awful damages to Russian Federation. A government committee was established to develop this idea but had ineffective results. The idea had to endure the post-imperial suffering of losing both its external (East European) and internal territories. Also the pain of transitions in political and economic restructuring required to establish democracy and new markets.

More than 60,000 people were killed or were reportedly missing and more than one million refugees migrated to the territory of the former Soviet Union.7 Analysts maintained that in spite of the uncertainties in Russia and the adjoining states there was relative peace vis a vis Yugoslavia. This shaped the early years of Russian Federation, with periodical creation of newly independent states (NIS). Ukraine was amongst these NIS, however, gained significance due to presence of Crimea and Black Sea Fleet.

History

Ukraine was earlier known as “Kievan Rus” till 16th Century. Kiev was the major political and cultural center in Eastern Europe in the 19th Century. In 10th century Kiev, adopted the Byzantine Christianity. The Byzantine Christianity was ended with the Mongolian conquest in 1240 A.D. Kiev remains under Polish influence and Western Europe from 13th to 16th century. Ukrainians were divided into orthodox and catholic faithful while negotiating on the Union of Brest-Litovsk in 1596 A.D. In 1654 A.D., Ukraine asked the czar of Muscovy for protection against Poland following endorsement of the Treaty of Pereyasav8 recognizing the suzerainty of Moscow and later became part of Moscow.

After the Russian Revolution9 of 1917, Ukraine first declared its independence on 28 January 1918 followed by conflict and fighting amongst various groups. The unrest invited the Red Army to intervene and by 1920 Ukraine again became a Soviet republic. With the Soviet accession of Ukraine, it was considered as founding member state of the then Union of Soviet Socialist Republic (U.S.S.R). Later in 1930s the Soviet government’s enforcement of collectivization10 encountered peasant resistance, resulted in the confiscation of grains from Ukrainian farmers. Though the enforcement turned disastrous and caused acute famine. Millions died in this famine.

In 1991, the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republic (the U.S.S.R) ceased to exist. Ukraine became virtually independent while hosted largest number of Russian expatriates. Russians constitute almost fifth of Ukraine’s 52 million inhabitants. They were concentrated in eastern Ukraine, bordering Russia and Crimea. The polarity and disposition of Russian settlement created huge problems of identity crisis and other problems of transition. The future of Ukraine than became depended on the minority question correlating with its stability. From that period onwards, there was a friction between Ukraine and Russian Federation over Crimea, the Black Sea Fleet and the supply of natural gas and oil by Moscow.11

Maintaining a unique identity became a major question in Ukrainian politics with several other factors molded its identity and nationalism. Firstly, Ukraine is a multi-ethnic state with apparent group representing less than three quarters of the total population. There are large no of Russians as well as other minorities, but many ethnic Ukrainians are in fact Russophones.12 Even President Leonid Kuchma13 is much more comfortable speaking Russian than Ukrainian.

Geography usually played important role in forming national identity or nationalism. The Dnipro (or Dnieper) River primarily divides Ukraine culturally, politically and geographically: the west bank looks more toward Europe and its independence; the east banks more toward Russia and Russophone culture.14 Andrew Wilson claims that the Ukrainian nationalism is a ‘minority faith,’ favored only by a minority of the ethnic Ukrainian population.15

Stalin’s forced collectivization earlier resulted in death of more than five million Ukrainian.16 For that purpose at the time of its independence an attempt at ethnic nationalism would become risky and electorally unwise. There were dangers of polarization considering large numbers of Russian and Russophones voters. This was illustrated during the March 1998 parliamentary elections. The communist party of Ukraine having strong support among Russian minority in the eastern part of the country won the largest number of seats.17

The movement for Ukrainian independence started off with the breakup of former Soviet Union. Vladimir P. Lukin, Chairman, Russian Parliament Foreign Relations Committee, presented a series of proposal commonly known as the Lukin Doctrine18 that included the return of Crimea and the Black Sea Fleet19 to Russian Federation.20 The Russian Duma, moreover, passed a resolution declaring Nikita Khrushchev’s 1954 gift of Crimea to Ukraine as unconstitutional. The Duma further endorsed a resolution increasing pressure for controlling vital natural gas sales to Ukraine. They also tried to attain certain political goals, such as Ukrainian concessions on the Black Sea Fleet, military bases in Crimea and better Ukrainian cooperation in the Common Wealth of Independent States (CIS).21

The Yeltsin government, however, kept such pressures within limits, it did not threaten the independence of Ukraine. In May 1997, Yeltsin and Kuchma signed a wide-ranging ten-year Treaty known as ‘Treaty of Friendship’22 for better cooperation and partnership. The peaceful breakup of the Soviet Union aided the development of more civic-based nationalism in Ukraine. There was a possibility that armed conflicts than might have greatly encouraged nationalistic extremists both in Russia and Ukraine. It also enjoyed wide-spread support across all ethnic and linguistic groups. In December 1991, 90 percent voted for independence and 62 percent for Leonid Kravchuk’s election as president in the Ukrainian referendum. The polarity within Ukraine made things complex unlike the Russians expectations. Ukrainians on the west bank of the Dnipro emphasized independence from Russia.23

“…. The Ukrainian leadership has helped restrain nationalist pressures for the creation of an exclusivist national identity and restrictive ethnic nationalism. While they looked westward to Europe, Leonid Kravchuk, who started as a moderate nationalist president, was careful to maintain a dialogue with Russia, to sustain important economic relations, and to pay at least lip service to the goal of making the CIS effective although not supranational.”24

NATO Factor

Another important factor that greatly influence the regional politics in Eastern Europe and the Russian hostility towards it adversaries in the West was formation of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). It was an inter-governmental military alliance based on a Treaty signed on 4 April 1949. The organization constituted a system of collective defense with twenty eight member states across North America and Europe agreeing to mutual defense. NATO’s headquarters were based in Brussels, Belgium. An additional 22 countries participate in NATO’s Partnership for Peace program, with 15 other countries involved in institutionalized dialogue programs. The joint military spending of all NATO members is more than 70 percent of the world’s defense spending.

The Cold War led to a rivalry with nations of the Warsaw Pact (founded earlier in 1955). NATO also shrinks the possibility of defense against a prospective Soviet invasion and expansion of the independent French nuclear deterrent. Consequence were French withdrawal from NATO’s military structure in 1966 for 30 years.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the organization was drawn into the breakup of Yugoslavia, with the military intervention in Bosnia-Herzegovina from 1992 to 1995 and later Yugoslavia in 1999. Politically, the organization sought better relations with former Warsaw Pact countries, of which, several joined the alliance between 1999 and 2004.

The Article 5 of NATO’s Charter facilitated support any other member state subject to an armed attack or subversion from any non-NATO state. Thought the Article was invoked only once after 11 September attacks on World Trade Centre in New York in the year 2001 with deployment of troops in Afghanistan under the NATO-led ISAF. The other Article 4 which is less compelling and modestly invokes consultation among NATO member states has been invoked 4 times, thrice in turkey and once in Poland.25

The Russian democrats consistently opposed NATO enlargement out of their fear that it would affect Russian domestic politics avoiding the idea of any military threat from the West. The Russian Federation was also afraid of NATO enlargement and its movement closer to the Russian borders with the idea that it would strengthen authoritarian and ultra-nationalistic forces infuriating ordinary Russians. The Federation remains in compliance with NATO while ordinary Russians seems indifferent.26

In May 1997, Russia and the alliance signed NATO-Russian Founding Act, abetting political dialogue. A NATO-Russian Permanent Joint Council (PJC) was also established that would allow Russia to negotiate but not to veto. The Russian doubts started to diminish as soon this PJC was established assuring new member states with consent that no additional substantive combat forces would be established.

A NATO experts have observed as follows,

“We often look back on the first years of the NATO-Russia partnership as a necessary but unpleasant transitional phase, brought to a decisive close with the 1999 Kosovo crisis. Yet in those difficult years, we succeeded in managing Europe’s most pressing security crisis – the chain of civil war and ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia – and in doing it together. Russia became the largest non-NATO troop contributor to NATO-led military operations, a distinction it held for more than seven years.”27

Russian believe that the enlargement of NATO was potentially dangerous both for the democratization and resettlement of Russian migrants. The Russian Federation was deeply concerned about further NATO enlargement. The Baltic States continue to thrust towards NATO membership besides Russian opposition.28

NATO enlargement considered to have deleterious effects on minority issues in Eastern Europe and Baltic State states. The prospective membership in NATO helped to induce Hungary and Romania in 1996 to sign a treaty that was meant to settle outstanding problems, including those relating to Magyar minority in Romania.29 Hungary was more willing to join the alliance, yet, had to make significant compromises on the ethnic and minority issues.

Ukraine signed a charter on typical partnership with NATO in Madrid on 9 July 1997. The democratic process gradually improved the conditions of the Russian minority in Ukraine. NATO’s gradual access towards Russian bordering states anticipating the Baltic memberships developed a sense of insecurity even in a moderate Russian leadership. As a result, the Russians increased pressure on the surrounding states to provide Moscow with security assurances, before aligning themselves with NATO. Ukraine continued to be Russia’s most trusted NIS neighbor and though comes under immense pressure.

United States was also considered as a belligerent country for Russians and its allies during post-cold war period, till date. A survey found that 39 percent of the Ukrainians thought that the United States was the greatest threat to their country as compared to only 15 percent who feared Russians themselves.30 A natural, normal, voluntary integration would not represent the re-creation of a Russian territory. Integrations would be driven by genuine political and economic need and rationality in contrast to the imperial ambitions of the Gorchakov/ Primakov31 type of “single economic area.”32

Ukraine was never in a position to block Russian imperial ambitions. As a case study, its importance in the European balance of power did not serve Poland well in the inter-war period. Analysts than believed that NATO enlargement particularly combined with election of a nationalistic leader to succeed Kuchma that would made Ukraine inflexible on the Crimean dispute. There was a possibility that this arrangement would minimize prospects for continuing the current peaceful relations between the Russian Federation and Ukraine.

The Present Crisis and its implications

“….the power gap that served as the bedrock for a core periphery international order is closing. It is being replaced by a decentered order in which no single power- or cluster of powers – is pre-eminent: the world is undergoing a shift from a globalism centered in the West to a ‘decentered globalism’.”33…..highlighting the strengths and weakness of the four most prominent forms of capitalist governance: liberal democratic, social democratic, competitive authoritarian and state bureaucratic. We than access the prospects for inter-capitalist competition and cooperation.”34

In the case of Ukraine and Kazakhstan, the relatively tolerant attitude and policies towards the Russian minorities may be interpreted in many ways. Firstly, are these states persuaded of the benefits of civic nationalism? Secondly, are they confident that demographic trends (shaped in part by ethnic Russian immigrations) and/ or linguistic assimilation will in the long term resolve matters entirely in favor of the titular nationality?35

The Gas Crisis

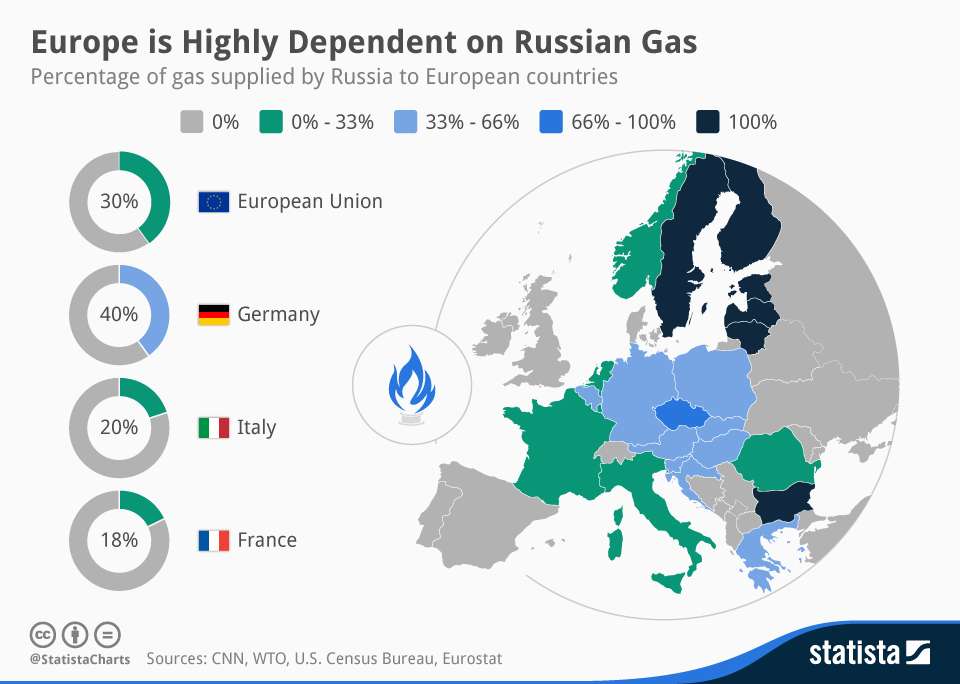

Analysts believed that the ‘Gas crisis’ in Europe was the interruption in relations between the Russian Federation and Ukraine, started in January 2006. The Russian government suddenly increases Gas prices to four folds to Ukraine. Ukrainian government consider this price hike as a deliberate move to contain Ukraine’s initiative for developing its relations with the West. While, the Russians believes that Ukraine’s pro-western approach may affect its influence in the region and damage its economy. Russia rebuffed the allegations made by Ukraine and maintained that the initiative was purely as commercial. To further increase pressure on Ukraine, Russia also reduced the flow of Gas to Ukraine. Increase in Gas prices made a wave of distress across Europe. More than 25 percent of Europe’s gas supplies come from Russia via Ukraine. To ease tension a compromise was eventually reached with Ukraine agreeing to pay about double its current price. Ukraine parliament then sacked the government of Prime Minister Yuri Yekhanurov.

Elections and its aftermath

As expected the next election stands devastating for Yushchenko’s party in 2006 elections. His opponent Viktor Yanukovych and Yulia Tymoshenko got majority of the votes, while the former defeated and later sacked by Yushchenko while he was Prime Minister. Yushchenko has to take a bitter pill and eventually to mend fences with Russia appointed his arch-rival Viktor Yanukovich as prime minister. Yanukovych has vowed to strengthen Ukraine’s ties with Russia once again. The elections held with continued unrest in Ukrainian politics. In April 2007, Yushchenko dissolved the parliament while blaming Yanukovych for consolidating power. After months of negotiations and political posturing another election held bringing back parties won in Orange Revolution. However, the political turmoil persists while Yashchenko has to face collapse of his pro-western coalition, ordering dissolution of parliament and announcing new elections.

Gazprom (the major Russian gas supplier) halted its operations in 2009. About eighty percent of Russian gas exports to Europe are pumped through Ukraine. The two countries later blamed each other for Europe’s energy crisis.

Inside Ukraine, the master of the Orange Revolution36 of 2004 Viktor Yushchenko was turned down in the first round of the Ukrainian presidential elections. Viktor Yanukovych (former Prime Minister) later won the second round in February 2010 defeating Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko by approximately three percent. International observers declared the elections to be fair while departing Premier Tymoshenko alleged that election were engineered. In March 2010, Yanukovich formed the government with Mykola Azarovas his Prime Minister. He made a public apology for his previous behavior and promised a free media, transparency in government affairs and active apposition to west.

Though after elections Yanukovych exposed prejudice for opponents by reopening investigations against several opposition members. In June 2011, Former Premier Tymoshenko was arrested on charges of signing a controversial gas deal in 2009 with Russia, resulted in gas crisis across Europe. Convicted in October 2011, Tymoshenko sentenced for seven years in jail.

Political vendetta lasts with arrests of other political leader to gain more control on Ukrainian politics, Yanukovych despite his commitment to avoid past mistakes again becomes a frontline aggressor. Dozens of his political opponents were arrested and jailed during that period.

Language Bill37

On 3 July 2012, Parliament passed a bill that endorsed Ukrainian as the country’s national language. The bill also allowed local governments to give official status to Russian with other languages. Opposition resisted the new bill with conviction that giving more control to Russian language will further distance Ukraine from EU.

The 2012 Elections and EU controversy

In 2012 elections, President Yanukovych’s ‘Party of Regions’38 claimed victory in parliamentary elections, with an estimated 33 percent of the vote. The Fatherland party, the party of jailed ex-Prime Minister Tymoshenko, came in second with 24 percent.

Under Russian influence President Yanukovych backed out from trade agreement with Europe to be signed in November 2013. To make things worse Yanukovych also refused European Union’s (EU) demand to release former Prime Minister Tymoshenko from prison. A huge protest was staged against Yanukovich in Kiev for infuriating EU, where the ordinary Ukrainians were anticipating a more promising economic and democratic future. Police responded aggressively to the protests with baton charge and heavy shelling, dispersed the crowd at the Independence Square. The protest continued with outcome of major government buildings i.e. City Hall, Trade Union Building, Independence Park came under their control while blocking the cabinet of ministers and marched further to seize the parliament building. There only demand was Yanukovych’s resignation. Yanukovych tried all efforts to overcome these protest but failed, later had to accept protestors demand and promised to resume dialogue with EU.

Instead of resuming dialogue with EU, he gained more concessions from Russia as loan of US$ 15 billion and some reduction in oil prices. His government reiterated that that the aid may prevent country from bankruptcy and provide economic stability. Ukrainian economist refuted Yanukovych claims, maintaining that unless Ukraine increases revenue and cut budget spending there are rare chances that its economy would be balanced with such loans and concessions, Ukraine was under deep financial crisis during that period.

The situation get worse in January 2014, when parliament passes a bill that outlawed protestors. The protests turned violent, five of the protestors killed in clashes with the police. Yanukovych turned to his opponents again for negotiations which resulted in threats. He later offered to install opposition leader Arseniy Yatsenyuk as prime minister. Yatsenyuk heads the Fatherland Party, which is also the party of jailed former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko. Yanukovych also offered the post of vice prime minister to another opposition leader, Vitaly Klitschko, a popular former boxer. Both refused, with possible fear that their acceptance may endorse Yanukovych’s rule.

On 28 January, the president retreated the ban on protests. Prime Minister Nikolai Azarov and his cabinet resigned the same day. Yanukovych named Serhiy Arbuzov as the interim Prime Minister. In reaction to these sudden developments and uncertainties, Vladimir Putin suspended the financial assistance package for Ukraine with some reservations on the new leadership.39

On 20 February 2014, the protesters tried to reclaim Independence Square (a central plaza) in Kiev that police had taken over few days back. More than 100 people were killed and other hundreds were wounded. On 21 February, the clashes were ended, EU officials intervened and convince President Yanukovych to hold election by the year end. President Yanukovych signed the agreement under opposition’s pressure to avoid any early resignation. Russia however, refused to endorse the deal. After this agreement, Parliament passed a series of measures that further weakened Yanukovych. The parliament also voted to acquit former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko permitting her to contest for next election. The constitutional amendments of 2008 were also withdrawn.40

The opposition refused to accept the deal and continued protests. On 22 February, Yanukovych was made to leave the capital and an interim setup was installed in Ukraine. The parliament endorsed Oleksandr Turchynov (speaker of the Ukrainian parliament) as an interim President and Arsen Avakov was appointed as interior minister in the interim setup. The interior ministry oversees the police. On 24 February Avakov issued an arrest warrant for Yanukovych citing the deaths of civilians during the protests. The statements widely appreciated as a hope to avert a civil war and edge toward stability.

In reaction to this, eastern Ukraine comes under attack, demonstrators suspected to be Russian supporters broke out in Simferopol, the capital of Crimea and pro-Russian region in eastern Ukraine. Masked gunmen took over several government buildings and raised the Russian flag. When asked, these gunmen refused to reveal their allegiance. Later two airports at Simferopol were attacked with no causalities; however, officials feared a separatist revolt.

The Black Sea Fleet was an important installation at Crimea than part of Ukraine, interim President Turchynov warned Russian troops not to intervene which Russians denied.

On 28 February Yanukovych reiterated to be President of Ukraine and termed his ouster as a ‘gangster coup.’ He also expresses his will that Crimea should not seek independence from Ukraine.

Advances at Crimea

On 1 March 2014, Russian president Vladimir Putin sends out troops to Crimea to protect ethnic Russians from anti-government protesters in Kiev. The Russian troops surrounded the Ukrainian military bases and within two days Crimea was in virtual control of Russia. The Russian initiative was widely condemned across the globe while President Obama termed it as “breach of international law.”41

In a press conference on 4 March, Putin denied suspicion of military conflict though he maintained that Russia ‘reserves the right to use all means at its disposal to protect’ Russian citizens and ethnic Russians in the region.42 At the same time critical juncture Russia also test-fired a nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missile, but said it was scheduled before the turmoil began and was not intended to exert any pressure or whatsoever.

On 25 March, Oleksandr Turchynov, Ukraine’s acting president, orders Ukrainian troops to withdraw from Crimea after formal Russia annexation. Turchynov told Ukrainian parliament that troops and their families were called back from Crimea and now be relocated to the mainland. Russia’s military chief of staff says that the Russian Army has full control of all military bases and ships in Crimea. Following the turmoil in Crimea, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announces $14 – $18 billion immediate financial assistance for Ukraine. Meanwhile, UN General Assembly approved a resolution declaring Russian annexation of Crimea as illegal. Ukraine’s ousted president, Viktor Yanukovych, calls for a referendum on Crimean status as ‘within Ukraine.’

On 29 March, Ukraine’s presidential race begins between former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko and a Billionaire Petro Poroshenko. Memorial services were held across Ukraine for Ukrainian killed at the Kiev’s Independent Square.

US Secretary of State John Kerry met with the Russian counterpart to convince him for a meaningful dialogue with Ukraine on the crisis. As a result of which on 31 March, Russian troops were partly withdrawn from Ukrainian border.

Senator Kerry also paid a visit to Ukraine to express his solidarity and pledged US $ 1 billion in aid and loans to Ukraine. John Kerry reprimanded Russian military intervention in Crimea. In other reactions future G-8 summit was also boycotted by other member states to be hosted in Russia later in 2004. They warn Moscow it faces damaging economic sanctions if President Putin takes further action to destabilize Ukraine following the seizure of Crimea.

Conclusion

There was a general perception that the Russians articulated the political development in Ukraine and its adjoining countries after the collapse of Great Soviet Union. Primarily, total dependency of Ukraine and oblasts on Russian neither leave its control on these states nor its superiority. Russia also understand its supremacy and dependency of energy sector in Europe.

Analysts maintained that,

“With the tumult in Ukraine continuing, there been lot of talk about the U.S.’s major lever in the fight against Vladimir Putin’s Russia: petro politics. Usually, its emerging powers – Russia, Iran and Nigeria – that use the spoils of oil and gas to bolster their influence. Consider that Germany, the world’s fourth largest economy, depends on Russia for about 40 percent of its energy, and Western Europe as a whole gets a third from it. It’s not hard to see why Europe hasn’t been eager to go along with trade sanctions against Russia in the past (or now). No European leader wants to risk an energy shortfall or peak prices in the middle of a cold winter.”43

The exit polls in Crimea suggested that 93 percent sought to join Russian union, inspite a world-wide condemnation of the referendum in Crimea.44 International observers view the Ukraine crisis not only as Russian influence in its former republics though it has been a test of Russian might also. Raluca Csernatoni believes that,

“Russia’s revisionism in the former Soviet Bloc is a bitter reminder of Cold-War tactics redolent of old regional standoffs and conflicts. Russia has succeeded to challenge the geopolitical status-quo in the Black Sea region and now the regional balance of power needs to be reconfigured. The developments in Crimea have tipped the balance in favor of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Worries that Putin will not stop with the Crimean Peninsula are real in the eastern periphery, with Poland, Romania, and the Baltic States voicing increased concern due to both military and economic potential repercussions in the region.”45

Besides these facts the dependency of Europe on Russian oil and so as its revenue for Russia were correlated for long. Adding to this

.. that makes European sanctions against the Kremlin a double-edged sword. The EU could cut Russia off from European financial markets or prohibit European firms from doing business in Russia, but Putin could respond by cutting off natural gas and oil exports to the EU. This would entail mutually assured economic destruction. The resulting energy shortage would likely send the EU into a recession. The same would happen in Russia, where firms would lose access to the liquid foreign financial markets and the Kremlin would find a major hole in its budget.”46

Therefore, the problem is not of the oil crisis and it’s pricing only in Europe. The global oil market would be wedged, if the crisis deepens with any shortage of oil in Europe. That could possibly shivered the oil prices across the globe. Observers maintained that for the United States, the position is depressing as well. The US is not dependent upon Russia for its energy resources but the oil prices were established in the global market. If Europe faces any energy shortage, the price of crude oil could spear and generate an economic crisis in US also.47

“The US can’t save Europe when it comes to energy. And it can’t impose truly effective sanctions without Europe’s cooperation. Thing is, it probably won’t have to. Putin’s petro state will eventually implode all by itself.”48

At present the west is more concerned about the economic repercussions than the territorial subject. Its time when the world economy specifically in US took a superficial flight, where is Europe is already affected and divided on Ukraine. The eastern European countries have their own worries of Russian possible advancement towards them. Putin had taken a rigorous stand on the issue and resolute not to compromise on Ukraine and Crimea. Moscow sees no harm in gaining back Crimea or may be Ukraine. Through Ukraine the Russians are trying to play a hard ball game for its revival in global politics and economy and to an extent they succeeded.

End Notes

1Barry Buzan and George Lawson, ‘Capitalism and emergent world order,’ International Affairs: Chatham House, Vol. 90 No. 1, January 2014, p. 71.

2Displacement may be defined as human migration or relocation after the fall of the Soviet Union.

3Aurel Braun, ‘All Quiet on the Russian Front? Russia, Its Neighbors, and the Russian Diaspora,’ The New European Diasporas: National Minorities and conflict in Eastern Europe, Michael Mandelbaum (ed.), New York: The Council on Foreign Relations, 1997, p. 81

4Ibid.

5Boris Yeltsin was the first elected president of the Russian Federation.

6Itar-Tass, 12 July 1996, this despite Article 13 of the Russian federation, which explicitly forbids the adoption if a ‘state ideology.’ Konstitutsiya, 1993; see also George Breslauer and Catherine Dale, “Boris Yeltsin and the Invention of the Russian State,” Post-Soviet Affairs 13, no. 4 (1997): 303-32

7Aurel Braun, op.cit, ref 1, p. 82

8Pereyaslav Agreement, Pereyaslav also spelled Perejas Law, (18 January 1654), act undertaken by the rada (council) of the Cossack army in Ukraine to submit Ukraine to Russian rule, and the acceptance of this act by emissaries of the Russian tsar Alexis; the agreement precipitated a war between Poland and Russia (1654–67). For further details see, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/451403/Pereyaslav-Agreement

9The Russian Revolution is the collective term for a series of revolutions in Russia in 1917, which destroyed the Tsarist autocracy and led to the creation of the Soviet Union. For further details see, https://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/Russian_Revolution_(1917).html

10In November 1927, Joseph Stalin launched his “revolution from above” by setting two extraordinary goals for Soviet domestic policy: rapid industrialization and collectivization of agriculture. His aims were to erase all traces of the capitalism that had entered under the New Economic Policy and to transform the Soviet Union as quickly as possible, without regard to cost, into an industrialized and completely socialist state.

11Ibid.

12Russophones is a terminology used for Russian speaking community after breakup of Russia

13Leonid Kuchma was the second elected President (1994 – 2005) of the Ukraine in, after the breakup of Soviet Union

14Samuel p. Huntington, ‘The Clash of Civilization,’ Foreign Affairs (Summer 1992): p. 22-48, Huntington has contended that there is a fault line dividing the civilizations within Ukraine itself, which separates Catholic western Ukraine from Orthodox eastern Ukraine,

15Andrew Wilson, ‘Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990’s: A Minority Faith,’ (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997)

16Ukraine was than part of the Soviet Republic and had disastrous effect on its economy and people.

17The communist party gained 123 seats, their potential allies, the Socialist and the progressive Socialist parties, together gained 48 seats, Russia Today, 2 April 1998.

18The doctrine introduces a new component in Russian foreign policy. This is the concept of peacekeeping and idea becomes popular in the west following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Yuli Vorontsov, permanent Russian member at the United Nations announces on 19 November 1993, that Russia is to become peacekeeper in the CIS, which it claims as its ‘sphere of influence’ Russia had tried to obtain the UN’s approval of its ‘peacekeeping’ obligation, but has not succeed in making an official UN position. [(Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States: Documents, Data, and Analysis edited by Zbigniew Brzezinski, Paige Sullivan, Center for Strategic and International Studies) (Washington, D.C.).

19The Black Sea Fleet was one of the Soviet Union’s three principal fleets, Moscow argued that Russian Federation was entitled to the entire fleet following the breakup of the Soviet Union; Kiev sought an even split. An eventual compromise saw Russia hold on to the most important warships.

20Yaroslav Bilinsky, “Ukraine, Russia and the West: An Insecure Security Triangle,” Problems of Post-Communism (January/ February 1997): 29-30.

21Paul D’ Anieri, “Dilemmas of Interdependence: Autonomy, Prosperity and Sovereignty in Ukraine’s Russia Policy,” Problems of Post-Communism (January/ February 1997): 16-25

22On Russia’s initiative, the draft treaty was supplemented with a provision that both countries, as friendly powers, would base their mutual relations on strategic partnership and cooperation. Both sides pledged to refrain from any actions that were harmful to the interests of the other side, nor to use their territories in such a way that could be detrimental to each other’s security. The document emphasized the need for a common economic space between the two countries.

23Aurel Braun, op.cit. p. 102

24Aurel Braun, op.cit. p. 103

25http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NATO

26Aurel Braun, op.cit. p. 133.

27Ibid.

28Aurel Braun, op.cit. p. 134

29Aurel Braun, ‘The Russian Factor,’ in Braun and Barany, eds. Dilemmas of Transition, pp. 273 – 300.

30Aurel Braun, ref. 5, p. 136.

31In a speech on the 200th anniversary of Gorchakov’s birth published in the Russian foreign policy journal “International Affairs,” Primakov notes that Gorchakov was able to rebuild Russia’s power and influence after its defeat in the Crimean War with Great Britain in 1856. Primakov concludes, Moscow must do everything it can to bring “the states formed on the territory of the former Soviet Union” closer together through economic integration and “the creation of a single economic area.” For further details see, Paul Goble, ‘Russia: Analysis from Washington – Primakov Nineteenth Century Model,’ 9 August 1998, http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1089195.html

32Aurel Braun, op.cit. p. 136.

33Barry Buzan, ‘A world order without superpowers: decentered globalism,’ International Relations, Vol. 25: January2011, pp. 1 – 23

34Barry Buzan and George Lawson, op.cit. p. 72

35Aurel Braun, op.cit. p. 143

36The Orange Revolution was a series of protests and political events that took place in Ukraine from late November 2004 to January 2005, in the immediate aftermath of the run-off vote of the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election which was claimed to be marred by massive corruption, voter intimidation and direct electoral fraud. Kiev was the focal point of the movement’s campaign of civil resistance, with thousands of protesters demonstrating daily. Nationwide, the democratic revolution was highlighted by a series of acts of civil disobedience, sit-ins, and general strikes organized by the opposition movement. For further details see, Adrian Karatnycky, “Ukraine’s Orange Revolution,” Foreign Affairs, Council on Foreign Relations, March-April 2005 (www.foreignaffairs.com)

37On August 8, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych signed a new law, “On the principles of language politics,” that allows cities and regions to pass legislation that would give Russian (or any other minority tongue) the status of an official language if 10 percent or more of the population of that region speaks it as a native tongue. For details and analysis see, Steven Pifer and Hannah Thoburn | 21 August 2012, http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2012/08/21-ukraine-language-pifer-thoburn

38The Party of Regions is a Russophone political party of Ukraine created on 26 October 1997 just prior to the 1998 Ukrainian parliamentary elections under the name of ‘Party of Regional Revival of Ukraine’ and led by Volodymyr Rybak. The party contains different political groups with diverging ideological outlooks. The party was reformed later in 2001. According to the party’s leadership in 2002, from the creation of the party to the end of 2001 the number of members jumped from 30,000 to 500,000. The party claims to ideologically defend and uphold the rights of ethnic Russians and speakers of the Russian language in Ukraine. It originally supported President Leonid Kuchma and joined the pro-government for United Ukraine alliance during the parliamentary elections on 30 March 2002.

39Ibid.

40http://www.independent.ie/world-news/timeline-how-the-crisis-in-ukrain

41Ibid.

42Ukraine: Maps, History, Geography… etc. op.cit.

43Rana Foroohar, “Putin has Already Lost: Russia Economy can’t sustain its leader’s ambitions,” Times, Vol. 183, No. 11, 24 March 2014

44Ben Brown, Crimea exit poll: About 93% back Russia union, 16 March 2014, BBC Online, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26598832

45Raluca Csernatoni, ‘From Cold-War zero-sum to win-win scenarios between Russia and the EU – The EU emergency summit takes a soft-line on Russia,’ ISIS Europe Blog, http://isiseurope.wordpress.com/2014/03/07/from-cold-war-zero-sum-to-win-win-scenarios-between-russia-and-the-eu-the-eu-emergency-summit-takes-a-soft-line-on-russia/

46Dany Vinik, “The Crisis in Ukraine could blow up the Global Economy,” 24 March 2014, New Republic, http://www.newrepublic.com/article/117139/sanctions-against-russia-could-cause-global-recession-ukraine

47Ibid.

48Rana Foroohar, op.cit.