We cannot afford to confine Army appointments to persons who have excited no hostile comment in their careers …. This is a time to try men of force and vision and not to be exclusively confined to those who are judged thoroughly safe by conventional standards’. Prime Minister Winston Churchill to Sir John Dill, Chief of Imperial General Staff, 1940.

In 1947, India was partitioned into two states; India and Pakistan when British decided to leave India. All assets including Indian army were divided between two states. It is to the credit of generations of fine and upright British officers for laying the foundation and subsequent growth of a professional army that was inherited by successor states. A small number of Indian officers were commissioned in 1920s and 1930s. Second World War required rapid expansion of Indian officer corps and large number of Indians were commissioned as officers. At the time of partition in 1947, only a very small number of Indian officers were holding the rank of Brigadier. India and Pakistan decided to retain senior British officers as an interim measure while native officers were groomed for senior positions.

In India, General Robert Lockhart (commissioned in 51st Sikh; now 3 Frontier Force of Pakistan army) was appointed first C-in-C. He relinquished charge in January 1948 on grounds of ill health and was succeeded by Lieutenant General Francis Robert Roy Bucher (commissioned in 55th Coke’s Rifles; now 7 Frontier Force of Pakistan army. He later changed to 32nd Lancers that was amalgamated with 31st Lancers in 1922 to form 13th Lancers; now an elite cavalry regiment of Pakistan army). Near the end of 1948, it was decided to appoint an Indian C-in-C to complete the nationalization process.

Following incident has been narrated by many although no original source of this information has been cited. The story goes that after getting freedom, a meeting was organized to select the first Indian C-in-C. Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru was heading that meeting attended by political leaders and senior army officers. Nehru said that, “I think we should appoint a British officer as a General of Indian Army as we don’t have enough experience.” Everybody supported Nehru because if the Prime Minister was suggesting something, how can they not agree? But one of the army officers abruptly said, “I have a point, sir.” Nehru said, “Yes, gentleman. You are free to speak.” He said ,”You see, sir, we don’t have enough experience to lead a nation too, so shouldn’t we appoint a British person as first Prime Minister of India.” The meeting hall suddenly went quiet. Then, Nehru said, “Are you ready to be the first General of Indian Army?” He got a golden chance to accept the offer but he refused and said, “Sir, we have a very talented army officer, my senior, Lt. General Cariappa, who is the most deserving among us.” The army officer who raised his voice against the Prime Minister was Lieutenant General Nathu Singh Rathore. Lieutenant General S. L. Menezes narrates a similar story but instead of Nathu Singh gives the name of Lieutenant General Rajendra Sinhji. Menezes states that interim government decided to appoint Rajendra Sinhji as first native C-in-C. When this was communicated to Rajendra Sinhji, he advised that decision should be based on seniority thus suggesting Cariappa’s name. However, Menezes does not give the source of this information.1

This incident confuses two issues; one of retention of British officers and second selection of first Indian C-in-C. The meeting where Nathu expressed his views in the presence of Nehru was not related to the selection of first Indian C-in-C but retention of British officers. Major General V. K. Singh was given Nathu’s private papers by Nathu’s son Vice Admiral Ranvijay and son-in law Colonel Guman Singh (he has the distinction of commanding his father-in-law’s battalion 1/7 Rajput) for his book. Nehru invited senior army officers immediately after independence to ascertain their views about retention of British officers. Nathu replied that Indian officers were capable of holding senior appointments in the armed forces and retorted that ‘as for experience, if I may ask you, Sir, what experience you have to hold the post of Prime Minister?’2

The issue of selection of first Indian C-in-C was first raised in late 1946 during interim government. It was at that time that the name of Nathu was floated as first Indian C-in-C and the evidence is a letter of then Defence Minister in the interim government Sardar Baldev Singh. Baldev’s letter to Nathu dated November 22, 1946 very clearly states that ‘You have been selected and earmarked to be first C-in-C of India’. Baldev elaborated in this letter that this decision was reached ‘in consultation with other political parties including Muslim League and on recommendation of Auchinleck and approval of Governor General’.3 There is no evidence that issue of selection of C-in-C was discussed in a large meeting. Probably, senior officers were sounded individually with verbal communication rather than open discussion at a formal meeting.

Thakur Nathu Singh Rathore was commissioned in 1/7 Rajput (he later commanded 9/7 Rajput as well as his parent battalion 1/7 Rajput). Commander Hirak Nag who was friend of Nathu’s son Ranvijay; a naval aviator met Nathu at his home. Nathu narrated to Nag his early childhood episode. Nathu was from a high caste but not very affluent family. He was orphaned at young age. One day when he was playing with other children, the Raja of Dungarpur approached riding his horse. All children ran away but Nathu stood his ground. When Raja asked him why he didn’t run away like other children, Nathu replied that he had done no wrong therefore he need not to run away. The Raja was impressed by his candor and became Nathu’s guardian. Nathu was sent to Raja’s alma mater Mayo College at Ajmer.4 Even after Raja’s death, Nathu was supported by Raja’s heirs and were instrumental in Nathu’s military career.

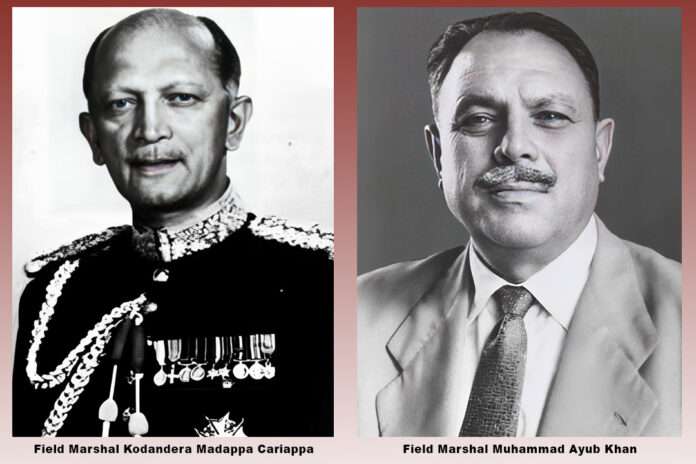

General Kodandera Madappa Cariappa (nick named Kipper) was appointed first Indian C-in-C on January 15, 1949 and retired after a four year tenure on January 14, 1953. The three army commanders at the time of Cariappa’s retirement were Lieutenant General Rajendra Sinhji (commissioned in 2nd Royal Lancers also known as Gardner’s Horse), Lieutenant General Nathu Singh and Lieutenant General S. M. Shrinagesh (Commissioned in 2/1 Madras Pioneers but on disbandment of the battalion joined 4/19 Hyderabad Regiment; now 4 Kumaon of Indian army). Rajendra Sinhji was selected as next army chief.

Nathu’s personality was such that he minced no words and at times could be quite unbearable. Political leadership especially Nehru was not very fond of him and few interactions between the two have not been congenial. Even his brother officers sometimes found Nathu unbearable. Cariappa though great admirer of Nathu found him ‘loquacious and arrogant’.5 In March 1948, Nathu was serving as General Officer Commanding (GOC) United Provinces (UP) area and when his superior Army Commander Lieutenant General Rajendra Sinhji didn’t grade him ‘outstanding’, Nathu made a representation against it and Rajendra Sinhji had to reverse his report. Nathu had also made a representation for extension of his service that was rejected. In 1951, Nathu wrote a letter to Cariappa with allegations against Adjutant General Major General Hira Lal Atal. Nathu alleged that implementation of the rule of four year tenure for army commander was malafide on part of Atal to clear the path for his own promotion. Government of India sent Nathu a letter of displeasure for aspersion on the character of a brother officer.6 These few incidences clearly show Nathu’s problems even with his own institution and brother officers. In my view, the political leadership took into consideration these traits of Nathu and decided that he may not be the best choice for C-in-C post. The second factor is related to Rajendra Sinhji. A scion of princely Jadeja family of Nawannagar, Rajendra Sinhji was an outstanding officer and had the distinction of first Indian officer to win Distinguished Service Order (DSO). He was a top contender in 1949 for the C-in-C slot and many officers favored him. Selection of Cariappa as first Indian C-in-C caused some disappointment among Rajendra Sinhji’s admirers. Cariappa probably recommended Rajendra Sinhji to succeed him to prevent dissension among senior officers.

Nathu was a bitter and angry man at the end and felt that he had been cheated and should have been selected as army chief after Cariappa. He also blamed Cariappa for not standing up for the interests of armed forces. Major General Surjit Singh met Nathu in 1987. Surjit was then Colonel in the Pay Cell and was ordered by Adjutant General to meet Nathu and brief him on the effect of the Fourth Pay Commission on the pension of the King Commissioned Indian Officers (KCIOs). Nathu was at Military Hospital in Delhi and Surjit spent two hours with him. According to Surjit, Nathu was an angry old man and what he said about Field Marshal Cariappa is unprintable. Nathu blamed Cariappa for not standing up to politicians and bureaucrats when order of precedence of army officers was downgraded. Nathu told Surjit that ‘the history of the Indian Army would have been different if the first COAS was someone else.’7 Nathu had clashed with British officers throughout his career and had nationalist outlook but in the end he admitted the fair play of British. Comparing British with Indian officers he said, ‘If you take the best of them, we have never produced anyone quite like them. I have not known a British officer who placed his own interests before his country’s and I have hardly known any Indian officer who did not’.8

In case of Pakistan, General Frank Messervy (he was commissioned in Hodson Horse and later commanded 13th Lancers) was appointed first C-in-C on August 15, 1947. He retired on February 1948 and succeeded by his Chief of Staff (COS) General Douglas Gracey (commissioned in Ist King George’s Own Gurkha Rifles and later commanded 2/3rd Gurkha Rifles). At the time of independence, Pakistan had only two Brigadiers; Muhammad Akbar Khan Rangroot and Nawabzada Agha Muhammad Raza (his name is written NAM Raza while some documents show it AMN Raza; Agha Muhammad Naeem Raza) and a handful of Colonels and Lieutenant Colonels. Pakistan retained a number of British officers at senior positions while rapid promotions were given to a number of Pakistani officers. Akbar Khan was promoted Major General on August 15, 1947 and given command of 8th Division in Karachi. Akbar had spent most of his career in Army Service Corps (ASC) and had no previous command, staff or instructional experience. Despite being the senior most officer with Pakistan Army number of 1 (PA-1), he was not considered by either British or Pakistanis to be suitable for C-in-C position. One story suggests that when he was offered the post of first native C-in-C, he declined stating that he was not qualified for the post. However, there is no authentic source for this story. Akbar retired at the rank of Major General in 1950.

Akbar’s younger brother Muhammad Iftikhar Khan (commissioned in 7th Light Cavalry) jumped two ranks soon after partition to become Major General and given command of 10th Division in Lahore on January 01, 1948. He was considered a suitable candidate to be the first Pakistani C-in-C both by his British superior officers and Pakistani decision makers. In 1949, it was decided to send him for Imperial Defence College (IDC) course to prepare him for his coming top assignment. Unfortunately, in December 1949, he died in a plane crash in Jungshahi near Karachi.9 Another bright officer and then Director Military Operation (DMO) Brigadier Sher Khan also perished in this crash. A year later, when the time came for selection of first Pakistani C-in-C, two senior most officers Akbar and Raza had some handicaps. Akbar had spent long career in ASC and Raza had not commanded a division. Ayub Khan had served as General Officer Commanding (GOC) 14th Division in East Pakistan and Adjutant General (AG) and was chosen as first Pakistani C-in-C. Then Defence Secretary Iskandar Mirza (later Governor General and President) was probably instrumental in selection of Ayub for the top slot.

Ayub Khan was sent to command 14th Division in East Pakistan with the local rank of Major General. This could have caused confusion in terms of seniority and General Gracey sent a note to Military Secretary stating that when Ayub is promoted to Major General rank, this will be antedated to the date of his local Major General rank starting January 08, 1948. Gracey went ahead to clarify the seniority list putting Ayub ‘NEXT below Maj. General Iftikhar Khan, and next above Major General Nasir Ali Khan’.10 The command of 14th Division needs some elaboration. At the time of partition, the command in East Pakistan was designated East Pakistan Army. Ironically, this grand title was given to a formation that consisted of a single infantry battalion; 8/12 Frontier Force Regiment. When Ayub assumed command in January 1948, it was called East Pakistan Sub Area and consisted of only two infantry battalions. Command of 14th Division played a major role in the decision of Ayub’s appointment as first C-in-C although technically Ayub’s command consisted of only two infantry battalions.

Syed Wajahat Hussain (later Major General) served as ADC to General Gracey in 1947-48 at the rank of Lieutenant. In 1956, he visited England and stayed with General Gracey. Wajahat states that Gracey told him that after the death of Iftikhar in plane crash, the choice of C-in-C was narrowed down to Ayub, Raza and Nasir Ali Khan. According to Gracey, Ayub was picked because of his command experience compared to Raza and Nasir although Gracey was worried about Ayub’s political ambitions.11 Raza was commissioned in 1/7 Rajput and later commanded 6/7 Rajput and 18/7 Rajput battalions.12 Raza was the first Pakistani AG. Nasir was also commissioned in 7th Rajput Regiment and commanded 9/7 Rajput. He was the first Pakistani Military Secretary (MS), Quarter Master General (QMG) and Chief of Staff (COS) of Pakistan army. Rajput regiment can be truly proud that two senior Indian (Cariappa and Nathu Singh) and two senior Pakistani generals (Raza and Nasir) considered for the top slot as first C-in-Cs belonged to this elite regiment.

Ayub’s appointment as first C-in-C has been criticized by many with the hindsight. This criticism is invariably in the context of Ayub’s coup and long tenure as President with the assumption that another army chief was not likely to launch the coup. In the argument against Ayub’s professionalism a bad report is cited which is probably ‘tactical timidity’ during Second World War in 1944-45 by his commander Major General Thomas Wynford ‘Pete’ Rees (Served with 1/3 Madras during First World War, long stint with 5/6 Rajputana Rifles and commanded 3/6 Rajputana Rifles). Rees was commanding 19th Division in Burma. Ayub was serving with First Assam Regiment as second in command (2IC) at the rank of Major. First Assam was a divisional support unit under direct command of Rees. On January 10, 1945, Commanding Officer (CO) of First Assam Lieutenant Colonel W.F. Brown was killed and Ayub Khan assumed command. Ayub was removed from the command by Rees when Ayub suggested that battalion was not fit for the assigned task. Rees considered this as tactical timidity and removed Ayub from command. On March 07 (some accounts give the date of March 15), 1945 Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Parsons took command from Ayub. Parsons was originally from 5/6th Gurkha Rifles and had served with First Assam in the past. Ayub stayed in the tent of Risaldar/Honorary Captain Ashraf Khan of Hazara until his departure to India on April 18.13

Normally, during war if CO is killed in action 2IC takes command of the battalion immediately until a new commander is posted. It is possible that Ayub was appointed acting CO with temporary rank of Lieutenant Colonel and when new commander was appointed about two months later, he reverted back to Major rank. Ayub survived the bad report of Rees and later re-raised and commanded his parent battalion 1/14 Punjab (now 5 Punjab of Pakistan Army). Some suggest that Ayub had this negative report removed from his file when he became C-in-C. Shuja Nawaz who was given access to Ayub’s file for his encyclopedic work on Pakistan army does not recall seeing Rees’s report in the file.14

Ayub’s encounter with Rees and his statement that battalion was not fit for war can be interpreted in two ways. Admirers of Ayub will interpret this as an expected response from an upright officer to present the true picture even if unpalatable while critics of Ayub will interpret this as an example of ‘cowardness’. Incidentally, Rees’s own fortunes during the war were not that different. In North Africa, as 10th Division commander, Rees refused a task assigned by his superior XIII Corps Commander Lieutenant General William Gott on the grounds that his division was not fit for the task. Gott considered this act as lack of resolution and sacked him. Rees was demoted to Brigadier rank and sent back to Delhi as President of the Army Establishments Committee. Rees was rehabilitated when he got the command of 19th Division after its temporary commander was sacked. Rees then led his division with élan during the war in Burma theatre. Rees was a highly decorated officer winning DSO and bar and Military Cross.

Contrary to popular belief, selection of army chief is essentially a political appointment, regardless of the form of government. Military commander is chosen by the head of the government whether King, military ruler, President or Prime Minister. In addition to professional competence, several other factors such as personality, ability to work with his fellow officers as well as head of the government are considered during the selection process. At the time of partition, senior officers of India and Pakistan were of different shades. One group was thoroughly Anglicized. These officers were from traditional aristocracy as well as princely families, educated at British run schools, some even in England, fully comfortable in British company and scrupulously apolitical. Cariappa, Rajindra Sinhji, Srinagesh, Thimmaya and J N Chaudhri, in India and NAM Raza in Pakistan were representatives of this group. The second group consisted of officers belonging to rural class that had flourished under British rule either from recruitment in the army or agriculture. These officers were culturally conservative and not thoroughly Anglicized. Nathu Singh in India and Ayub Khan are representatives of this group. Both groups were firmly attached to the established order and were not considered to harbor any revolutionary ideas. The fear of coup d’état had not yet taken hold among political leadership at that early stage.

A very small number of officers were influenced by political consciousness due to turbulent political times of 1945-47. Some only expressed nationalist views while others had some contacts with politicians. Nathu Singh and J.S. Dhillon (later Lieutenant General) in India and Akbar Khan (1951 conspiracy case fame) in Pakistan were not hesitant to express their nationalistic views. These officers were thoroughly professional and had an excellent service record therefore their nationalistic views didn’t hinder their promotion. On the other hand, officers like B. M. Kaul were not well regarded professionally but had developed direct contacts with politicians. Their brother officers accused them of using their political contacts to advance their careers and secure senior positions which they could not attain through professional competence.

Akbar Khan (commissioned in 13 Frontier Force Rifles) was a professional officer, well respected by his peers and one of handful of Indian officers who won Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in Second World War. He could have easily become C-in-C in due time on his own merits but he was more ambitious and had a temper problem. In addition, he was influenced by his urban wife Nasim Akbar. Nasim was even more ambitious than her husband and she was instrumental in introducing Akbar to nascent and small leftist and Communist intelligentsia of Pakistan.

Air Marshal Asghar Khan narrates an incident that happened on Pakistan’s Independence Day on August 14, 1947. Country’s founder and Governor General Muhammad Ali Jinnah gave a reception on that day. A group of about dozen officers of armed forces were also invited. Akbar then Lieutenant Colonel suggested to Asghar that they should talk to Jinnah. Akbar told Jinnah that officers have hoped that in new country ‘our genius will be allowed to flower’ and that he was disappointed that ‘higher posts in the armed forces had been given to British officers who still controlled our destiny’. Jinnah pointing his finger reprimanded Akbar stating that ‘Never forget that you are the servants of the state. You do not make policy. It is we, the people’s representatives, who decide how the country is to be run. Your job is only to obey the decisions of your civilian masters’.15 Akbar’s views were well known on this subject and even before partition he had testified before Armed Forces Nationalization Committee and advocated immediate nationalization of armed forces.16 However, Akbar’s admirers and detractors will interpret these events differently. Akbar’s clandestine involvement out of army’s normal chain of command in 1947-48 Kashmir war and later disappointment with politicians set in motion a chain of events that resulted in what is known as Rawalpindi Conspiracy case. In 1951, Akbar then serving as Chief of General Staff (CGS) was arrested along with several other officers on charges of conspiring to overthrow civilian government. He was tried, convicted and sentenced to jail term.

Indian and Pakistani political leadership had to choose among the available lot of relatively small number of senior officers. All these officers were average and each with some strengths and weaknesses. They preferred thoroughly apolitical officers for senior positions and it was in this context that Cariappa and Ayub were chosen as first native C-in-Cs in their respective countries. It is always more than one officer that is capable to assume the highest position in the army. This does not mean that those who don’t reach the highest post are less competent. A true professional officer will always perform to the best of his abilities at any position and work though it is his last post. However, such officers are a very rare commodity and most are fallible human beings. Personal ambition is an essential element in the quest for excellence and soldiers are no exception. The fine line between personal and institutional interests is sometimes blurred and becomes the basis for different perspectives.

‘Humility must always be the portion of any man who receives acclaim earned in the blood of his followers and the sacrifices of his friends.’ General Dwight Eisenhower

Notes

1Lt. General S. L. Menezes. Fidelity and Honour (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 448

2Major General V. K. Singh. Leadership in the Indian Amy: Biographies of Twelve Soldiers (New Delhi: Sage Publishers, 2005), p. 78

3Singh. Leadership in the Indian Army, p. 68

4http://reportmysignal.blogspot.com/2010/09/gen-nathu-singh-afspa-readers-views.html)

5Singh. Leadership in the Indian Army, p. 79

6Singh. Leadership in the Indian Army, p. 79-80

7http://reportmysignal.blogspot.com/2010/09/lt-gen-nathu-singh-courage-and-candour.html)

8Singh. Leadership in the Indian Army, p. 80

9Major General ® Shaukat Raza. The Pakistan Army 1947-49 (Lahore: Services Book Club, 1989), p. 183

10Shuja Nawaz. Crossed Swords: Pakistan, Its Army, and the Wars Within (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2008), p.80

11Interview of Major General ® Syed Wajahat Hussain by Major ® Agha H. Amin, Defence Journal, August 2002

12Lieutenant Colonel Mustasad Ahmad. Living Up To Heritage: The Rajputs 1947-1970 (New Delhi: Lancer Publishers, 1997), p. 9 & 15

13Lt. Colonel Mohtaram met Ayub during this time and he narrated this incident in a letter to Colonel S. G. M. Mehdi. This letter is reproduced in Air Commodore S Sajad Haider’s memoirs Flight of the Falcon: Story of a Fighter Pilot (Lahore: Vanguard Books, 2009), Appendix C

14Personal communication to author, May 2011

15M. Asghar Khan. We’ve Learnt Nothing From History: Pakistan: Politics and Military Power (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 3

16Lieutenant General B. M. Kaul. The Untold Story (New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1967), p. 82