Introduction

The sea has always remained an arena for contest of power between the nations. Since it provides economical means of transportation, 90% of the world trade is through sea.2 Historically naval warfare has been used to gain control of the sea for its use to own advantage and deny enemy the effective use of sea. Generally, this advantage has been achieved by battle (destroying enemy fleet) or blockade (restricting fleet within their ports and cutting off sea lines of communication). Over the last hundred years, naval technology has progressed from steam ships carrying guns and torpedoes to nuclear powered aircraft carriers, ships and submarines equipped with state of the art aircraft, helicopters, ballistic missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles with network centric warfare capabilities. Despite transformation in naval technology, it is considered that operational concepts underpinning the employment of maritime power have changed very little since 19th century theorists, Mahan and Corbett. The events of the second half of the 20th century and early 21st century highlights that even in the era of Mahan and Corbett different schools of thought prevailed, suggesting over the last hundred years the concepts of employment of naval power have changed considerably. This change is primarily evident in peacetime employment of naval forces and to a lesser extent in war time employment as well. Major reasons for this change are the birth of international regulatory bodies, globalization, rise of non-state actors and popularity of strategies of cooperation over confrontation. All these changes enable comprehensive maritime security to maintain good order at sea.

Blue Water and Continental School of Thought

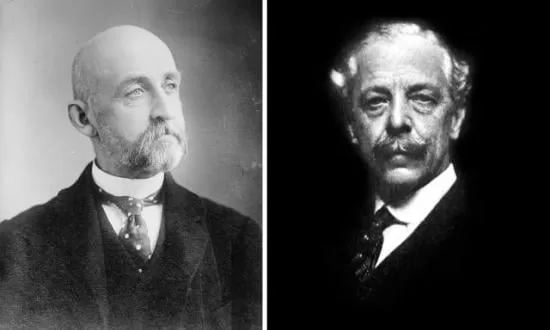

Before analysing the change in employment of maritime power, it is necessary to see what were the different concepts prevailing in the era of Mahan and Corbett. In the late 19th and until the mid-20th century the most influential naval theorists were primarily concerned with the study of sea power as a whole and naval strategy in particular. These naval thinkers can be divided into two schools of thought; Blue Water and Continental School. It is considered that the American Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840–1914) and the British naval historian and theorist Sir Julian Corbett (1854–1922) were the leading naval thinkers of the Blue-Water school who focused on the need of a large fleet composed of capital ships. They also tried to impress on politicians and the public that the navy operates independently. They emphasised on offensive naval strategy and decisive battle as the chief method of achieving command of the sea. On the other hand, main representatives of the continental school of naval strategy were French Vice Admiral Raoul Castex (1878–1968) and German Vice Admiral Wolfgang Wegener (1875–1956). They recognized the interdependence and need for close cooperation between the navy and army. They had slightly different views of command of the sea and the ways of achieving it. They considered naval strategy as an integral part of national strategy. They also recognized that the success in a war ultimately depends on the outcome of the struggle between the opposing armies.3 The thinkers of both schools presented their theories in the early half of the 20th century, but the events of two world wars and conflicts thereafter proved that the continental school of thought is relevant in the contemporary era.

Changes in Employment of Maritime Power

In World War II, the Battle of the Atlantic highlighted the importance of submarine warfare and convoy escorting, while the Normandy landings and battles of the Pacific theatre underscored the importance of naval air power, amphibious warfare and joint operations. None of these battles proved the validity of the concept of decisive battle, the primacy of capital ships or the Blue Water School of thought. Recent examples of these facts are Operation Desert Strom, Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom where maritime power was used as an enabler of air strikes and amphibious warfare because technology has enabled naval forces to influence events on land and in the air. Extended range guided munitions, naval air power and anti-air warfare capabilities can directly affect operations on land and in the air whereas advance helicopters can deliver forces from sea deep into the hinterland in battle ready conditions.4 Hence, it can be argued that operational concepts for employment of maritime power have transformed from independent naval operations, decisive battles and blockades to joint warfare, expeditionary operations and influencing events on land.

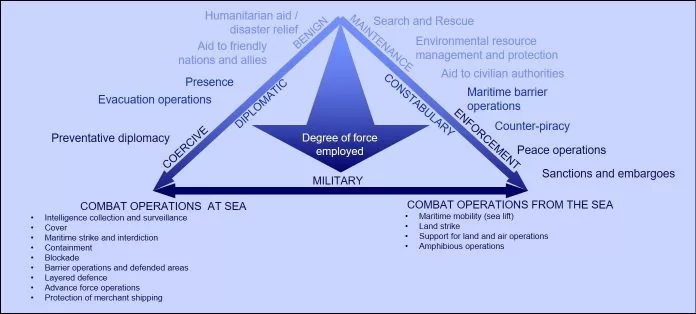

In order to witness the change in the employment of maritime power, it is important to see different roles/tasks that can be assigned to naval forces. These roles are based on the strategic concepts of the employment of maritime power,5 attributes6 and limitations of maritime power.7 The Australian Maritime Doctrine provides a good detail of various tasks for employment of maritime power;8 these include military, diplomatic and benign tasks. A diagram depicting various details of these tasks is depicted below.

Factors Leading to Shift in Roles of Maritime Power

A closer look at the events of last few decades makes it clear that focus of employment of maritime power has shifted from military tasks to diplomatic and constabulary roles. There can be different reasons for this gradual shift from coercive to benign tasks. First is the effect of the prolonged Cold War. During both world wars, belligerents used their sophisticated armadas to maintain Sea Control or Denial of the Sea to the enemy in order to protect their interests. Contrarily, during the Cold War, despite availability of technologically advanced fleets on both sides, no decisive battle or other such incident took place. Nuclear Deterrence and the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction precluded both sides from any misadventure. Second reason is the birth of international institutions, particularly the United Nations to regulate world affairs. Development of the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS 1982) is another breakthrough in this regard which accepts sea as ‘Common heritage of mankind’,9 thus providing a common medium for cooperation between the nations. Although few nations have not signed/ratified UNCLOS,10 even then there is general conformity to the principles and provisions of UNCLOS. The International Court of Justice (ICJ), International Maritime Organization and International Tribunal on Law of the Sea (ITLOS) have provided platforms for peaceful resolution of conflicts. To date 21 maritime disputes between nations have been submitted to ITLOS11 and 152 cases have been submitted to ICJ.12 Hence it can be argued that struggle to control the sea in era of Mahan and Corbett was actually based on the realist school of thought for ‘survival of the fittest’ in an anarchic world whereas now international regulatory bodies provide platforms for peaceful resolution of conflicts.

The third factor is the effect of globalization. In the contemporary world, the development in monetary systems, technology and telecommunication has shrunk the world into a global village where goods, services and finances can be easily transferred from one part of the world to another with considerable ease. In this era, effects of blockade can be easily achieved by international monetary restrictions and trade embargoes rather than decisive battles at sea or actual seizing of cargoes. The trend has shifted from unilateral blockades to United Nations authorized sanctions to achieve similar effects. The sanctions on Iraq after the Gulf War are an example in this regard. Hence, it can be argued that the cumulative effects of the prolonged Cold War, UNCLOS, international regulatory bodies and globalization have changed the trends of employment of maritime power where effects of blockade and decisive battle can be achieved through alternate means.

Another factor is the growing popularity of cooperative maritime security arrangements and focus on the littoral environment. This phenomenon has roots in philosophy of cooperation over confrontation and rise of non-state actors. The philosophy of cooperation seeks win-win situations between different contenders in any field. Hence, leading navies in the world are operating in harmony to each other to safeguard their mutual interests; to maintain good order at sea. The major threat to good order at sea is the rise of non-state actors and asymmetric warfare. Now a handful of non-state actors can rely on Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) technologies to wage asymmetric warfare against leading navies of the world. The attack on USS COLE (DDG-67) on 12 October 2000 and the attack on the French tanker LIMBURG on 6 October 2002 is testimony to the fact. Moreover, the same technologies can be utilised by quantitatively and qualitatively inferior naval forces to threaten the interests of major powers. Threats by Iran to block the Straits of Hormuz are also an example of the same phenomenon. So the focus of the major navies of the world has shifted from open oceans to littorals, which can be exploited by non-state actors and small naval forces.

Cooperative Maritime Security Initiatives

Cooperative maritime security arrangements around the globe are manifestation of the concept of cooperation against non-state actors. Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) operations in the Gulf of Oman, North Arabian Sea and Gulf of Aden against terrorism and piracy are important developments. The United States (US) and China, two major peer competitors in the world, are also cooperating on the same lines. In June 2006, US Admiral Mike Mullen promoted the idea of Global Maritime Partnership (GMP) to protect trade routes, counter terrorists and interdict Weapons of Mass Destruction for a comprehensive maritime security. This brought a shift to US strategy from Cold War focus of Sea Control to a new idea of maritime partnership. Initially it was known as ‘Thousand-ship Navy’ but later on changed to Global Maritime Partnerships (GMP). The concept was presented in ‘A Cooperative Maritime Strategy for 21st Century Sea Power (CS-21)’. The emphasis was on cooperative security approaches to maritime security with both allied and non-allied naval powers.13 On the similar lines, in April 2009, on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of Chinese PLA (N) concept of ‘Harmonious Seas’ was presented. Chinese President Hu Jintao conveyed Chinese interest in increased international maritime security cooperation to build ‘harmonious oceans and seas’.14 Other evidence of these approaches is counter piracy deployments in the Gulf of Aden where ships from allied nations are operating under US, NATO and EU task groups while Russia, China and India have deployed their ships independently. Despite operations in various task groups, these forces are collaborating for safety of shipping in the area. The Shared Awareness and De-confliction (SHADE) is an initiative which began in 2008 as a mechanism for coordinating and de-conflicting activities between the countries and coalitions involved in military counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and the western Indian Ocean.15

A latest development which highlights the shift in employment concepts of naval forces is release of US Naval Operations Concept 2010 (NOC 2010) in May 2010. NOC 2010 expresses the ways naval forces will be employed to achieve the strategy conveyed in CS-21. CS-21 was published in 2007 and described a set of core capabilities for the US. Maritime Security, Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (HA/DR) have been added to the traditional core capabilities of Forward Presence, Deterrence, Sea Control, and Power Projection.16 More importantly the document is signed by US Chief of Naval Operations, Commandant of Marine Corps and Commandant of Coast Guard which is a depiction of integrated approach to common goal. The opening quote by Commandant of US Marine Corps General James T. Conway provides an indication of changing scenario:17

…while we are capable of launching a clenched fist when we must [,] offering the hand of friendship is also an essential and prominent tool in our kit. That premise flows from the belief that preventing wars means we don’t have to win wars.

Hence it can be argued that philosophy of cooperation over confrontation has also influenced the maritime strategies of the leading navies of the world. These navies have identified piracy, terrorism, non- state actors and asymmetric warfare as their common enemy while maintenance of good order at sea has been identified as common goal. Despite political differences major navies are operating in same theatre and developing systems for coordination and de-confliction.

Conclusion

Mahan and Corbett had a difference of opinion with their contemporaries of the continental school of thought. Although their theories were presented in the early half of the 20th century, subsequent events of the 20th and 21st century highlight that the continental school of thought is relevant in this era. Operational concepts for employment of maritime power have transformed from independent naval operations, decisive battles and blockades to joint warfare, expeditionary operations and influencing events on land. Cold War, UNCLOS, international regulatory bodies and globalization have changed the trends of employment of maritime power. Based on the philosophy of cooperation over confrontation, leading navies of the world have identified piracy, terrorism, non- state actors and asymmetric warfare as their common enemy. Maintenance of good order at sea has been realized as common goal and various international platforms and systems have been designed for cooperative security to achieve comprehensive maritime security. Thus it can be said that over the last hundred years the concepts of peace time employment of naval power have changed considerably. The war time employment has changed to lesser extent except technology has enabled naval forces to influence events on land and in the air.

Bibliography

Royal Australian Navy. Australian Maritime Doctrine. Accessed March 10, 2013. http://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Amd2010.pdf.

China sets sail on unity for Harmonious’ Seas. Shanghai Daily. April 24, 2009. Accessed April 6, 2013. http://www.shanghaidaily.com/sp/article/2009/200904/20090424/article_398735.htm.

Gaye, Christoffersen. China and Maritime Cooperation: Piracy in the Gulf of Aden. Accessed April 4, 2013. http://www.ispsw.de

International Court of Justice. Accessed April 10, 2013.

http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/index.php?p1=3

International Tribunal for Law of the Sea. Accessed April 10, 2013. http://www.itlos.org/index.php?id=10&L=0.

Shared Awareness and De-confliction. Accessed April 10, 2013. http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/ajax_init_view/t/1105.

Status of UNCLOS Ratification. Accessed April 10, 2013.

http://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/status.htm.

Vego, Milan. Naval Classical Thinkers and Operational Art. Accessed April 10, 2013. http://www.usnwc.edu/getattachment/85c80b3a-5665-42cd-9b1e-72c40d6d3153/NWC-1005-NAVAL-CLASSICAL-THINKERS-AND-OPERATIONAL-.aspx.

United Nations. United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea. Accessed April 10, 2013. https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/part11-2.htm.

United States Navy. United States Naval Operations Concept 2010. Accessed March10, 2013. http://www.navy.mil/maritime/display.asp?page=noc.html.

End Notes

2United States Naval Operations Concept 2010, accessed March 10, 2013, http://www.navy.mil/maritime/display.asp?page=noc.html, 13.

3Vego, Milan, Naval Classical Thinkers and Operational Art (Newport: US Naval War College, 2009), accessed April 10, 2013, http://www.usnwc.edu/getattachment/85c80b3a-5665-42cd-9b1e-72c40d6d3153/NWC-1005-NAVAL-CLASSICAL-THINKERS-AND-OPERATIONAL-.aspx, 17.

4Australian Maritime Doctrine, accessed March10, 2013, http://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Amd2010.pdf, 78 – 80.

5The strategic concepts for employment of maritime power include Command of the Sea, Sea Control, Sea Denial and Power Projection. Australian Maritime Doctrine, 71-75.

6Attributes of maritime power include mobility, readiness, access, flexibility, adaptability, sustained reach, poise and persistence, and resilience. Australian Maritime Doctrine, 86-92.

7Maritime power has limitations of transience, indirectness and speed. Australian Maritime Doctrine, 86-92.

8Australian Maritime Doctrine, 100.

9‘United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea’, accessed April 10, 2013, https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/part11-2.htm, article 136.

10The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea opened for signature on 10 December 1982 and entered into force on 16 November 1994. Several states out of 159 original UNCLOS signatories have yet to ratify. The US is one of the major countries which have yet not ratified the convention. ‘Status of ratification,’ accessed April 10, 2013,http://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/status.htm.

11‘International Tribunal for Law of the Sea,’ accessed April 10, 2013, http://www.itlos.org/index.php?id=10&L=0

12‘International Court of Justice,’ accessed April 10, 2013, http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/index.php?p1=3

13Gaye. Christoffersen, China and Maritime Cooperation: Piracy in the Gulf of Aden (Berlin: ISPSW, 2010), 7, Accessed April 4, 2013, http://www.ispsw.de.

14China sets sail on unity for Harmonious’ Seas, Shanghai Daily, April 24, 2009, http://www.shanghaidaily.com/sp/article/2009/200904/20090424/article_398735.htm.

15‘Shared Awareness and De-confliction,’ accessed April 10, 2013, http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/ajax_init_view/t/1105.

16NOC 2010, 2.

17NOC 2010, 2.