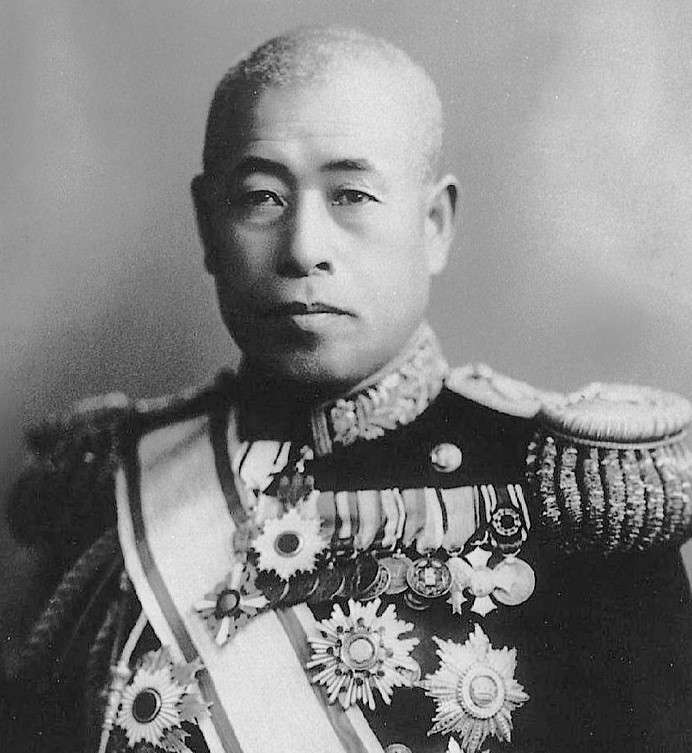

Admiral of the Fleet Isoroku Yamamoto (1884-1943) is among the famous Japanese admirals of World War II. He has the distinction of being the architect of the attack on Pearl Harbour, defeat at Battle of Midway by inferior forces and his assassination over Bougainville while travelling by air.2 He is considered among those visionary admirals who realised the changing nature of naval warfare from primacy of battleships to effectiveness of maritime air power.3 Although he had significant experience of naval warfare, Midway was the only battle when he actually commanded the Combined Japanese Fleet.4 Due to ill planned operation which resulted in dispersion of the force, the Japanese suffered their first defeat at sea since the sixteen century.5 It was a turning point for war in the Pacific and its tremors were felt in Europe by Allied and Axis forces alike. In order to analyse the operational performance of Yamamoto in the Battle of Midway, Australian Defence Leadership Framework6 and Operational Leadership model by Dr. Milan Vego7 were considered. However, the leadership model presented by Milan Vego has been used for analysis as it is principally devised for naval environment.8 The naval operational leadership framework is based on personality traits, professional knowledge, command style, decisiveness and operational tenets.9 Various parameters of leadership model have been explained and operational performance of Yamamoto has been evaluated in ensuing paragraphs. The analysis of operational leadership of Yamamoto reveals that he possessed all the necessary qualities required for a successful operational leader but he failed on informational decisions and operational tenets during the Battle of Midway.

Personality traits include character, intellect, creativity and boldness.10 Yamamoto possessed admirable character, high intellect and creativity. He was highly respected as fleet commander by friends and enemies. A testimony of his creativity was the naval sides of Japanese invasion of Philippines, Malaya, and Netherland East Indies which were brilliantly planned and executed.11 He was a bold leader with courage to oppose the idea of war with US even in the face of danger to his life. He wrote to one of his friend, ‘Because I have seen the motor industry in Detroit and the oilfields of Texas, I know Japan has no chance if she goes to war with America, or if she starts to compete in building warships’.12

He was also known for his selflessness. One of his staff members remembers that: ‘…if something he undertook went off well his subordinates got the credit for it. If it didn’t go well, it was his responsibility’.13 The strength of the character was again tested after defeat at Midway when he said to his tearful staff, ‘I will apologise to the emperor myself. It is all my fault. Do not speak badly for the carrier force’.14 Hence Yamamoto passed the test of personality traits based on high intellect which was acknowledged by his friends and foes, his moral courage to accept defeat and boldness to convey his opinion despite heavy opposition.

Professional knowledge is another element of operational leadership which encompasses theory and practice of operational art and naval diplomacy.15

Yamamoto had significant experience at tactical, operational and strategic level. In 1905, as an ensign, he participated in Battle of Japan Sea onboard NISSHIN and seriously wounded in action. His other important duties included Second in Command of Kasumigaura Aviation Corps (1924), Captain of cruiser ISUZU (1928), Captain of aircraft carrier AKAGI (1928) and Commander of First Carrier Division onboard AKAGI (1933) prior assuming duties of Commander in Chief of the Combined Fleet (1939).16 Apart from his professional acumen, he was also known for his comprehensive knowledge of the enemy, primarily because of his tours to US in different capacities. He had studied in Harvard University (1919-21) which gave him a fair idea of US at grass root level.17 He also served as Naval Attaché in Washington (1926-28) which gave him an insight into US diplomatic and policy circles. Additionally he had the chance to participate in strategic level talks as a Japanese delegate (1930, 34) in the Naval Disarmament Conference in London. All these professional and diplomatic experiences enabled him to understand the enemy well. So in September 1940 when Japan signed the Tripartite Treaty of Alliance with Germany and Italy, he termed it to be ‘quite irrational’. He termed Japan as ‘very foolish as she will be shocked to find what America can do to threaten her economically’. This proved accurate as soon as US began to impose embargoes on supplies of raw material to Japan which became gradually severe as oil embargo was also placed.18 Therefore Yamamoto possessed sufficient knowledge and experience required for naval operational leadership.

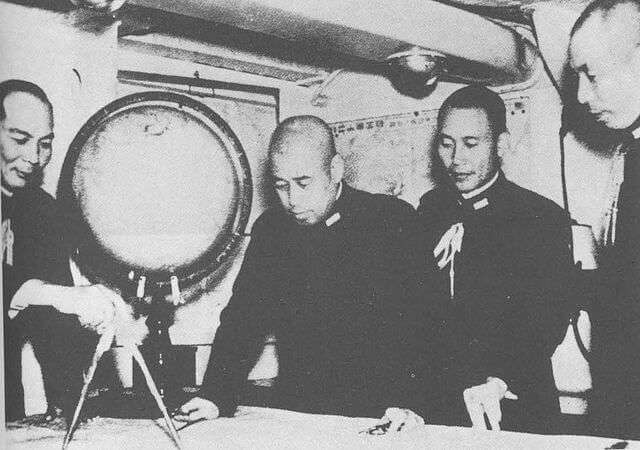

Another important element of naval operational leadership is command style that depends upon the personality of the commander, which can be either leadership by example or directive or a combination of both.19 An example of the directive command can be found during planning phases of attack on Pearl Harbour. Admiral Genda, who took the leading part in the discussions, recalled that:

…He [allowed] those in charge [of planning to] do it the way they pleased. If someone asked for six aircraft carriers, they got six; if they needed so many aircraft, then they got so many. If some wanted to approach from the north, he said O.K., you approach from north. In these matters lay the secret of his greatness as a leader…20

Other than directive command, he also lead by example when he joined poor pilots on flying training in order to boost their morale. Hence it can be argued that command style of Yamamoto encompassed directive command as well as lead by example.

The next and one of the most important aspects of naval operational leadership is decisiveness. It is based on three kinds of decisions which include organizational, informational and operational. Yamamoto performed well in organizational and operational domains rather than informational decisions. ‘Organizational decisions are aimed at establishing and maintaining sound command organization and determining command relationships and force subordination’.21 In 1923, Yamamoto became the Executive Officer at the Kasimaguara Naval Air Training Centre. He convinced the trainee pilots that in next war the naval aviation will play a major role. This was a key factor in the superiority of Japanese Naval Aviators.22 Similarly, in 1932, he became the in charge of Naval Aviation Technical Department and played a pivotal role in development of carrier borne fighter Zero with the close cooperation with aircraft manufacturer Mitsubishi Ltd. It is considered as the best aircraft held by either side during war with US. Although he faced strong opposition by supporters of battle ship faction in the navy, he continued to improve naval aviation.23

‘Informational decisions are intended to facilitate access to information resources required to support sound decision making’.24 This seemed to be a grey area. The secrecy and element of surprise used in planning of Pearl Harbour attack were not emphasized during planning for Midway. The details of plan were known to many officers. The messages containing the details of plan were not transmitted with highest crypto codes; hence US intelligence was able to decode these messages. Details of the plan were known to US forces in the area. The major problem was inability of Japanese intelligence to locate US aircraft carriers and their future plans. On the other hand, tactical plan for employment of scouting resources for surveillance and reconnaissance was not effective. It was planned to carryout reconnaissance of Pearl Harbour using sea planes after refuelling from Japanese submarine at French Frigate Shoal. But upon arrival in the area, submarine found two American sea plane tenders and sea planes in the area.25 So the reconnaissance of Pearl Harbour was cancelled without locating aircraft carriers. Additionally, a submarine screen was also planned between Pearl Harbour and Midway to forewarn Japanese navy when Pacific fleet sailed from Pearl Harbour. However submarines reached in respective stations after the Pacific fleet transit in the area. Resultantly, Yamamoto believed that Pacific Fleet was still in Pearl Harbour. Hence, Yamamoto failed in the aspects of informational decisions due to inadequate security of available information as well as insufficient access to enemy information and order of battle.

Another factor of decisiveness is operational decisions. These are either to amend various aspects of pre-planned operations or to modify decisions made by subordinate commanders.26 In this domain, he performed adequately. In Pearl Harbour attack, the carrier force turned back after initial attack on Pacific Fleet and did not conduct further strike to destroy dockyard, fuel reserves and other strategic infrastructure. Yamamoto was suggested to task the carrier force for subsequent strikes; however, he believed in the judgement of on scene commander and did not order any further strike. Whereas in Battle of Midway, when all the four carriers were lost, although he had eleven battle ships compared to none available with US, he did not risk remaining force and dashed home.27 So it can be argued that Yamamoto took prudent operational decisions which were based on the primacy of judgement of on scene commander either in Pearl Harbour or Midway. Hence in domain of decisiveness, it can be said that Yamamoto performed well in organizational and operational decisions whereas his performance in informational decisions was not satisfactory.

Milan Vego identifies operational tenets to be the most important element of operational leadership. These have similarities to principal of war but can be understood as primacy of policy, interplay of principles of war, and balancing ways, means and ends.28 Analysis of Battle of Midway confirms that Yamamoto performance lacked in certain aspects of this element. He believed in the absolute primacy of policy over his own thoughts. On 1 December 1941 when the Japanese government made its final decision about war with US, although he was not in favour of this idea, he vowed to do his duty. In a letter to his friend he said, ‘…I [am] determined to do my duty, which [is] completely opposite to my personal convictions…’.29 As he failed to convince his colleagues about the dangerous prospects of war with US he put all his energies to fight it to the best of his abilities. He also made it clear to his superiors about the dangers of a long and protracted war. ‘If you force me to fight, I will show some real action for the first six months or a year. But if the fighting continues for two or three years I do not have any confidence whatsoever’.30

Yamamoto violated the principles of war by complex manoeuvring of large forces to accomplish multiple objectives which ultimately led to disaster. He was pursuing two different objectives – first was to attack and seize Midway atoll and second, to draw out the Pacific Fleet for decisive battle. This was accompanied with diversionary attack on Aleutians. It is considered that both the objectives were incompatible with each other. Another factor is allocation of substantial forces for accomplishment of secondary tasks. At Midway, the sector of main effort was around Midway atoll, while the sector of secondary effort was Aleutians, but large amount of forces were allocated to secondary effort, which could have strengthened their main effort at Midway.31 All the forces were dispersed in an area, outside of the mutual assistance range. Particularly, four attack carriers were steaming 300 NM ahead of battleship force under direct command of Yamamoto. Japanese force was already handicapped due to non-availability of radar which restricted their surveillance capability.32 The forces were outside the communication range due to imposition of radio silence. Another reason for the failure of Yamamoto was his predicament of application of new concept of carrier strike force with old fleet. The overall fleet was designed on the concept of a defensive strategy of ‘Gradual Attrition’.33 This means that fleet was not primarily designed for fight with new concept. Although, Japanese Navy concept of torpedo force and shore based aviation proved effective, however, failure to use submarine for commerce raiding and protection of shipping further contributed to defeat.34 Although US Navy knew plans of Japanese attack, if Yamamoto had not violated the principles of mass, objectives and economy of effort, the outcome of the battle could have been different.

In conclusion, history is full of leaders with outstanding military careers during peace time and comprehensive defeat in war. Yamamoto is also one of them. He was a talented and visionary admiral which had been wounded in action as early as an ensign in the Imperial Japanese Navy. He had a distinguished career with important command and staff appointments at strategic, operational and tactical level. Thorough understanding of the enemy due to repeated interaction at academic and diplomatic level enabled him to foresee the outcome of the war with US. But like professional military officers, he believed in primacy of policy and put-up his best efforts to fight, especially in the raising of naval aviation. Despite initial successes in South West Pacific campaign, historical defeat at Battle of Midway turned the tide. Analysis of the operational performance of Yamamoto confers that he had all the qualities required for successful naval operational commander but his failure in informational decisions and application of operational tenets led to disaster at Midway.

Bibliography

Adams, Bruce. Reveille. Sydney, NSW: The Returned and Services League of Australia, 1970.

Agawa, Hiroyuki. Kodansha International Ltd: Tokyo, 1982.

Barnett, Correlate Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: The Praetorian Press, 2012.

Field, James A. Proceedings. Annapolis, Maryland: U.S. Naval Institute, 1949.

Koda, Yoji. Naval War College Review. Newport, Rhode Island: Naval War College, 1993.

Kaczynski, Andre G. Asian Profile. Burnaby, BC: Asian Research Service, 1982.

Potter, John Deane. Yamamoto The Man Who Menaced America. New York: Kinney Service Company,1971.

Shultz, Linda K.A Comparative Analysis of the Operational Leadership of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto and Admiral Chester W Nimitz at the Battle of Midway. Newport, Rhode Island: Naval War College, 1997.

Turner, L C F. Army Journal, 1973.

Vego, Milan. Joint Operational Warfare. Newport, Rhode Island: Naval War College,2009.

Vego, Milan. Operational Warfare at Sea. London: Rutledge, 2009.

End Notes

2The transport aircraft carrying Yamamoto was shot down by P-38 aircraft near Kahili in Bougainville on 18 April 1943 when he was inspecting forward bases in South West Pacific. US intelligence had intercepted and deciphered his inspection plan and special aircraft were tasked to intercept his aircraft. ‘Isoroku Yamamoto,’ assessed May 12, 2013, http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Yamamoto.html.

3Milan. Vego, ‘Operational Leadership’. In Operational Warfare at Sea. (London: Rutledge, 2009), 9.

4Battle of Midway was fought 4-6 Jun 1942. Japanese losses included four fast carriers, 253 aircraft, one cruiser sunk and 3500 men were killed which included 100 pilots. Milan. Vego, Joint Operational Warfare. Vol. 1, (Newport, Rhode Island: Naval War College, 2009), II-3.

5Vego, Joint Operational Warfare, II-3.

6‘The Defence Leadership Framework,’ assessed May 12, 2013, http://www.defence.gov.au/publications/DLFBooklet.pdf

7Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 184.

8Naval environment is particularly different from air and ground environment. In naval environment generally more freedom of manoeuvre and endurance is available than air and ground environment. Since naval forces take a long time for building up, training and achieving operational proficiency, outcome of tactical level battles influence the outcome of war at strategic level. Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 184.

9Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 184-201.

10Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 185.

11Vego, Joint Operational Warfare, II-3.

12Correlli. Barnett, ‘The Reluctant Gambler Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’. In The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill. (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: The Praetorian Press, 2012.), 163.

13Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 167.

14Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 171.

15Skills required for naval diplomacy include ‘a broad knowledge of foreign policy, diplomacy, geopolitics, the international economy, ethnicity, religions, and other issues that shape the situation in a given theatre’. Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 189.

16Hiroyuki. Agawa, ‘The Reluctant Admiral Yamamoto and the Imperial Navy’. (Kodansha International Ltd: Tokyo, 1982.), Chronology of events.

17Agawa, The Reluctant Admiral Yamamoto and the Imperial Navy, 73.

18Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 168.

19Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 189.

20Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 169.

21Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 191.

22Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 164.

23Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 166.

24Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 192.

25Fuchida and Okumiya, Yamamoto The Man who Planned Pearl Harbour, (New York: McGraw Hill Publishing, 1990), 162.

26Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 192.

27Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 171.

28Operational tenants are as follow: ‘The unconditional acceptance of absolute primacy of policy and strategy, firm and unwavering focus on the objective, balancing ends, ways and means, focus on the enemy centre of gravity, indirect approach, protection of friendly centre of gravity, obtaining and maintaining freedom to act, exercising the initiative, taking high but prudent risks, selecting a proper sector of main effort, concentration in the sector of main effort, application of overwhelming power at decisive place and time, acting unpredictably and avoiding patterns, creativeness and jointness’. Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea, 195.

29Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 169.

30Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 168.

31Vego, Joint Operational Warfare, IX-28.

32Barnett, The Lords of War from Lincoln to Churchill, 171.

33Japanese Strategy was aimed to destroy already deployed small US force in Asian waters in early phase of war and thereafter to destroy main US fleet in Japanese waters. Yoji. Koda, ‘A Commander’s Dilemma Admiral Yamamoto and the Gradual Attrition Strategy’. In Naval War College Review. Vol. XLVI, No.4, Sequence 344, (Newport, Rhode Island: Naval War College, 1993), 64.

34Yoji, A Commander’s Dilemma Admiral Yamamoto and the Gradual Attrition Strategy, 63-74.