The world to this day indeed owes a tremendous amount to the Muslim world for the many groundbreaking scientific and technological advances that were pioneered during the Golden Age of Muslim civilization (particularly between the 9th to the 13th centuries) and overall between the 7th and 16th centuries. The world had overlooked these achievements and contributions of close to a thousand years, presently being shared in a book,” 1001 Inventions and the Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization” published and released by National Geographic on 26/01/2012. The book is an official companion to the 1001 Inventions’ exhibitions that have been taking place around the globe and the USA, which were amazing for the audiences globally and at the California Science Center (CSC) in Los Angeles. An exhibition had also opened at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, DC, at the beginning of August 2012.

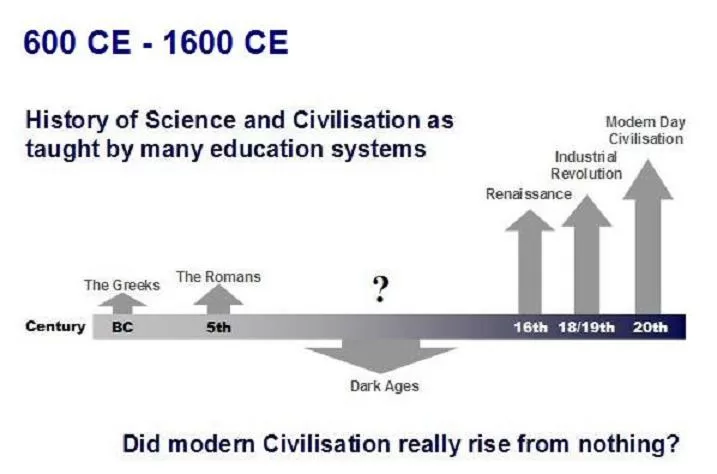

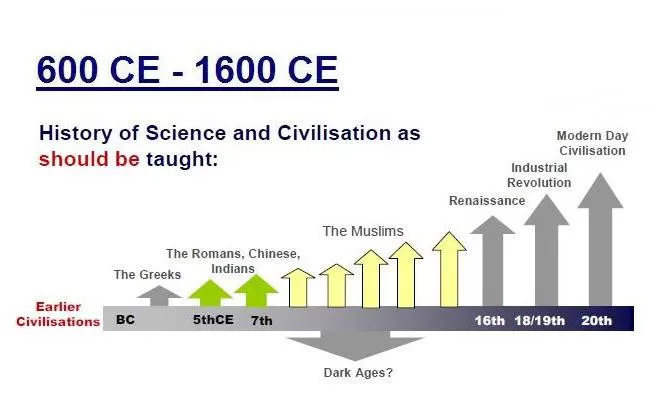

1001 Inventions highlight how many of the most important scientific and technological discoveries and building blocks of modern civilization came out of Muslim society during the centuries after the fall of ancient Rome — a period known as the Dark Ages in European civilization. However, while the Western World was in the doldrums, a renaissance had been occurring in the Muslim world. The book highlights these outstanding achievements of the multiple sciences and learning’s behind them.

The Western culture, from early down through the end of the middle Ages [the Early Middle Ages 600-1000, the High Middle Ages 1000–1300, and the Late Middle Ages 1300–1492 was under the dominant influence of Al-Andalusia (the Islamic Spain) and the broader Islamic civilizational narrative. But narratives are never static – they always evolve, changing as the river of history shifts its course. Historically, the most important intellectual and cultural evolution of the West are more recent, like the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Enlightenment of the early 18th century and the artistic, literary and intellectual movement originating in the second half of the 18th century (Romanticism), could not have been possible without Europe’s connection with Islamic thought and other Eastern cultures, and their impact on Europe through Spain, southern France and southern Italy for centuries. “It is highly unlikely that, but for the Muslims (Arabs), modern European civilization would ever have arisen at all” according to Sir Thomas Arnold and Alfred Guillaume – in “The Legacy of Islam” 1997. The distinguished historian, Robert Briffault, in “The Making of Humanity” writes, “It was under the influence of the Arabian and Moorish revival of culture, and not in the 15th century, that the real Renaissance took place in Spain and Italy that was the cradle of the rebirth of Europe.”

The Renaissance marked a new beginning in European civilization, where new thought and culture came into being. The impact of Islamic civilization on Europe laid the foundations for a modern civilization in the West. The question arises as to how the great change in Europe came about. Did modern European Civilization really rise from nothing? It was founded on a major artistic and cultural rebirth, science, philosophy, intellectual and literary currents from the seventh to the sixteenth Muslim centuries and the East. Islamic origins and its culture have had worthy purpose, and we must open up to the world some fair understanding of the richness of Islamic civilization and its tremendous impact on the West. The details of the works of Muslim writers, scientists and artists had been lost to general perception in the Western history, yet the accomplishments of Islamic civil society, from the seventh century on, have flowed into and enriched the Judeo-Christian world. In fact, the three traditions — Christian, Jewish, and Islamic — are inextricably interlinked. The Islamic world gave rise to some of the earliest libraries, universities and hospitals and, at its best, had encouraged ideas of civic tolerance, compassion and empathy that permitted the development of the talents and potentials of all humans, whatever their denominational orientation.

History of civilisation

The eventual discovery of far West Americas at the very end of fifteenth century actually connected the Middle ages of Europe and the East to the beginnings of renaissance in the sixteenth century. In 1492, when Columbus sailed the ocean blue and we had been led to believe, as if Europe had conquered the world. However, what we’ve all totally forgotten (or ignored) was the fact that there were other world powers before the British Empire, before the United States. There were the predominant Chinese and Islamic Civilizations (Arabian, Muslim Spain, Mughal Indian, Persian, Ottoman, Euro-Asian and South East Asian including Indonesia and Malaysia, and most of North Africa) that had lasted much longer and had the greatest influence worldwide than anything Europe or the rest of the world had ever produced.

Tamerlane was the last world-conqueror, although inheritor of Genghis Khan, whose empire ranged from Iran to China to Moscow. After Tamerlane’s sudden death in 1405, his empire fell apart and the modern world in Europe as we know it began to form. Princes under Muslim Kazan (Ural Mountain) Tatars and other Muslim Khanates (like Qasimov, Astra khan and Golden Horde Khanates) in the then Russia or Muscovy began to take control of Khanates’ territories and started to become Czarist Russia. Ivan the Terrible took the city of Kazan in 1552 while China’s accelerated cultural progress had begun to stagnate. Also, Europe’s sea-worthy nations had begun to extract wealth from their overseas conquests. “AFTER TAMERLANE’’ 2008, a book by John Darwin, one of the most preeminent historians, has fabulously balanced a wide-ranging revelation of world history of the past six hundred years. John Darwin is indeed a true star in this context. He has revealed the seeds of the modern world and also makes us understand what fawned today’s world events. The East was Centuries ahead of the West by almost every measure. As Europe foundered in the dark depths of the Middle Ages, China, the Middle East, Muslim Spain, Euro-Asia, South and East Asia flourished, with lively traditions of scholarship, invention, and trade. The Muslim world as a whole was at the forefront of civilization, preserving and further building on Greek and Roman knowledge producing path-breaking works in multiple fields as diverse as mathematics, physics, medicine, astronomy, anthropology, and psychology.

From the 16th Century, Europe started to introduce new art, new politics, new ideas of banking and finance, new philosophy that helped crystallize this new narrative that was rooted in the science and philosophy of the medieval wide-world Islamic civilization, based in centers of learning ranging from Central Asia, South Asia, Middle East to Spain. The Muslims had preserved the knowledge they acquired and advanced from earlier ancient empires (including ancient Greeks, Romans and contributions from Mesopotamia, Sassanid Persia, India and China) and conveyed it to Europe.

Al-Khalili has looked at the important part played by the “translation movement”, a House of Wisdom in Baghdad, which saw much of the wisdom of the earlier civilizations of the Greeks, Romans, Persians and Indians translated into Arabic over a period of 200 years. He sees this not just as a separate process that led to a subsequent “golden age of science”, but as an integral and early part of the Islamic golden age itself.1 The multiplicity of people of faiths who lived harmoniously and collaborated on projects of translation and learning was a hallmark of the Muslim golden age’s tolerance and pluralism.

This cross-fertilization of world of ideas and the bringing together for the first time of a wide range of different scientific traditions from around the world meant that “the scholars of Baghdad, Egypt and Spain had at their disposal a far broader world-view than anyone before them”. The rediscovery of classical texts and contact with earlier civilizations through Muslim scholars (Baghdad to Cordoba, or Damascus to Cairo, Samarkand to New Delhi and Baghdad) led to the birth of European renaissance. A great flowering of human achievement was unleashed. While many historians focus on the Muslim’s material gains in medieval times, they frequently miss out on the Islam’s real purpose and contributions of tolerance, compassion, empathy, global community building and peacemaking. Michael Morgan on page, 136 of “Lost History” says: “By the ninth and tenth centuries, the Jewish intellectual communities and economies of Muslim Spain, in cities like Cordoba, Seville, and Toledo, are at their peak. Not only have Jews risen to hold the second highest political position in the realm, under Hasdai ibn Shaprut working for Caliph Abd Al-Rahman III; they are also producing their own rich literature, music, philosophy, and scientific thought, sometimes independently, sometimes in collaboration with those of other faiths.”

The remarkable innovations of Muslim thinkers such as Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen in some writings) and Abbas Ibn Firnas are startling for their times. In A.D. 875 in Córdoba, at the farthest extent of the Arab Empire in present-day Spain, Ibn Firnas successfully experimented with a wood, silk, and he investigated the mechanics of flight constructing a pair of wings out of feathers on a wooden frame and made the first attempt at flight that was airborne for many minutes and thus anticipating Leonardo da Vinci by some six hundred years. He also constructed a famous planetarium that not only was mechanized – the planets actually revolved – but it simulated such celestial phenomena as thunder and lightning. Ibn Firnas had further experimented in mechanics, time, and, astronomy but, like much of the scientific exploration of the early Muslims such “intellectual heresy” was often lost to hidden history and Lost History: “The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Scientists, Thinkers, and Artists.” (Michael Morgan 2007). The list of Islamic Spain’s and broader golden age Muslim civilizational contributions to the West, in fact, is endless still and cannot be all covered in this brief writing. In addition to Islamic Spain’s contributions in mathematics, economy, medicine, botany, geography, history, and philosophy, al-Andalusia also developed and applied important technological innovations: the windmill and new techniques in the crafts of metalworking, weaving, agriculture and buildings.

Ibn al-Haytham, however, was one who published over 50 books of his works that would eventually be translated into Latin in the thirteenth century. These translations would become readily available to scholars in Italy. For al-Haytham, the world could not be understood philosophically, but it could be measured. Remarkably, he nearly determined the thickness of the earth’s atmosphere and almost articulated the physical concept of gravity. Moreover, he identified the linear quality of light and built an object very much like a camera obscura (the pinhole camera) to help demonstrate it. He correctly described vision occurring when light rays enter the eye and stimulated the optic nerve, the fact that light travels in straight rays, and his famous book Kitab al-Manazir (The Book of Optics) had minor errors. Most importantly, Ibn al-Haytham performed research to arrive at important conclusions. He established and used the scientific method as we know it today, and that is why Western historians called him the first scientist who gave striking examples with diagrams and pictures demonstrating his experiments. It would be more than five centuries before the likes of da Vinci, Galileo, and Newton would replicate and then build upon al-Haytham’s foundational works (Michael Morgan 2007). Renaissance revisionist historians, on the heels of European fear of the Arab Empire, easily rewrote the Renaissance without acknowledging the golden age of Islamic science, culture, and thought (Morgan 2007). Yet, their indelible impression cannot be overlooked despite the fact that centuries have been particularly harsh on Muslim and Hebrew published materials from the Iberian Peninsula of which many had disappeared in the course of medieval conquests, forced conversions and expulsions of Muslims and Jews from Al-Andalusia. (Michael Morgan 2007).

Centuries before European continuing evolution of culture and Renaissance (early, high, and late Middle Ages) men such as da Vinci experimented with light, optics, or even aeronautics, Muslim thinkers across the extensive Muslim-world had developed the foundations of technology that in some instances unfortunately wouldn’t be explored or fulfilled again until the twentieth century. Muslim thinking and innovation throughout the era was, in many ways, a strong foundation of the Renaissance in Europe, via cultural, ambassadorial, and commercial routes across the continents and beginning with Spain and Italy. Spain and Italy were particularly receptive to such thinking as they entered into the period of classical revival that looked to the knowledge of the Roman and the Greeks for inspiration. The Renaissance throughout Europe would closely resemble Spain and Italy both, as they would ultimately prove to be in the ideal geographical position to welcome the knowhow from Muslim culture.

History of Science and Civilisation 2

The idea of progress, a new way of thinking, associated with the rise of modernism in Europe, derived from a series of historical developments beginning at least as far back as the High Middle Ages (1000AD-1300 AD). Modernism is both a philosophy and a way of life. It is a multi-faceted reality, connected with profound changes in technology, habitation, economy, politics, and culture that have further altered all aspects of human life especially over the last few hundred years.

The philosophy of modernism and secular progress arose further as a consequence of a series of revolutions in thought and social organization, beginning with the Renaissance (1500 AD), and proceeding through the Age of Exploration and Colonization (1500 – 1800 AD), the Scientific Revolution (1600 – 1700 AD), the Age of Enlightenment (1650 – 1800 AD), the emergence of capitalism and nation states, and culminating in the 1st and 2nd Industrial Revolutions (1750 –1900 AD). Contrary to the “Eurocentric” descriptions of the emergence of modernity, it was actually a global phenomenon to begin with, involving the contributions of nations and cultures from around the world. Modernism first blossomed in Western Europe, but its origins were global nevertheless and its consequent effects have been also global.

In the centuries preceding the rise of modernity, networks of commercial and information exchange evolved and spread across the Eastern Hemisphere, from China, to India, to the Islamic Empire (including Islamic Spain), Africa, and Europe. The increasing rate of innovation came with increased sharing, cross fertilization of ideas with the East, and in general, a building up of economic and informational reciprocities. Also, due to a widening sphere of markets across the continents. The start of European modernity in the High and late Middle Ages (1000 AD to 1300/1300-1400 AD) was most certainly triggered by Islamic global civilization and its 800-year history in Spain. At the beginning of this period, in addition to the Muslim World, the other important centers of new ideas and inventions were China, India, rather than Europe. It was during Europe’s dark Ages that a transformation in thinking began, connected with the Golden Age of Islam, rise of individual freedom and the rediscovery of Aristotle through Islamic civilization, which would catapult Europe ahead of the East, a few centuries later.

End Notes

1 Al-Khalili Jim,” The House of Wisdom” Golden Age of Learning in the Arab-speaking World, Qantara.de- 02/09/2011