Treason case has been registered against Pakistan High Commissioner Abdul Basit and freedom movement leader Shabir Ahmed Shah in an Indian court. A petition has been filed in district court that Basit had met Shabir Shah in contravention to the Indian government orders. The petitioner termed the move as ‘treason’ and a conspiracy against India. Bizarrely court accepted the petition and ordered to register the case. Kashmir issue should be looked at dispassionately; the aim of High Commissioner’s meetings with the Kashmiri leaders was to find a viable solution to the issue. Pakistan has been holding talks with Kashmiri leaders, on all such occasions, for the last 20 years. Previous Indian prime ministers from both side of the aisle, including BJP stalwart Atal Bihari Vajpayee, had happily lived with the practice. Indian diplomats in Islamabad also meet people from all hues.

Going by the Indian tradition of stalling and subverting numerous peace processes with Pakistan on flimsy pretexts, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has also failed his personal leadership test by cancelling a foreign secretary level meeting with Pakistan. The peace process stands scuttled, at least for the time being, however no one is really surprised. India was working on it since Modi’s assumption of power.

Proximate cause to cancel the talks is India’s anger over the preparatory meetings that Pakistan’s High Commissioner to India held with the political leadership of Indian Held Jammu and Kashmir (IHJ&K).

Through this error of judgment, India has bluntly conveyed to Pakistan to choose between an Indo-Pak dialogue or interactions with the Kashmiri leaders. Drummed up hype about revocation of article 370 of the Indian constitution and asking UN Military Observers Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) to vacate the building were good indicators towards this happening. A more plausible reason for this kneejerk reaction is India’s mounting irritation with the likely fizzle during the forthcoming elections in Kashmir expected in October and November. Such earlier elections have been marred with low turnout, dubious funding and other manipulations.

Modi himself made some hard-hitting statements against Pakistan during his visit to Kashmir. He was greeted in Kashmir by a complete shutter down and wheel jam strike. To ward-off the embarrassment, he gave carefully constructed incendiary statements in the highly sensitive region of Kashmir, while addressing Indian troops. In his toughest statement on Pakistan to date, Modi said that Pakistan “has lost the strength to fight a conventional war but continues to engage in the proxy war of terrorism.” He chose a politically charged venue for his outburst—Kargil.

Calling off a fledgling peace process on the basis of imagined provocations has exposed the dubious intent behind the public invitation to talks. Having ridden a wave of Hindu nationalism and anti-Pakistan rhetoric to office, Modi is more inclined to play to domestic gallery than promoting dialogue with Pakistan. Curiously, there have even been claims in some Indian quarters that the meeting between Pakistan’s High Commissioner and IHJ& K leadership in India would be akin to Indian diplomats engaging Baloch separatists in Pakistan. Needless to state the obvious that while Kashmir has been an internationally accepted disputed area from the very inception of Pakistan and India, Balochistan became part of Pakistan through wilful expression of intent by the legitimate representatives of the Baloch people.

Kashmir is a disputed territory over which two countries have fought three wars. In a major aggressive military manoeuvre “Operation Meghdoot” in Kashmir, India moved its troops and occupied Siachen glacier in 1984; India gained more than 1,000 square miles of territory because of this military operation. Siachen glacier is the highest battleground on the earth where India and Pakistan have fought intermittently since 1984. Kashmir dispute is on the UN agenda since 1948, when India took the issue to the UN. There are over a dozen UN resolutions on the subject; and UNMOGIP is permanently stationed in the two countries to monitor the UN mandated and Simla Agreement endorsed Ceasefire Line/Line of Control in Kashmir. There have been 57 border violations by the Indian troops since July last year for which Pakistan has served demarche’; all violations have been reported to UNMOGIP.

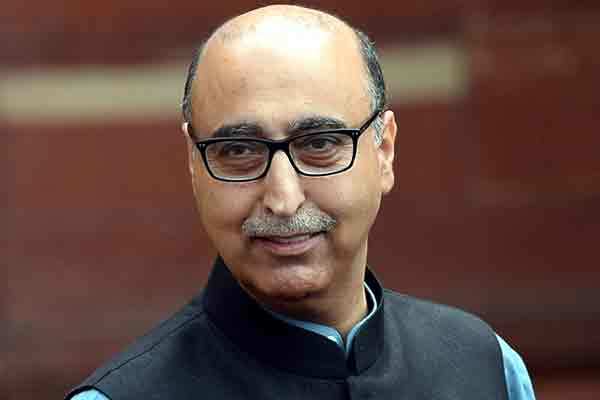

After India called off the talks, Pakistan’s High Commissioner to India Abdul Basit responded that calling off the August 25 talks was a “setback” but hoped that it would not discourage the two neighbours from resolving the Kashmir issue. Addressing a press conference at Foreign Correspondents’ club in New Delhi, Basit defended his meetings with pro-plebiscite Kashmiri leaders and said that he did not breach any protocol by holding talks with them. “This has been a long-standing practice…It is important to engage with all the stakeholders to find a peaceful solution to the issue…”. Modi had raised expectations that he would work harder at resolving Pakistan-India differences when he took the step of inviting Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to his inauguration in May 2014. Nawaz Sharif obliged him despite an earlier refusal by Dr Manmohan Singh to attend Nawaz Sharif’s inaugural. The photo of the two men shaking hands came to symbolize the promise of that moment; now that pictorial may fade into oblivion.

Internationally, Modi has been faulted for cancelling the meeting. “There are no two countries in the world that need to talk, and talk regularly, more than these nuclear-armed South Asian neighbours whose tensions must be carefully managed”, the New York Times has recently reported in a lead article. Noting the significance of talks, the NYT said that “cancelling the meeting was an over-reaction on India’s part, especially when it could have served as an opportunity to discuss grievances and press for a solution…There will always be political excuses not to take risks”, the newspaper opined.

It is all too easy to gauge how Narendra Modi could use a hard-line stance on Pakistan to reap domestic dividends. While the domestic and international dimensions of a typical national policy are intricately interconnected, India’s Pakistan policy should not become hostage to Indian domestic concerns alone. Without simultaneous commitment at the very highest levels of political power, Pakistan-India relations will never truly be able to move forward. As of now Nawaz Sharif faces criticism about the utility of his misplaced fondness for India.

Modi, who won a huge victory in the May election, is in the strongest political position, while Nawaz Sharif would also emerge equally stronger after the ongoing political soap-opera in Islamabad sit-ins fizzles out in a week or so. Hopefully, Narendra Modi will outgrow his anti-Muslim and anti-Pakistan shadow of yester years. Choice is with him, whether he wants to leave behind a legacy of a prudent statesman or go down in the history as a mere RSS zealot. Suspension of dialogue would not cause any material setback to Pakistan, it can wait and timeout Modi. However, rationality and continuity should underwrite the bilateral relationship. What’s needed is a meeting between the two leaders to establish a continuing dialogue. Next month’s UNGA meeting in New York offers a good venue. Announcement of fresh schedule of secretary level talks could help create forward movement during the prospective summit on the sidelines of the UNGA session.

Since coming into power Modi continues to proceed with hostile attitude towards Pakistan. He took the decision to cancel foreign secretary talks without taking External Affairs Ministry into confidence. Emerging developments should be an eye opener for Islamabad and appropriate steps should be taken to fully guard the national interests.