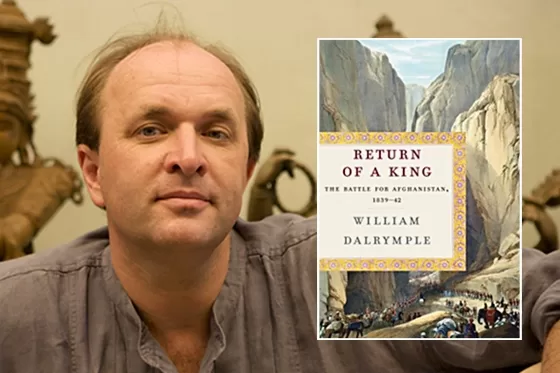

William Dalrymple’s latest work Return of a King is a fascinating account of First Anglo-Afghan War of 1939-42. Dalrymple is a well known historian of India and his previous works City of Djinns, White Mughals and The Last Mughal are based on his extensive research spanning several years while living in India. One crucial factor that differentiates Dalrymple from other English language historians is his use of local sources mainly in Urdu and Persian. In telling the story of the First Anglo-Afghan War, he also used Afghan sources that are now available to English language readers for the first time. However, all Afghan and Indian sources used by Dalrymple are not reliable and some are polemics that freely mix fantasy with facts. Dalrymple sheds some light on two fascinating characters; Mohan Lal and Shahamat Ali. These two natives were first students of English at Delhi College and in an all British cast, the two played a very important role as native political assistants to British.

In summary, by 1839, Dost Muhammad Khan had established himself as ruler of Afghanistan after annihilating other contenders. A former ruler, Shah Shuja was living in a comfortable exile in Ludhiana as British pensioner and Maharaja Ranjit Singh was ruling Punjab that included Peshawar; the former winter capital of Afghan rulers. British fearful of Russian drive cobbled a plan involving British, Shah Shuja and Ranjit Singh. British will help Shah Shuja to regain his throne with the help of Ranjit. Shuja will get his throne, British will get a friendly ruler who will keep Russians out and Ranjit will keep Peshawar as Shuja will renounce his claim over the territory conquered by Sikhs. This was the genesis of First Anglo-Afghan War. Wily ruler of Lahore was the shrewdest of the three players not allowing the army to take the shortest route that will go through his own territory. Instead, army had to go through the desolate areas of Sindh, Baluchistan and over treacherous Bolan Pass to southern Afghanistan. The journey alone and not any battle devastated the army. Shah Shuja was easily installed at Kabul by British and Indian bayonets and Dost Muhammad changed place with Shah Shuja and lived in same quarters in Ludhiana as pensioner with his slaves and concubines. After a year and a half of partying and affairs in Kabul, British cut subsidies to border tribes into half to decrease expenses, the tribes closed passes, annihilated small force and large camp followers, British sent an army of vengeance to spank Afghans and returned to India, Shah Shuja was murdered, Dost Muhammad came back, repeated the previous act of chopping some rebellious heads and other body parts to become the top dog again and the cycle was completed.

Dalrymple’s story telling style providing extensive details may be boring to ordinary readers but for those interested in history it is pure delight. Dramatis Personae segment alone runs seventeen pages. If ordinary reader overcomes this hurdle then he will enjoy the five hundred page story of a fascinating chapter of British Empire.

Afghans were not just bystanders but active participants in the game of intrigue to further their own interests. Dalrymple provides some details of the Afghan side of the story. To understand the complexities from Afghan perspective, correspondence of Amir Dost Muhammad Khan with three powers in 1836 provides a window to modus operandi of Afghan power players (this is quoted by Mohan Lal; a direct participant with first hand information). This is a classic example of these power plays and how desperately Afghan rulers tried to maintain their independence in extremely difficult situations by playing one power against the other. Dost wrote a letter to Governor General Lord Auckland stating, “I hope your Lordship will consider me and my country as your own, and favor me often with the receipt of your friendly letters. Whatever directions your Lordship may be pleased to issue for the administration of this country, I will act accordingly”. To Shah of Persia, Dost wrote, ‘the chiefs of my family were sincerely attached to the exalted and royal house of your Majesty, I too, deem myself one of the devoted adherents of that royal race; and considering this country as belonging to the kingdom of Persia’. At the same time, he sent a letter to Czar of Russia stating that ‘since Mahomed Shah, the centre of the faith, had closely connected himself with his Imperial power, desiring the advantage of such alliance, that he also being a Mahomedan, was desirous to follow his example, and to attach himself to his Majesty’. In January 1857, Dost Muhammad signed a treaty with British in Peshawar and said that if he had the power, he would fight the unbelievers but as he could not do it therefore, ‘I must cling to the British to save me from the cursed Persians’.

First Anglo-Afghan War was the result of several complex factors. Underlying fear was that Afghanistan and Persia could become the staging ground for Russian efforts to undermine East India Company’s hold on India. This war was just one act of a much larger drama on the world stage what was called ‘Great Game’ by British and ‘Tournament of Shadows’ by Russians.

Many British characters in Dalrymple’s account had long association with India and in many cases several family members were involved in the expansion of the empire. One of the defenders of Jalalabad garrison was a gunner Augustus Abbott. He survived the Afghan cauldron and rose to the rank of Major General. His brother Frederick Abbott (later Major General) of Bengal Engineers was chief engineer in the same campaign. Third brother Saunders Abbott also served in Bengal army, fought in Anglo-Sikh wars and served under Henry Lawrence in Punjab. Fourth brother Keith Abbott was on the diplomatic playing field of the Great Game and during the time of First Anglo-Afghan war was consul at Tehran and later at Tabriz. However, the most famous was General James Abbott. James was also a player in the Great Game and while his two brothers were in Afghanistan and one in Persia, he was travelling in the Khanate of Khiva. Later, he became the young protégé of Henry Lawrence, in charge of Hazara district where he earned the love and respect of local population. The town of Abbottabad, where Osama bin Laden was killed was founded by him.

Head of Shah Shuja’s contingent Colonel (later General) Abraham Roberts spent fifty years in India and his son General Frederick Roberts spent forty four years in India. Frederick followed his father’s footsteps and commanded Kurram Field Force of Indian and British troops in Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1878-80. He became famous for his march from Kabul to Kandahar and later titled Baron Roberts of Kandahar. Frederick won Victoria Cross (VC) in Indian Mutiny and his son also named Frederick won a post-humous VC in Boer War.

Three Broadfoot brothers served in Afghanistan. Lieutenant William Broadfoot (Bengal European Regiment) served in the forward post of Bamyan and improved many passes. He was Alexander Burn’s military secretary and killed along with Burns during attack on the residency. Lieutenant James Broadfoot (Engineers) worked on preparation of advance of the Army of Indus and later wrote an authoritative account of Ghilzai tribes. He travelled in disguise with a Lohani merchant caravan from Ghazni to Dera Ismail Khan through Gomal pass and sketched the area. He was killed in action in November 1840 at Parwan Darrah along with other officers when troopers of 2nd Bengal Light Cavalry bolted. Third brother Captain (later Major) George Broadfoot (34th Madras Native Infantry) was commander of the escort that brought Shah Shuja’s family to Afghanistan. He later converted his escort into sappers and commanded this diverse contingent consisting of Hindustanis, Gurkhas and Afghans and was among the defenders of Jalalabad garrison. George was an excellent swordsman and locals believed that the ghosts of his two slain brothers added extra power to George’s sword cuts. He was killed in action three years later in Second Anglo-Sikh war at Ferozshah.

Captain Robert Warburton’s love affair and later marriage with Shah Jahan Begum is the romantic chapter of the otherwise sanguine first Anglo-Afghan encounter. The child of this union was Robert Warburton. Father was born in Ireland and buried in Peshawar while son was born in a Ghilzai fort in Afghanistan when his mother was on the run and buried in Brampton cemetery. Dalrymple mistakenly writes that Warburton commanded Frontier Force. Punjab Irregular Frontier Force (nick named PIFFERS) consisted of infantry and cavalry regiments and artillery batteries that kept internal peace in newly acquired territories in Punjab. It was commanded by regular army officers. Paramilitary Frontier Scouts were raised to maintain peace in tribal territories. Warburton raised Khyber Jejailchis (later Khyber Rifles) to maintain peace in Khyber tribal agency where he was political agent.

Dalrymple asserts that those regiments that served in Afghanistan mutinied in 1857 because their officers deserted soldiers. There is no evidence to support this assertion. In general, set back of First Anglo-Afghan War had an impact on Indian army as the myth of British invincibility was shattered and affected morale of soldiers. However, mutiny occurred seventeen years after the Anglo-Afghan War. Poor senior military leadership was responsible for many humiliating encounters. In such circumstances, it is not unusual that morale of officers and men is a casualty. There were cases of both British and Indian soldiers shying away from the battle and in some cases behavior of officers was also shameful. However, overall officers performed to the best of their abilities. On the other hand, in many cases Indian soldiers bolted leaving their officers on the field.

Large part of army of Indus had already left Afghanistan long before the Afghans rose against British and Shah Shuja. Disaster only struck the force that retreated from Kabul. This force consisted of 44th Foot of British army, 1st Bengal European Infantry of Indian army, four infantry regiments of Bengal native infantry (2nd, 27th, 37th, & 48th) and one Bengal Light Cavalry (2nd). Total combatants included 690 British, 2800 Indian soldiers and 12’000 non-combatant camp followers including women and children.

1857 mutiny was a general uprising of Bengal army while Bombay and Madras armies in general remained loyal. Large number of Bengal army regiments mutinied regardless of their service in First Anglo-Afghan War. Of the ten Bengal cavalry regiments seven mutinied and three disarmed. Of the seventy four infantry regiments of Bengal army, forty seven mutinied and remainder twenty seven either disarmed or disbanded. Among those regiments that were part of the Kabul garrison, 2nd Bengal Light Cavalry mutinied at Cawnpore, 2nd Bengal Native Infantry was disarmed at Barrackpore, 27th was disarmed at Peshawar, only part of the 37th mutinied at Benaras and similarly only part of the 48th mutinied at Lucknow.

Major Agha Amin’s encyclopedic work based on relevant material on 1857 mutiny provides many interesting details of the military aspect of the upheaval. 2nd Bengal Light Cavalry had an interesting history. Major General Shahid Hamid in his work on Indian cavalry titled So They Rode and Fought provides little known information that it was raised in 1787 as Kandahar Horse by Nawab Wazir of Oudh from Kandaharis settled in Lucknow. In 1796, it became 2nd Bengal Light Cavalry. In 1841, two squadrons of the regiment fled when confronted by a small body of Afghan horsemen at Parwan Darrah leaving their officers on the field. The exact cause was never established but Agha Amin’s suggestion about the origin of troopers of the regiment which were mainly Afghans of Kandahar origin is the most likely explanation. These Kandaharis who had settled in Lucknow did not want to confront their ethnic kin though separated by a time span of sixty years. The outraged commander disbanded the whole regiment. A new 11th Light Cavalry was raised and all officers of 2nd transferred to 11th Light Cavalry. In 1850, 11th Cavalry fought gallantly in Multan and one of the old officers captured the Sikh standard. This performance was rewarded by renaming 11th Cavalry to its old number of 2nd Light Cavalry.

Dalrymple connects past with the present in his usual style. However, no two conflicts are same and causes and consequences of every conflict are unique. East India Company had no interest in a project that didn’t generate revenue and in 1839 First Anglo-Afghan War was the result of Russophobia. One of the key architects of the policy Lord Palmerston declared that the purpose was not to make Afghanistan a British province but install a client ruler that could join hands with British to keep Russians at bay. The staggering cost of three million sterling pounds almost bankrupt Indian treasury. Initial force consisted of 21’000 combatants and 38’000 camp followers. Large part of the military force was already withdrawn to India prior to uprising and at the time of general revolt, in addition to a small garrison in Kandahar there were only 4500 combat troops and 14’000 camp followers that retreated from Kabul. In fact, despite humiliating defeat of this war, overall British objectives were secured for the next one hundred years. The country remained a buffer even long after British had gone from India. Amir Dost Muhammad had learned his own lesson and in 1857 rebellion of Indian army when he could have easily recaptured his lost territories including the prize of Peshawar, he didn’t venture beyond his own borders. Foreign relations of Afghanistan remained subservient to British for the next eighty years for a small subsidy paid to Afghan rulers.

It is too simplistic to assume that somehow if world leaders read the history, they will avoid blunders. U.S. involvement in Afghanistan was the direct result of September 11 attacks and presence of Osama Bin Laden in Afghanistan. If Bin Laden was in Timbuktu, U.S. forces would be heading there and not Afghanistan. Once started, each conflict evolves and after a while original spark that started the fire becomes irrelevant.

Dalrymple is a master story teller and we owe him thanks for providing a masterpiece narrative of a forgotten chapter of history. We hope that such works stimulate interest of local historians to utilize rich research materials stacked at their doorsteps.