Carl Von Clausewitz (1780-1831) is one of the thinkers of the 19th century who analysed war and its various characteristics based on his experience and the literature of the time. His book On War (published posthumously in Prussia as Vom Kriege in 1832), is considered most important single work on theory of warfare and strategy and is now being interpreted by militaries, businessmen and political scientists alike. His thoughts are considered to influence the thinking of Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke in the wars of German unification (1864, 1866, 1870-71). It is also claimed that George Patton and Dwight Eisenhower were also influenced by his concepts. His works have gained further significance on becoming part of the curriculum at United States (US) War colleges since 19781. Some critics believe the concepts and principles advanced by Clausewitz are limited to his own era as they are solely based on his experiences as a professional soldier. They believe they are relevant to the western model of a nation state and not applicable to unconventional wars; conversely, others argue his ideas are universal and remain applicable to any war. In order to address this dilemma, the literature of two authors, Simpson2 and Echevarria3 have been analysed on the relevance of Clausewitz to the conflict of 21st century.

While both authors have analysed Clausewitz for contemporary conflicts, each has used a different example. Simpson chose the coalition operations in Afghanistan whereas Echevarria discussed the war on terror against Al-Qaida. Simpson focussed on the United Kingdom (UK) forces deployment in Afghanistan’s Helmand province in 2006 as a case study and examined three cornerstones of war: the principle of polarity, the physical and perceived component of war’s outcome and strategic audiences and their relationship to the state. Echevarria expressed his views on three forms of dualism in the nature of war. He provided an interpretation of Clausewitz’s trinity of war to analyse the nature of the war on terror. Although both authors are professional soldiers,4 their ideas differ on various aspects. The ideas of each author and their differences are discussed hereafter.

The main difference between the two authors is their choice of case study and interpretation of various aspects of modern day conflicts. In Simpson’s point of view, Clausewitz’s analysis of war is flexible and does not resist change, rather it accounts for it.5 Simpson believes the traditional framework of war can work when the enemy and outcome of war against the enemy can be defined; whereas in contemporary conflict there is a compromise between these two prerequisites; hence, the function of war as a political instrument is also compromised. Thus Simpson terms conflict in Afghanistan as armed politics outside war. In Echevarria’s point of view, the globalisation is making the effects of Clausewitz’s trinity (interpreted as interaction of purpose, hostility and chance) immediate, less predictable and potentially more influential. These may not change the basic concept of war (imposing will on others), but will certainly affect the tactics and means which one might decide to use6.

Simpson considers the principle of polarity and role of the enemy is vital to define the military outcomes of the conflict. Polarity means the identification of both friend and foe to provide cognitive stability to military actions in war. He considers forces lose decisive political meaning without polarity and sometimes it is necessary to accentuate the existing polarity to give political utility to force.7 To support his argument, the Bosnian conflict of 1990s has been quoted where NATO forces were deployed to deal with humanitarian crises. However, the conduct of the Kosovo Liberation Army and Serbian forces in committing atrocities against humanity was observed to be similar by NATO forces. However, NATO was able to shape the battlefield in terms of a clear understanding of right versus wrong despite a morally complex situation. This enabled decisive action on ground. In Afghanistan, the clear polarity did not exist due to shifting loyalties among warlords. Hence, Simpson concludes that polarity is relative and parties of conflict may be drawn temporarily to suit their interests. Accordingly, it is one of the roles of strategy to define polarity in any conflict so that a military result can be defined. The concept of polarity was not discussed in Echevarria’s article. He considered the US and Al-Qaeda as two belligerents and no polarisation within each have been discussed.

Simpson’s point of view on physical and perceived component of war’s political outcome is another concept. He argues that concept of victory and defeat is unstable and perceptions can change. Thus it is the perceived quality of a war’s decision expressed as ‘strategic narrative’ of the events which matters. Hence war is a competition between strategic narratives of two belligerents and in modern day warfare it is difficult to articulate strategic narrative due complexity to define polarity.8 The concept of strategic narrative has not been mentioned by Echevarria, however, in his interpretation of Clausewitz, ‘the first and most comprehensive of strategic tasks’ is to recognise correctly the kind of war one is about to undertake or drawn into but not what he desires to be.’9 While describing the first aspect of Clausewitz’s trinity, purpose, he stated the US is using all kind of hard and soft measures to make Al-Qaeda’s ideology irrelevant. These include counter terrorism operations as well as diminishing the conditions that terrorist groups exploit for recruitment and earn sympathies of target populations. This may be considered strategic narrative in war on terror.

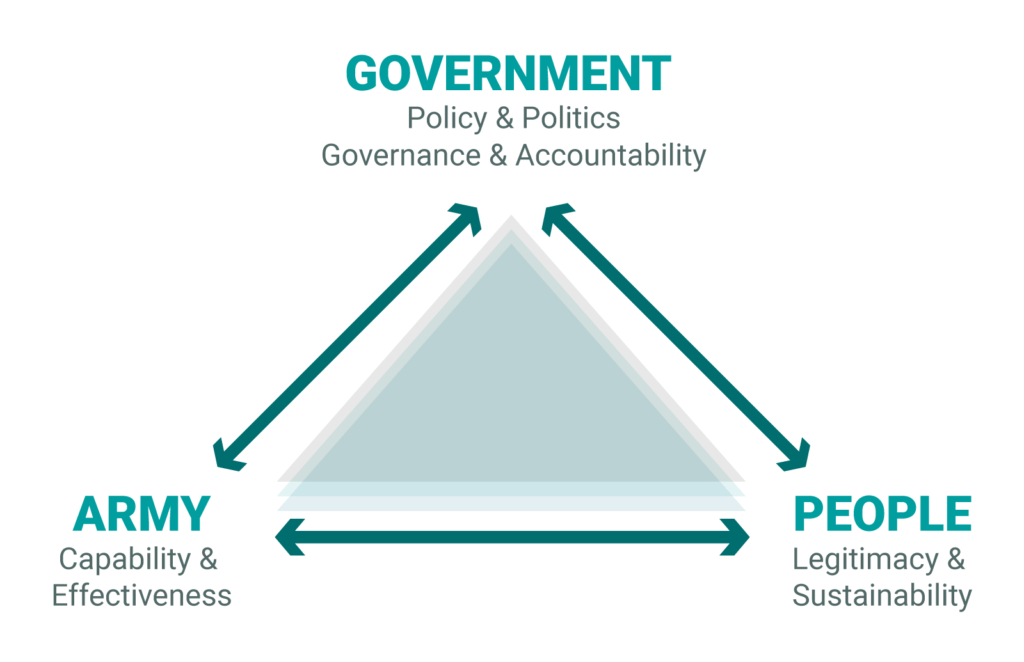

Simpson uses a new term ‘strategic audience’ that applies to a group of people whom strategy seeks to convince of its strategic narrative.10 He divides them into two categories. First is between own side and enemy whereas second is between people, government and army within each side. He considers them as the arbiters of war’s outcome and influencing their perception as the strategic objective of any campaign. So in any campaign, the unification of own strategic audience and making adversary’s strategic narrative irrelevant to his strategic audience is also an objective of any campaign. To support argument, examples of Vietnam War and Malayan Emergency have been quoted. During Vietnam War, US strategy failed to unify strategic audience on their side and considerable differences existed in perception of success between US administration, public and armed forces. So Simpson does not consider it a legitimate claim of victory. Similarly in Malayan Emergency, although British forces defeated Malayan Communist Party (MCP) in 1960, some factions of MCP did not surrender until 1989. Simpson argues although remnants of MCP did not accept defeat in 1960, but their strategic narrative was irrelevant to their strategic audience, which they had to accept in 1989. The term strategic audience is not used by Echevarria, however, he has deliberated that in the war on terror, and both Al-Qaeda and the US are using emotions and hostility to fuel their interpretation of war. While Al-Qaeda is using the Palestinian issue, atrocities in Bosnia, Chechnya, Somalia, Afghanistan and Iraq as purpose of their struggle, the US is using the issue of terrorism and violent extremism as purpose of their operation. Echevarria thinks in the war on terror, the population is being used both as a weapon and as target, physically and psychologically11. Al-Qaeda and other associated movements have turned their constituencies into an effective weapon by strong social, political and religious ties with them. These include welfare projects that are lacking in many such countries due to corrupt and inefficient public institutions. These groups of people are used to facilitate financial, logistical and information networks. These organisations also use the population as target for recruitment and other kinds of assistance. Al-Qaeda and other such movements target an adversary’s population to revenge the operations against them.

Simpson has not discussed the concept of chance and probability. Echevarria believes the growth of information technology amplified the chance and probability factor of Clausewitz’s trinity due to the availability of a large number of expert opinion and greater access to information. Despite large number of experts, root causes of extremism are not defined or agreed upon, primarily because it may be considered justifying the terrorism12. So the uncertainty exists in the fields of tactics and operations as well as in the field of policy and strategy13.

Clausewitz era was nearly 200 years ago but his legacy continues today. Based on his relevance in contemporary warfare, he is also being interpreted for other fields of study. Every new conflict is viewed through lens of On War. Review of articles of both the scholars makes it clear that although both have analysed two different conflicts of 21st century and used different parameters for analysis, both agree on relevance of Clausewitz’s theories to the conflicts of 21st century. In Simpson’s understanding of Afghanistan war, polarity is the main determinant which can simplify the interpretation of modern day conflicts. Echevarria considers that all elements of Clausewitz’s trinity exist in the War on Terror and these elements are not people, government and military rather hostility, purpose and chance. Although both authors are professional soldiers with on ground battle experience, their parameters for interpretation of the conflicts differ. Probably it is their respective organisational approach to conflicts which is depicted in their understanding of modern day conflicts.

Bibliography

Bassford, Christopher. ‘Clausewitz and His Works,’ last modified September 23, 2012.

http://www.clausewitz.com/readings/Bassford/Cworks/Works.htm.

Echevarria II, Antulio J. ‘Clausewitz and Nature of the War on Terror’, in Hew Strachan and Andreas Herberg Rothe, Clausewitz in the Twenty-First Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Simpson, Emile. War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First-Century Combat as Politics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

End Notes

1‘Clausewitz and His Works,’ last modified September 23, 2012, http://www.clausewitz.com/readings/Bassford/Cworks/Works.htm.

2Emile Simpson, War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First-Century Combat as Politics. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 41-67.

3Antulio J. Echevarria II, ‘Clausewitz and Nature of the War on Terror’, in Hew Strachan and Andreas Herberg Rothe, Clausewitz in the Twenty-First Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 196-218.

4Emile Simpson served in the British Army from 2006-12 as an infantry officer in the Royal Gurkha Rifles and Dr. Antulio J Echevarria II has over 20 years’ experience in US Army.

5Simpson, War from the Ground Up, 66.

6Echevarria, Nature of the War on Terror, 209.

7Simpson, War from the Ground Up, 56.

8Simpson, War from the Ground Up, 61.

9Echevarria, Nature of the War on Terror, 211.

10Simpson, War from the Ground Up, 62.

11Echevarria, Nature of the War on Terror, 214.

12Echevarria, Nature of the War on Terror, 216.

13Echevarria, Nature of the War on Terror, 217.