On the face of it, the answer appears to be a resounding ‘Yes’, yet the PPP which currently rules the roost in the province of Sindh vehemently opposes any such suggestion when it comes to their province, terming the demand of MQM for giving Karachi a provincial status, a diabolical plan to break up the very federation of Pakistan. Ironically the party is ambivalent, in fact tacitly agrees and supports the creation of new provinces in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. ‘Division of Sindh over our dead body’ is the rallying cry and response of young Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, the chairman of PPP to the subdivision of Sindh into two or more autonomous provinces. Given that the original four provinces of today’s Pakistan (Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan) have seen their population burgeoning and particularly in Sindh more than quadrupling, besides undergoing fundamental changes in their demography since the country gained independence in 1947, has their bifurcation into smaller and administratively more manageable independent provincial units become unavoidable – or is there any merit in the fear of the PPP that any such move is an attempt to dismember the Sindh motherland and is likely to shake the fabric of the federation. These are the aspects this article will examine.

With the increase in population and changes in demography over the past six and a half decades since independence, subdivision of existing provinces is an ongoing phenomenon the world over. Just across the border in India, there were less than a dozen provinces when it achieved independence and today it has as many as twenty-nine as a result of their division and subdivision. The province of Haryana was carved out of the territory of the Indian Punjab in 1966 while both share Chandigarh as their capital venue. The most recent example is of the state of Andhra Pradesh which has similarly been bifurcated and the new province of Telangana has come into existence just this year (2014). The proposal to further divide Uttar Pradesh (UP) – which earlier had been bifurcated into two – is currently being hotly debated.1 While this is a reality, it is also true that the creation of each new province was not without struggle, violence and even bloodshed in nearly every instance.

The provincial ruling parties in India ensconced in their capitals invariable opposed any split while those in the periphery fought to break away from the provincial power centres and this phenomenon is clearly discernable in Pakistan as well. While the Indian system has successfully managed to steamroll the opposition and carved new provinces from the existing ones, Pakistan so far has been unable to do so and continues to maintain the status quo despite the vociferous demands by the Hazarawal, Seraiki and Mohajir communities to declare Hazara, South Punjab and Karachi as new provinces in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab and Sindh respectively.

The democratic setup at the federal level under the previous PPP government had taken a very positive step of devolution of power from the centre to the provinces via the 18th Amendment but further devolution down to the local level is still not forthcoming. Under the 18th Amendment, establishing functioning Local Government (LG) system in the urban and rural centres of the country is now is the responsibility of the provinces. When put in place it would empower the people at all levels and usher in the real fruits of the democracy to the general public – unfortunately this has not been done despite it being an important part of the manifestoes of both PML (N) and PPP, which have been ruling Punjab and Sindh for over six years. The failure of the ruling cliques to do so is largely responsible for the demand of new provinces, especially in Sindh.

Sindh as a geographical entity has existed since time immemorial but when annexed by the British in 1843 during their rule in the subcontinent it was initially made a part of the Bombay (currently Mumbai) Presidency.2 It fought for and eventually achieved an independent provincial status still under the British Raj in 1935 with Karachi as its capital.3 This was the situation at the time of the country’s independence in 1947 but when Karachi was chosen as the national capital, the city in 1948 was declared a Federal Capital Territory (FCT) and was no longer a part of Sindh.4 In 1955 the rest of the province was merged with the other three provinces of the then West Pakistan under the ‘One Unit policy’, only to be undone in 1970 whereby Sindh regained its original status.5 In 1958 the national capital was shifted to Islamabad by Ayub Khan and Karachi again rejoined Sindh province as its capital city.

A cursory study of the history of Sindh reveals that its original boundaries during the periods of Raja Dahir, the Ghaznavis and even under the Mughals had extended as far north as Multan. The boundaries kept altering with the changes in the ruling regimes and the present dimensions of the province are what the British inherited when Sindh was annexed. To treat the political boundaries of the province as sacrosanct and unchangeable would be to ignore history. As far as modern Karachi, as indicated earlier from 1948 to 1958 it was separated from the province and made into a federal territory. The current proposal of making it an independent province as a part of the federation may be opposed for a whole range of factors but to term it as a betrayal of the Sindh motherland would be unfair.

The opposition to the creation of Hazara and Seraiki provinces in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab is primarily based on political considerations whereas in the case of Karachi there are economic factors and implication that must be considered before a decision is taken on making Karachi a province. To begin with, the debate on the subject should avoid the slogan that the young PPP Chairman has adopted because it would lead the entire discussion into a blind alley, much like the Kalabagh Dam controversy, where narrow parochial, jingoistic and ethnic considerations trump any rational debate on the merits and demerits of the issue. Highlighting the serious negative financial aspects on the rest of the province would be a far saner and logical approach when arguing against the proposal.

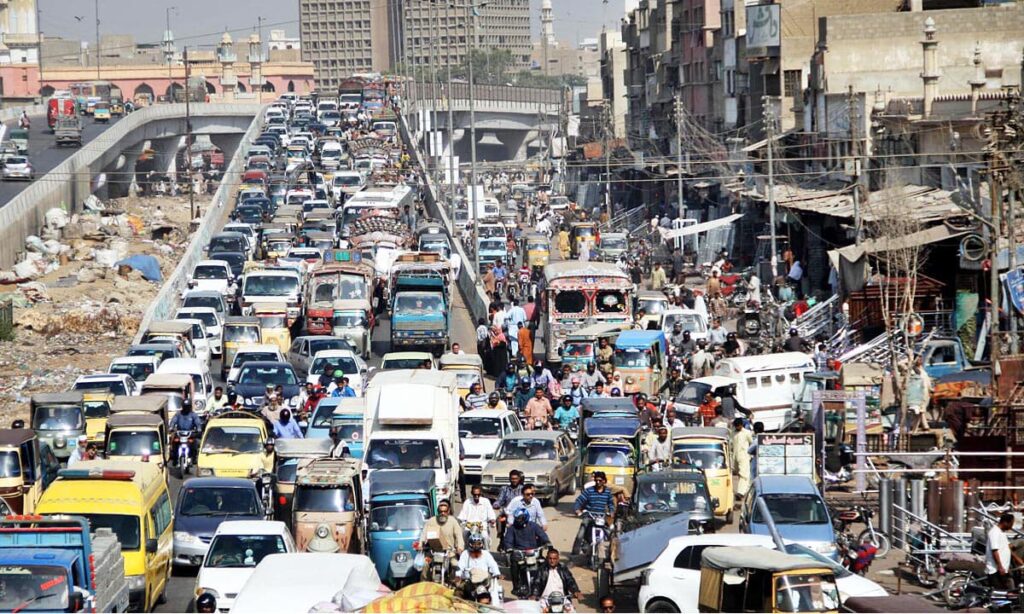

With a population of over twenty million and covering an area in excess of 3500 square kilometres, Karachi’s physical boundary is larger than sixty-one country’s worldwide and in population it outscores around two hundred other nations and dominions. In addition, the metropolis is the financial capital of the country contributing around 65% of the national revenue. Viewed in context of the province of Sindh, Karachi’s economic footprint within Sindh is overwhelming and in many socio-economic indicators Karachi’s share in the province is more than 80 percent.6 If Karachi is declared an independent province it would leave the rest of the province financially impoverished and such an imbalance by itself would lead to severe complications both at the provincial and federal levels.

Assuming the whole of Karachi becomes a province, its economy would dwarf the rest of Sindh and the imbalance would turn the current in-migration from rural Sindh to Karachi into a deluge which the city would neither be able to prevent nor cope up with under the present laws of the land. Given its size and population Karachi is actually an amalgamation of two or three cities. One could consider separating Malir/Landhi/Korangi combine along with North Karachi from the new province and make them a part of the rest of Sindh. This would to an extent address the economical imbalance but in its wake would lead to other administrative complications. The proposal might be appropriate in theory but in the current milieu appears impractical.

The economic dominance of the Karachi metropolis in the province of Sindh has created its own dynamics which make separating Karachi from Sindh highly problematical and unless this dichotomy is successfully resolved separating the city administratively from the rest of the Sindh province by declaring it as an independent provincial entity would be unwise and dangerous.

MQM’s bid to make Karachi a separate province basically stems from their inability to convince PPP to implement the LG system in the province as the party had pledged in their election manifesto. On the other hand, PPP’s reluctance to establish an LG system where much of the provincial revenue generated by the city would come under control of LG elected officials of the metropolis has a genuine basis. Since MQM continues to dominate the city’s political landscape, it is likely to sweep any LG election in the current ambiance and in the process the party would control a major chunk of the city’s revenue that falls under the provincial jurisdiction. This would leave PPP, the party in power with very little to address the needs of the rest of the province. Both MQM and PPP will have to negotiate and resolve this thorny issue in a manner where from the available provincial economic pie of the city, LG elected officials are given the fair share of its financial resources without compromising the needs of the rest of the province.

It should be remembered that the Urdu speaking public who are the core supporters of MQM since 1988 still remain the largest ethnic group in the city but the changes in its demography from the beginning of the current century has reduced their advantage to an extent. Hopefully with the implementation of computerized voting system for future elections at all levels, the charges of electioneering fraud would be significantly curtailed and the result would be a true reflection of the will of the citizens of Karachi – MQM could still dominate, or its overall superiority might be marginally or even significantly dented. Under such a level playing field other parties should not fear about their mandate being stolen through unfair means. No party, therefore, should oppose or hinder the holding Local Bodies elections and installing a functioning and legitimate LG in the city, once the revenue sharing aspects of the system is amicably resolved.

In conclusion, it is apparent that PPP’s refusal to implement the LG system in the province has prevented MQM from exercising any meaningful control over the city’s administration despite receiving a heavy mandate from its citizens in elections at all levels. This in turn has made them raise the issue of Karachi being declared a province in its own right. If PPP and MQM can agree to a formula where in an LG system the city’s revenue is shared in an equitable manner that ensures a balance between the needs of the city and that of the province, LG system would become a reality and with it the demand of MQM to declare Karachi an independent provincial entity would very likely subside at least for the present.

End Notes

1 Details gleaned from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presidencies_and_provinces_of_British_India accessed on 25 September 2014

2 See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sindh accessed on 25 September 2014

3 Ibid

4 See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Capital_Territory_%28Pakistan%29 accessed on 26 September 2014

5 See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Pakistan accessed on 26 September 2014

6 Budhani, Azmat; Gazdar, Haris; Kaker, Sobia; Mallah, Hussain B (2010) The Open City: Social Networks and Violence in Karachi, Collective for Social Science Research Working Paper no. 70.