Democracy, as an ancient and evolving system of governance to this day, has achieved general acceptance and recognition as a universal value. However, when it comes to the democratization process, every nation must play its own instrument in the symphony of its unique culture. All nations are consciously to undergo the evolutionary stages of human development and values as individuals, civil societies and organizations must undergo.

However, the most difficult and important question of our times not only for the Muslim world but also for the West and the rest remains: Is it conceivable for the project of liberal democracy to be reconciled with Islam and/or other major religions around the world?

Most certainly the deeper and closer examination by many Muslim scholars of past and present have clearly answered this most difficult question in the affirmative. To begin with, true Islam has always been moderately secular, open, liberal, tolerant and inherently democratic. It is indeed very sad that the Muslim world lost out over the last several centuries on these very basic Islamic democratic virtues and values that are proven to be universal today.

As a matter of fact, democracies around the world have been lately failing to deliver what they were supposed to deliver and even Western Democracies are in deep trouble today. Recent events in the Middle East and their repercussions in other parts of the world have refocused global public attention on the current unfolding story of democracy. It is in this context that we must presently re-examine the question of democracy as a universal value.

Even for the West in the 21st century, it is certainly very clear at this point that the rise of democratic ideas having come out of secularism turns out to be deeply flawed and misleading. In recent decades a significant number of Western scholars have started challenging the secular view, arguing that the basic tenets of modern political theory (not unlike Islamic and Judaic political thought) came explicitly out of religious ideas. What’s more, they have been lately focusing on the century that had preceded the European Enlightenment — a period also called “the Biblical Century” — in which many seminal thinkers from Hobbes to Harrington to Locke had turned to the Bible for their insights. Democracy in Europe was thus born out of religious principles and universal values importantly still allowing the separation of church and state.

Interestingly and indeed historically democracy had continued to evolve in the East and the West over the centuries subsequent to Judeo-Christian and Greco-Roman eras, thus fusing with the Islamic city state of Medina in the 7th century A.D. Islam reinstituted the legacy of prophet Moses (Pbuh) about 2000 years later and produced a dynamic system of Islamic democratic principles, universal values, market economics and communal politics during the time of prophet Muhammad (Pbuh).

The prophet of Islam (Pbuh) founded a civil society beginning in the city-state of Medina (C. 622-632) – an Ummah of democracy (of equal citizenship for Muslims and non-Muslims through a mutually agreed upon and signed constitution) that embodied and applied the Quranic and universal democratic values. The prophet (pbuh) himself taught the early Muslims the culture of democracy in Islam emphasizing a system of freedom, justice, equality and human rights.

The concepts of liberal and democratic participation inherently continued in the early Islamic Rashidun period (C. 632–661) spanning a vast geography from the Arabian Peninsula and the Levant, to the Caucasus in the north, North Africa from Egypt to present day Tunisia in the west, and the Iranian plateau to Central Asia in the east. It was the largest caliphate in history up until that point. Democracy continued during the early centuries of Islamic civilization including its early golden age when the development of democracy eventually came to a halt following the Sunni–Shia split between the Abbasid and the Umayyad.

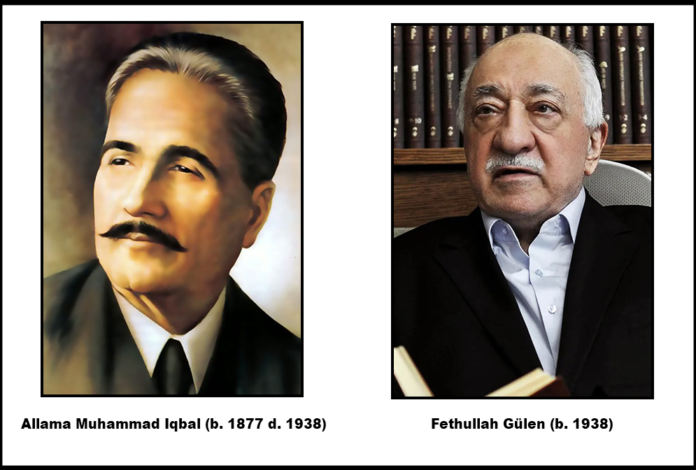

Two of the renowned Muslim thinkers and philosophers, Allama Muhammad Iqbal (b. 1877 d. 1938) and Fethullah Gülen (b.1938) and their ideas about democracy in the Islamic context are very similar. Over fourteen hundred years later since the inception of Islam, the modern Islamic philosopher, Muhammad Iqbal, viewed the Islamic prophetic state of Medina being an ideal democratic State and the Caliphate of Rashidun as being also compatible with genuine democracy.

He had also welcomed the formation of “popularly elected legislative assemblies” in the Muslim world in recent times as a “return to the original purity of Islam.” He argued that Islam has had the “gems of an economic and democratic organization of society”, but that this growth was stunted by the monarchist rule of Umayyad Caliphate, which established the Caliphate as a great Islamic empire but led to political Islamic ideals gradually being “re-paganized” and the early Muslims began losing sight of the “most important potentialities of their faith.”

Allama Iqbal had indeed made a proposal of spiritual democracy to the ummah in his “Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam” in his 6th lecture in 1930.We find that many Islamic scholars of today have accepted the idea of democracy and Islam being inherently compatible. Iqbal indeed did not like the idea of importing the Western democratic system and transplanting it as such in the Islamic world because of its radical secular stance.

He still suggested in his writings that there was no alternative to democracy in the Muslim World. Iqbal observed that if the foundations of democracy were to rest upon spiritual and moral values, it would be the best political system for the world. He wrote in the “The New Era” July 28th, 1917 issue: “Democracy was born in Europe from economic renaissance that took place in most of its societies. But democracy in the Islamic context is not to be developed from the idea of economic advancement alone; it is also a spiritual principle that comes from the fact that every individual is a source of power whose potentialities are to be developed through virtue and character.”

Allama Iqbal further stated that a universal democratic system is to be established on the principles of freedom, equality, tolerance and justice. Therefore the principles of democratic rules are to be reconciled to the fundamental aspects of Islam.

Fethullah Gülen argues that democracy in spite of its shortcomings is now the only viable political system, and people should strive to modernize and consolidate democratic institutions in order to build a society where individual rights and freedoms are respected and protected, where equal opportunity for all is more than a dream. According to Gülen, mankind has not yet designed a better governing system than democracy.1

Like Iqbal, Gülen also maintains that as a political and governing system, democracy is, at present, the only alternative left in the world. However, in his understanding democracy, in its current shape, is not an ideal that has been reached but a method and an ongoing process “that is being continually developed and revised”.2

He argues that “it’s a process of no return that must evolve, develop and mature. Democracy one day will attain a very high level. But we have to wait for the interpretation of time”.3 Gülen powerfully states that:

Democracy has developed over time. Just as it has gone through many different stages, it will continue to go through further evolutionary stages in the future to improve itself. Along the way, it will be shaped into a more humane and just system, one based on righteousness and reality. If human beings are considered as a whole, without disregarding the spiritual dimension of their existence and their spiritual needs, and without forgetting that human life is not limited to this mortal life and that all people have a great craving for eternity, democracy could reach its peak of perfection and bring even greater happiness to humanity. Islamic principles of equality, tolerance, and justice can help it do just that.4

Gülen does not see a contradiction between “Islamic administration” and “democracy”:

As Islam holds individuals and societies responsible for their own fate, people must be responsible and accountable for governing themselves. The Qur’an addresses society with such phrases as: “O people!” and “O believers!” The duties entrusted to modern democratic system are those that Islam refers to society and classifies, in order of importance, as “absolutely necessary, relatively necessary, and commendable to carry out.” People cooperate with one another in sharing these duties and establishing the essential foundations necessary to perform them. The government is composed of all of these foundations. Thus, Islam recommends a government based on a social contract. People elect the administrators, and establish a council to debate issues. Also, the society as a whole participates in auditing the administration.5

Islam, for Gülen, is not a political project to be implemented from top-down. It is a repository of discourse and practices for the evolution of a just and ethical civic society. He strongly states that:

Islam does not propose a certain unchangeable form of government. Instead, Islam establishes fundamental principles that orient a government’s general character, leaving it to the people to choose the type and form of government according to time and circumstances.6

Because he is critical of the abuse of Islam in politics, he constantly criticizes discourses, rhetoric, practices and policies of the “political Islam”.

Thus in Turkey, his native country, Gülen, while encouraging everybody to participate in elections and to vote, never spells out any one particular party or a candidate. He gives the guidelines, such as honesty, being truly democratic, being suitable for the job, the most suitable socio-political conditions so on and so forth. In any party, one could find such suitable candidates. At the end of the day, if every voter behaves in this manner, all the elected ones will be in tune with Gülen’s Islamic ideal, regardless of the party affiliations. Most importantly, as he does not categorically affiliate with any of the political parties in particular, they will always be hopeful and will try to earn his genuine sympathy. Moreover, his supra-party discourse will easily attract everybody from all walks of life.

Regarding an Islamic state, it is obvious that he is in favor of a bottom-up approach and his desire is to transform every individual (as did ‘Allama Iqbal) as an ideal & close to perfect (insane-e-kamil) human being that cannot be accomplished by coercion or from the top-down approach.7 Even if democracy could never be perfect, it will continue to evolve towards the prophetic ideal of justice and perfection.

The early Islamic philosopher, Al-Farabi (c. 872-950), in one of his most notable works Al-Madina al-Fadila, conceptualized an ideal Islamic state founded by the prophet which he compared to the Plato’s Republic (a Socratic dialogue, written by Plato around 380 BC, concerning the definition of justice , the order and character of the just city-state and the just man). Al-Farabi departed from the Platonic view in that he regarded the ideal state to be ruled by the prophet himself instead of the philosopher king envisaged by Plato. Al-Farabi argued that the most ideal state was the city-state of Medina when it was governed by Prophet Muhammad, as the head of the state, and as a prophet in direct communion with God whose laws were revealed to him. In the absence of the prophet, Al-Farabi considered democracy as still close to the ideal state, regarding the order of the Rashidun Caliphate as exemplified within early Muslim history. However, he also maintained that it was from democracy that imperfect state started to emerge, noting how the order of the early Islamic Caliphate of the Rashidun caliphs was later gradually replaced by a form of government resembling a monarchy/authoritarianism under the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties.

Prophetic path (exemplified by Muhammad Pbuh) brought ideal democracy to practice. Rashidun caliphs’ democracy even if fulfilled the democratic norms did not reach the ideal or come closer to the prophetic model. The rest of us around the world will never be prophets to ever reach that ideal but we have, at least a prophetic path & an example of Rashidun to follow to make democracy as best as we common human beings can without mixing religion and state in the age and times of today.

As noted here, Gulen advocates an Anatolian-Islam based on prophetic path or Quran and Sunnah based Sufi thought that puts an emphasis on tolerance and insightful Turkish type modernity as an alternative to Saudi or Iranian versions or images, emphasizing that this discourse of Islam is not in contradiction to the modern world. His discourse represents a kind of “moderate Islam”; even though he strongly rejects such a definition as in his view Islam (based on the Qur’an and Sunnah) to begin with is already moderate and a middle way.

True Islam and its middle way engages others and searches for common grounds through shared universal values such as justice, freedom, peace, rule of law, human rights, and democracy as a universal value. However, on the issue of civic Islam and democracy, one should remember that the former is a divine and heavenly religion for the public sphere, while the latter is a form of government developed by humans for governance by the state.

Democracy itself is not a unified system of government; it should not be presented without an affiliation. In many cases, another term, such as social, Islamic, liberal, Christian, or radical is added as a prefix to democracy. One form of democracy labeled as such may not be considered by the others as democracy.

Generally speaking democracy is frequently mentioned in its unaffiliated form, ignoring the plural nature of democracies. In the Muslim World, there are those who speak of Islam as tantamount to politics, which is, in fact, only one of the many perceptions of Islam. Such perceptions have resulted in varied positions on the subject of reconciliation of Islam and democracy. Islam and democracy are not to be seen as being opposites; it is evident that they may differ in some important ways.

According to one of these conceptualizations, Islam is both a religion and a political system. It has expressed itself in all fields of life, including the individual, family, social, economical and political spheres. From this angle, to confine Islam to only faith and prayer is to narrow the field of its interactions and its interpenetrations. Many ideas have been developed from this perspective; and more recently these have often caused Islam to be perceived as an ideology. According to some critics, such an approach made Islam merely one of many other political ideologies.

The vision of Islam as an ideology is totally against the spirit and essence of Islam that promotes the rule of law and openly rejects oppression against any segment of the society. This spirit also promotes actions for the betterment of society in accordance with the view of the majority.

Majority of those who follow a balanced and moderate view of Islam believe that it is much better to consider Islam as inherently compatible and complementary to democracy rather than thinking of Islam as a political ideology. Such an Islam will play a much better role in the Muslim world through enriching local forms of democracy and extending it in a way that helps humans develop a better understanding of the relationship between the spiritual and material worlds. Iqbal and Gülen both believed that Islam would enrich democracy in answering the deeper needs of humans, such as spiritual satisfaction, which cannot be fulfilled except through the remembrance of the Creator.

Islam’s Tawhidic Worldview includes Deen-o-Duniya (sacred and secular).This Worldview (Unity of God) has two major components that link the spirit and ethos of Tawhid which harmonize other worldly (the Hereafter) with human spiritual awareness (Al-Deen) and the worldly/secular (Al- Duniya) realm. This mutually reinforcing process of righteous and universal values is referred to as promotion of goodness (amr bil ma’ruf) and prevention of evil (nahi anil munkar) in all aspects of human life including democratic governance.

From the time of the prophet (Pbuh), Islam has had a perfect template for democratic governance. Islam has always had integrated moderate (or soft) secularization, unlike the French tradition that bans religion in public space. Radical secularism is indeed anti-Western and anti -Islamic. Islam, on the other hand certainly and importantly includes religion into the public domain as an instrument of social transformation and strength. It is indeed also able to create a Muslim spiritual identity compatible with democracy and pluralism. There can be no obstacles to democracy in Islam when all its pillars are democratic, and even democracy needs a strong spiritual dimension as one of the values Islam and democracy both represent is spirituality. A Strong civil society and democratic relations are like the chicken and the egg. We do not know which one must come first, but we know that their existence depends on each other.

There are those who pronounce, in the name of religion, that Islam and democracy cannot be reconciled. This perception of mutual incompatibility extends to some pro-democracy groups as well. The argument that is presented is based on the idea that the religion of Islam is based on the rule of God (or His sovereignty), while democracy is based on the view of humans (human sovereignty), which opposes rule of God. Again in Iqbal’s and Gülen’s understanding, however, there is another idea that has become a victim of such a superficial comparison between Islam and democracy. The phrase, “sovereignty belongs to the nation unconditionally,” does not mean that sovereignty has been taken away from God and given to humans. On the contrary, it means that sovereignty is entrusted to the humans by God, that is to say, it has been taken from the oppressors and dictators and given to the community members. To a greatest extent the ideals and democratic practice of prophets Moses and Muhammad, and to certain extent, the era of the rightly-guided Caliphs of Islam illustrate the practical application of the norms of democratic virtues and values very well. Cosmologically speaking, there is no doubt that God Almighty is the sovereign of everything in the universe. Our thoughts and plans are always under the controlling power of such an Omnipotent. However, this does not mean that we have no will, inclination or choice.

Humans are free to make choices in their personal lives. They are also free to make choices with regard to their social and political actions. Some may hold different types of elections to choose lawmakers and executives. There is not only one way to hold an election, as we can see this was true even during the time of both Prophets Moses and Muhammad (Pbuh), and during the time of the rightly guided four Caliphs. The election of the first Caliph, Abu Bakr (ra), was different from that of the second Caliph ‘Umar (rta) and Uthman’s (rta) election was different from that of ‘Ali (rta), the fourth Caliph. Only God knows the most accurate and the best method of election.

Democracy is certainly not an immutable form of governing. Looking at the history of its development, one can see mistakes made that are followed by corrections and improvements through an uninterrupted democratic process. Some have even spoken of thirty types of democracy. Due to ongoing changes and evolution of democracy, some have looked at this system with reluctance. The Muslim world, in recent times, has not always viewed democracy with great enthusiasm. The lack of enthusiasm, the despotic rulers in the Islamic world who see democracy as a threat to their despotism (supported by external and vested interests), presented yet another obstacle to democracy in Muslim nations.

Islam actually and inherently links democracy to the core Islamic values of justice, human rights and freedom. Justice in the Islamic context is an absolute and not a relative value like freedom, equality, accountability, fairness, openness, transparency and trust. All of these relative values enhance justice and are also individually and collectively to be exercised/ practiced for the ongoing evolution of democracy and its further maturation. Thus justice must be adhered to in all cases and under all circumstances, against enemies as well as with friends – with friends, magnanimity; with enemies, tolerance. Even if the banner of Islam is held high and its teachings adhered to but justice has not been served, the message would be emptied of content; and the means would fail to achieve the ends.

We should use a principle that exists in all cultures of the world, “Do unto others as you would like do to you.” This expression definitely points to one of the most important aspects of justice that heads both the list of ethical and the political concepts intimately intertwined. Justice has to be observed in the distribution of power as being talked about in the distribution of economic resources. Power no longer can remain the monopoly of the elite.

Democracy is the political face among the economic and judicial faces of justice. Of course, moderation within one’s being is the inner and very important spiritual face of justice. We need esoteric Justice/ freedom and exoteric justice/freedom at this point in time. This point was made by Jalal al-Din Rumi in the 13th century: “O kings, we’ve killed the enemy without/but a more evil enemy resides within.” Even if Rumi was not exactly talking about political freedom/justice in the modern sense, he was indeed talking about inner/spiritual freedom/justice with meaning and applications to spiritual aspect of democracy today.

Rumi further said: “Since the Prophet guided us freely/ prophet bequeaths us freedom.” In truth, all prophets came to give us freedom. Rumi is someone who believed that inner justice and equilibrium were the highest order of perfection for human beings. Yet, when he wants to speak about the various aspects of prophet-hood, he deems freedom and liberty to be its most important aspect. Hence, whether it is within the self or in the external world, in society, freedom is the strong component of justice and we must always strive for it. And freedom is not an abstract concept; it has clear consequences in society, and if you prevent freedom, you can easily be criticized and challenged to explain why you didn’t give freedom its due.

Justice as seen over the past several centuries, in political conduct of rulers, has not always sufficed for the ruler to be just without democracy.

In this realm of “democracy” it is said: “Let there be a separation of powers. Let there be a strong judiciary. Let the people’s votes play a part in choosing the rulers.” In order for the people to be able to choose, they must be free.

Three democratic steps summarized here are: freedom to installing, criticizing and dismissing rulers. When the people can take these three steps, we can say that we have achieved political justice. These steps can’t be taken without freedom, so justice hinges on freedom that is subdivision of justice as also emphasized by Abdul karim Soroush8. Freedom is a human right.

We must aim for democracy of just outcomes and not simply procedures. We must balance our appreciation for the nuts and bolts of democracies with a discriminating sense of their limitations, particularly in terms of the unjust outcomes that even the most advanced democracies still tolerate. We must pay attention to the destruction of values and culture by unbridled consumerism and the unacceptable disparities in material circumstances and life chances that characterize all of the democracies, even the Western democracies including the United States.

For the past several centuries, the Muslim world has been experiencing a severe crisis. The current political, ideological, and religious polarizations in the world have unfortunately been posing an increasingly serious threat to the international peace and security.

Today we have before us the greatest challenges and divisions—to help break down the walls between the East and the West, between the North and the South, between Muslims and Christians, between all religions, all civilizations and all cultures, and to bridge the great divide and recognize our common humanity and common values. Certainly, the interaction of Islam and the modern world does not mean clash of civilizations or the end of history. The Islamic world committed to the vision of contemporary universal civilization and crowned with the ideal interpretations of Islam, democracy and secularism is bound to bring about reconciliation and integration.

Enlightened Muslim intellectuals in the likes of Iqbal and Gülen have offered some very valuable suggestions and excellent solutions to those seeking the right path.

References

1For details, please see, Yilmaz, Ihsan, Muslim laws, politics and society in modern nation-states (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005), chapter 8.

2Gülen, Fethullah, a Comparative Approach to Islam and Democracy, SAIS Review, Volume XXI, No. 2 Summer-Fall 2001, pp. 133-138, 134.

3Unal and Williams, op. cit., 150.

4Ibid., 137.

5Gülen, a Comparative Approach to Islam and Democracy, op. cit., 135-136.

6Ibid. 134.

7Altınoğlu, Ebru, Fethullah Gülen’s Perception of State and Society (Istanbul: Bosphorus University, 1999), 102.

8‘Ali Asghar Seyedabadi; An interview with Abdul karim Soroush: Democracy, Justice, Fundamentalism and Religious Intellectualism, December, 12, 2005. http://www.drsoroush.com/