Introduction

Military forces are an important element of national power. Their role in national domains depends upon the history and government structures of the nation. In some states where military dictators rule the country, the armed forces have strict control on the affairs of the state. On the other hand, in most democratic states military forces are not directly involved in execution of state affairs, however, they have a strong influence on national policies, especially on national security and sometimes foreign policy as well. Since independence, security environment coupled with military rule in Pakistan has transformed armed forces as an important part of society. Other than defence of nation against armed attack, military forces have been involved in counter insurgency, disaster relief, humanitarian assistance, nation building, census and election duties and other constabulary and benign tasks. The primacy of military forces in national domain is oftenly criticised by various domestic and international groups due to various agendas. This article explains the evolution of whole of government approach in various developed countries and explains the evolving role of military forces in the Whole of Government Approach. Thereafter, various impediments in operationalizing whole of the government approach have been discussed. Finally it has been deliberated that culture is the most significant impediment with measures to resolve the cultural differences for success of any WGA. Based on the experiences of various countries, way forward for Pakistan have also been discussed. Primarily the literature regarding Australia has been used for the study because Australia and Pakistan both are commonwealth states. Both have British heritage and government structure and both are heavily influenced by United States.

Evolution of Whole of Government Approach

Whole of Government Approach (WGA) has gained significance in recent years. In post-Cold War era, the security environment transformed from military to complex mosaic of trans-national, national, non-state actors playing their part in terrorism, smuggling, human trafficking, narcotics and various non-traditional threats to national security.2 Globalization, improvement in information technology, means of transportation and media has changed the contemporary conflict into a complex, multi-dimensional and dynamic issue. ‘The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have revealed the limitations of traditional military and diplomatic interventions’.3 Similarly the experiences of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo have also highlighted the insufficiency of military responses in multi-dimensional conflicts. The political and military planners have realized that short term and ad hoc actions cannot guarantee the long term solution to issues faced in modern world. This has led to the development of Whole of Government Approach. This approach is based on the concept that all elements of national power (e.g. diplomatic, information, military and economic) are necessary for solution to any problem. The combination of these elements required for solution of any problem varies for different operations.

The terms, Inter- Agency, Whole of Government, and Comprehensive Approach all refer to similar approaches to the solution of complex problems. These are result of efforts made to: ‘encourage collaboration between departments and agencies – challenging the traditional silos of policy-making that have characterised large, functionally specialised and differentiated bureaucracies’.4 These approaches require effective civil-military relations to solve the problems.5 The combination of military and civilian elements of national powers enables to address the root cause of the problems and presents enduring solutions.6 In Australian context, the term Whole-of-Government is coined whereas in the United Kingdom, its equivalent ‘Joined-up Government’7 was initiated by Prime Minister Tony Blair. On the similar lines, United States have come up with the idea of Smart Power8 and NATO has adopted concept of Comprehensive Operations.9

There are many definitions used for the term Whole of the Government Approach. A concise definition is: ‘collaboration between all relevant government agencies to achieve better outcomes for clients’.10 Another definition provided by the Australian Government Management Advisory Committee (2004) is:

Whole of government denotes public service agencies working across portfolio boundaries to achieve a shared goal and an integrated government response to particular issues. Approaches can be formal and informal. They can focus on policy development, program management and service delivery.

Although WGA is being applied in various issues faced by modern governments, for the purpose of the study, because of involvement of civil and military agencies, the definition provided by OECD Fragile State Group is relevant:

One where a government actively uses formal and/or informal networks across the different agencies within that government to coordinate the design and implementation of the range of interventions that the government’s agencies will be making in order to increase the effectiveness of those interventions in achieving the desired objectives.11

Australian Defence Force Publication 5.0.1 (Joint Military Appreciation Process) recognises that all elements of national power are necessary for implementation of national strategy in contemporary operations. The combination of these elements required for solution of any problem varies for different operations. Generally some elements can be ‘supported’ whereas others could be ‘supporting’. It means that for some operations military element may not be main effort for solution of the problem however, it can be a key enabler or supporting element to achieve the desired end state.12 The roles, participation and contribution by different departments are not static and stable; they change at various stages of the operations.13 For example in a counter insurgency operations, the police and armed forces have major role to play in surgical operations and other departments have minimum role to play. Contrarily in stabilization phase, the role of the development agencies is more pronounced because they have to speed up their efforts to increase the benefits at grass root levels while role of police and armed forces is restricted to maintaining law and order.

Application of Whole of Government Approach

The recent conflicts of Iraq and Afghanistan have highlight that along the political and security nexus, the involvement of foreign affairs, defence and development agencies is paramount in contemporary Whole of the Government Approaches. The other important departments include police, judiciary and treasury. However, in order to avoid delays in coordination of large number of departments, initially the key departments are involved whereas other departments are involved on requirement basis.14

Other than combat operations, the Whole of Government Approach is necessary because natural disasters and other calamities occur in any nation where different government agencies are responsible for various jobs. Military forces are often the first ones to respond to such calamities. These agencies have restrictive and sometimes overlapping responsibilities. The conflicting interests of various agencies lead to incoherent responses to these disasters. The whole of government approach is necessary to avoid wastage of resources as well as duplication of efforts.15 The WGA is used in many initiatives requiring multi agency cooperation. Crime prevention, border protection, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief are few of such initiatives. The military forces may not be part of all such initiatives. However, this study is concerned with all kind of WGA operations.

Whole of Government Approach is not restricted to government agencies only. As the name implies, it is considered that WGA is only concerned with government departments, however Institute of Public Administration Australia, New South Wales believe that according to the strategic objectives, issue or area concerned, the approach may require involvement of non-government entities.16 This is due to the fact that in today’s globalized world, all the required knowledge and expertise may not be held by government departments and unilateral solution of one problem may bring subsequent problems to other departments. Although governments have resources, some non-government entities may offer significant resources and expertise to solve the concerned problem. Moreover, the public is interested in solution of the problems regardless of mandates of different departments.17 The challenge in WGA is to know when to involve other government and nongovernmental participants and under what terms and conditions.18 However, this study focuses on initiatives involving government agencies at national level only.

Hence WGA is a philosophy to address a crises or conflict. It enables all the contributing actors to harmonize their efforts and resources to achieve the common goal. It can also be described as an attempt to have coherence in thinking from strategic to tactical level and achieve practical cooperation among diplomacy and politics, economy, armed forces and civil society.19 The effective implementation of WGA requires all participants to put in dedicated efforts with honesty to solve the common problem. It is paramount to accord due regard to individual participants roles, mandates, strengths and autonomy.20

Challenges in Whole of Government Approach

Despite all the benefits of WGA on theoretical and practical level, it is difficult to achieve whole of government approach due to various reasons. The case studies of various operations show that lack of combined planning process, departmentalism, organization cultures, resources and system impediments are the major obstacles in WGA.21 The successful implementation of whole of government approach requires a dialogue between military and non-military contributors. ‘Such an implementation requires networking and coordination as opposed to the need to coordinate others – it is to the same extent civilian-civilian as well as civilian-military coordination’.22 This approach cannot be instantaneously started, it needs to be started before any conflict or crises begin.23

Lack of Participation in Planning Process

The obstacles start with lack of participation in planning process. In any WGA, various agencies are joined because of their roles in the crises. Generally all the participants have different perception of problem and diverse solutions to the same problem. They also have different vision and measurement of success. ‘It is considered that civilian agencies lack the same level of vertical integration since they do not have appropriate centres of operative planning the way they exist at the level of the army’.24 Military forces have structured thought process which helps to frame the problem and deliberate various options. Often non-military participants complain that they are not included in the planning process from the beginning. Absence of various stakeholders in the planning phase leads to lack of coordination in execution phase. The Swedish Joint Preparation Process is a good example to address the issue. In this case all the stakeholders are involved in the planning process from the beginning to harmonize their activities throughout the operation.25 Absence of common strategic vision has also been observed which results in wastage of resources, inefficiency and impermanence of achieved results.26 A joint policy statement is necessary so that all the participants and stakeholders are at the same grid.27 Definition and measurement of success is another obstacle in this regard. The measurement of effectiveness in military environment is often easy, whereas to measure success in political domain or economic development is a complex issue.28 Hence there is a need to engage all the participants from very beginning so that all have common understanding of problem and shared vision of solution. A flexible approach is also required to measure effectiveness of various initiatives.29

Departmentalism

Once the common understanding of the problem, solution and effectiveness is developed among all the participants, departmentalism is the next impediment in achievement of successful WGA. Martin Painter discusses the stovepipe thinking and ‘silo’ attitude regarding bureaucratic politics in Australia.30 He discusses how various departments and agencies pursue their own agenda in detached and discrete ways without due regards to outcome of WGAs. Certain departments often engage in ‘turf war’ to secure financial resources, staff allocations and political mileage for the continuation of various programmes or survival of their departments.31 Unfortunately, there is a tendency in few individuals in the departments to expand and get more resources for their departments even though it may not be in the best interest of the nation or coalition. This kind of narrow approaches hampers the team spirit in WGA initiatives.32 Because all departments try to protect their own positions and status at national level, they often compromise on the success of WGA. Middle level of bureaucracy is the most preventive of WGA. Unprepared participation, departmental rivalry, inadequate sharing of info are some of the reasons for failure of the WGA. There is a need to find and deliberate on the incentives for various departments so that they can be better incorporated into overall effort. Successful WGA requires: ‘redefining and renegotiating roles, responsibilities, relationships, accountabilities and power sharing’.33 Unless different team members do not leave their ‘tribal differences’, cohesion cannot be achieved.

Financial Resources

The method of financing departmental programs is another impediment in WGA. All departments in the government have fixed financial resources for normal operations. Additional resources are often allocated for special projects and initiatives. This creates a territorial mindset among various departments about financial resources. Few departments fear participation in the WGA due to loss of certain financial resources,34 whereas others consider their budget is being used by other departments to pursue their objectives. In order to avoid this notion, a separate and common pool of budget may be considered for any WGA.35 Apart from finance and budget at operational level, different pay and service conditions for personnel involved in the same operation also bring a monetary impediment to personnel.

System Impediments

The benefits of WGA can only be achieved if the supporting system is in place. This includes doctrinal compatibility, structure of the organization, information management systems and staff capacity. Vincent has deliberated WGA in detail to find out what are the impediments for the success of WGA.36 He asserts that since WGA is not the part of mainstream activity of the departments and all the departments are not structured to support WGA initiatives. Similarly WGA operation does not have a significant bearing on the career of personnel involved at long term basis because of insufficient policies in these domains.37 He also argues that creating new structures to support WGA may improve WGA initiatives, but it is likely to affect the existing tasks and roles of the departments.38

The different departments have different office automation systems which hinder the flow of information across all the actors involved. Different security classifications and privacy mechanisms to handle sensitive information also restrict the information to various participants. Additionally, technical incompatibility of various systems involved further complicates the problem. All these issues affect the efficient flow of information and timely decision making. Hence overall response time of the organization is also increased.39

Improper record keeping/ knowledge management and staff capacity are also part of system impediment in this regard. During a crisis, separate task forces is formed which is directly responsible to the highest levels without following the normal chain of commands. Loss of institutional memory upon dissolution of the task force is also a challenge.40 The staff capacity is another impediment in this regard. Because in WGA, different personnel are drawn from different departments with varying experience and skill, so their capacity to deal with crises is different. Mostly parent departments retain best personnel with them to run their routine operations. Moreover, turnover among the assigned personnel is also small and people are changed after 12-24 months. Hence by the time the staff members establish the contact with their respective counterpart they have to relinquish their seats. Apart from institutional memory, these factors severely affect the success of WGA.41

Organizational Culture

Culture is another significant issue in the success of WGA. Cultural differences are due to silo mentality prevalent in parent departments participating in WGA initiatives. The difference in organization culture of various agencies and departments is also relevant in this regard. Some agencies are process oriented whereas others are output oriented.42 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Defence have generally result oriented because generally their focus is on crises response. It has been observed in various WGA that the economic and finance departments are generally related to treasury and they tend to push their perspectives in various operations. On the other hand the transport area is dominated by engineers and their planning is based on their particular views. Similarly teachers form education departments and health department is occupied by health professionals. All these departments have their own particular culture to approach various problems. To benefit from the strengths of all the departments, it is necessary that the staffs are provided common thematic training and secondment is also done at various levels to achieve best level of coordination.43 These facts have been acknowledged and Australian Public Service’s (APS) efforts are concentrated on developing ‘organisational cultures and capabilities that support, model, understand and aspire to whole-of-government solutions’.44

Command and Coordination

Command and coordination of various agencies is also an impediment. Some non-military actors believe that militaries tend to take over all such initiative, whereas others deliberately avoid lead role. Both cases result in over-commitment of military forces. A clear political guidance is necessary on the role of various departments especially the need for leadership and coordination roles. The leadership role implies other departments have to follow the directions whereas the coordination role means other departments are at same level for equal relationship. It is therefore imperative to define the roles of different actors and more specifically, who has the lead role.45 Other than lead role, some departments do not feel comfortable in whole of the government operations because coordination with various agencies is time consuming. Additionally, in such a solution, many government departments will have less visibility at national and international level while others might steal the show. This may be detriment to the reputation to any organization.46

Other than attitudes, different information management system, non-availability of common operating procedure and absence of information sharing network are some of the obstacles in coordination. Insufficient level of staff security clearance and access to information for effective dialogue and deliberation are major obstacles to coordination.47 In order to solve this issue, a common operating procedure and information network can be devised. Furthermore, the problem of coordination can be resolved by secondment of officers in various agencies at the field, operational and ministerial levels. If the secondment is at the lower levels only, its effects dissipate at the strategic levels. The examples of Canada and the Netherlands are exceptions in this regards. In the Netherlands WGA to Fragile States, a development cooperation advisor was seconded to Defence whereas on reciprocal bases, Military Advisor has been seconded to Foreign Affairs. Similarly in Canada, a Military Advisor has been provided by Department of National Defence to Canadian International Development Agency.48 These secondments significantly improve the coordination levels. It is important to understand that WGA does not take place automatically at the operational level. Various governments have devised various policy frameworks and strategies to facilitate the WGA so that departments are facilitated to work in close coordination with each other. These frameworks are necessary for coordination, management and implementation to avoid the differences.

Most Significant Impediment to Whole of Government Approach

A series of case studies were examined to identify the most significant impediment in WGA. Study of Sydney 2000 Olympic Games, Australian Green House office and National Illicit Drugs Strategy recognise the cultural difference to be the major impediment in this regard.49 Each department strives to preserve its culture, structure and organization and avoid losing these characteristics for interoperability and coordination.50 The Institute of Public Administration Australia investigated various WGA operations across Australia and attached critical importance to transformation of bureaucratic culture. The study highlights

While structural, political and internal barriers are evident, bureaucratic barriers appear to be the most prominent. Given the nature of the barriers likely to be encountered, it is therefore arguable that integrated governance is about changing bureaucracy [emphasis added].51

Even NATO publications describe that NATO has been unable to achieve effective civil-military cooperation required for Comprehensive Approach. The organizational culture has been identified as major impediment in this regard. The fundamental question remained: ‘who is coordinating and who is to be coordinated’.52 Wilson summarises this situation as

Linking various types of power –diplomatic, informational, military and economic (DIME) –requires much more coordination and faces much greater challenges than just problems of jurisdiction, capacities and political inertia. One should always bear in mind that military and non-military challenges are very different in the same situations– they require different types of responsibility, ways of persuasion; technical assistance and dangers faced by various actors differ, particularly in terms of defining a common goal which has to be achieved.53

Having recognized the culture to be the major impediment in WGA, it is necessary to review the cultural differences among various actors. These differences exist between civil and military actors and within different civilian actors. Samuel P Huntington recognized, ‘The military are always happy to have more resources, but if they have to choose between more resources and more autonomy, they will choose more autonomy’.54 The military forces are prepared to respond to various crises or emergencies at short notice. Their resilience lies in surviving harsh environmental and logistic conditions, while the civilian participants are less prepared to work in adverse conditions. Militaries and aid workers have different opinion on working in the violent environment as well. Generally aid workers assume their neutrality to be their protection, whereas they need to know that their neutrality does not protect them from every combatant. Similarly, the development workers are generally tuned to stable and permissive environment for long term solution to the issues. Although combat engineers and development contractors have similar roles but both operate in different environment.55 Some aid agencies have their own cultures which focus on output rather than sustainable efforts. Fixed time frames and budget cycles result in inefficient use of resources. Rather than developing deeper understanding of the issue and participating in consultations, often their response is tailored to meet donor timelines. The pressures by external agencies and parent departments for quick assessment of the issue often inhibit the fair assessment which requires consultation of all the participants. In limited time, participants resort to their preconceived ideas and despatch the assessments which could be acceptable to the parent departments rather than what is true or yet to be assessed. Unfortunately, often these reports are far from reality.56

Operational Security (OPSEC) concept also creates difference among various contributors. There is a difference in the cultures of military and diplomatic community vis-à-vis aid workers. In military and diplomatic organizations everything is classified by default whereas the aid organizations generally lack understanding of operational security and secrecy.57 The proceedings of Helsinki seminar also emphasized: ‘the need to move from the ‘need to know’ to the ‘need to share’ approach in information sharing’.58 Information management is key to success in any WGA. It requires flexible information management strategies and leadership commitment which allow ‘a networked working environment … moving [away] from content and actor-based information exchange towards situation and context-based information exchange’.59

How to Resolve Cultural Issues

Since culture is the major impediment in success of any WGA, it is important to deliberate how to resolve cultural differences. In any WGA where the success of the initiative is dependent on the collaboration and integration of all concerned, peculiar culture of each department is to be kept in mind. It is necessary to encourage the atmosphere of ‘inclusiveness’ by accepting diverse views and approaches to same problem. ‘Without attention to the cultural dimensions of connecting Government, it is likely that whole-of-government initiatives can spiral into destructive and unproductive tension with no results’.60 The example of United States Welfare Policy also highlight that transformation of organizational cultures is necessary to achieve the desired results.61 The successful WGA requires culture of understanding and sharing horizontally between various agencies and vertically in each agency. A culture of trust and understanding can exponentially increase the effectiveness of any WGA. ‘In order to develop a true culture of cooperation and to mainstream Whole-of-Government and intra-agency coherence, it is necessary to embed coherence as a core value in our own organisations’.62 One way to improve the coherence among various contributing partners is to include the coherence in the list of mandatory reporting requirements. This will drive different departments to keep their actions aligned towards overall strategy in order to improve their reports.63

It is also important to acknowledge: ‘Culture and capability critically shape the success of whole of government activities’.64 Different agencies approach different problems according to their peculiar values and principles which may be conflicting for other participants. One such example is the values and principles of humanitarian actors’ vis-à-vis security or intelligence officials. It is important to be aware of these differences to achieve the optimum solution.65 WGA may involve initiatives where different individuals are working in close coordination physically or they may be operating on same information domain with minimum interaction physically. In both cases, significant time is required to develop harmonious working relationships especially where physical interaction is minimal. The participants of Indigenous Trials at Wadeye arranged social gatherings to improve networking and build culture of trust and information exchange. The case study ‘reported that cultural differences became an asset when agencies built on differences to help each other’.66 In a similar attempt to develop better understanding of each other and WGA, the participants of the Sustainable Regions whole of government initiative arranged a series of seminars. Various methods of WGA and international experiences in this regard were deliberated before embarking upon assigned tasks.67 The response to Bali bombing is a good example of successful WGA in crises where different participants had little experience of working with each other. One reason for this success was the nature of crises which shaped the environment for goodwill and eliminated cultural obstacles. The framework of coordination provided by EMA enabled all the agencies to clarify roles of various actors in crisis response. The experiences of Bali crisis allowed to evaluate linkages between state and federal government disaster plans, ascertain and address hiccups in interagency coordination.68

To summarise, different organizational cultures should be recognized without limiting the capacity of WGA objectives.69 The culture of understanding can be enhanced by exposing the employees to various perspectives and organizational cultures. This will enable them to see big picture and accept diversity of views.70 All of the participants should be made aware: ‘Culture and capability can make or break whole of government endeavours’.71

Way Ahead for Pakistan

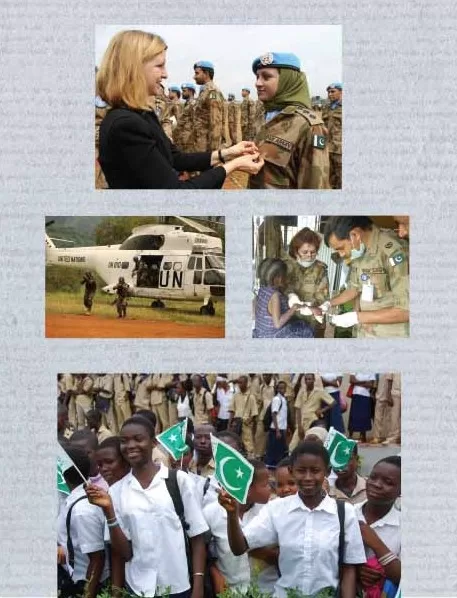

Pakistan is a developing country with limited resources. Due to security environment of the state and government structure in previous years, the military forces have primacy on state affairs whether it is national security, foreign policy or law and order. Despite limited resources, armed forces of Pakistan have developed significant combat capabilities and earned international repute due to their conduct in various national and international conflicts. Pakistan Army contingent regularly form part of UN peacekeeping forces and have earned respect due to their ethical conduct on deployments. Pakistan Navy regularly participates in international maritime exercises, seminars and operates at sea to safeguards national interests in maritime arena. Since 2004 Pakistan Navy is participating in cooperative maritime security arrangement in Indian Ocean alongwith other international navies. Since 2009, Pakistan Navy is participating in international counter piracy efforts in Gulf Aden. Pakistan Navy has commanded both task forces comprising international navies, which is a testimony of its competence. Similarly, Pakistan Air Force is also renowned for its competence in air warfare. Other than combat roles, all the services are contributing to nation building by welfare organizations, educations institutes and housing developments. All armed forces are important component of national disaster relief plan. Based on the international experiences of whole of the government approach, there is a need to utilise Pakistan military forces to resolve national problems, especially in the areas of poor security conditions. Most of Pakistani coastline is in Baluchistan where Pakistan Navy has substantial presence. Recently Coastal Command has also been raised to defend long coastline. The latest mission of Pakistan Navy also includes development of coastal communities.72 So Pakistan Navy can play an important part in development of coastal belt especially in synch with Baluchistan Comprehensive Development Strategy (2013 – 2030) initiated by UNDP.73 Based on the experiences of developed countries task forces can be formed for dedicated tasks where military may have lead role or supporting role.

In conclusion, the volatile environment after the end of Cold War leads to realize that military options are insufficient to deal with the complex challenges to security. Whole of Government Approach is one of such attempts which seeks to employ all elements of national power (diplomatic, information, military and economic) in any crises. The contribution and lead role by any element may change throughout the crises. Non-governmental actors may also be involved on case to case basis. However, despite all the benefits, it has been observed that results from any WGA cannot be easily achieved. WGA are not part of mainstream activities of any department and different departments have various approaches to the problems and their perceived solutions. The case studies of various WGA reveals that absence in planning process, departmentalism, financing arrangements, inadequate supporting systems, concept of command and coordination, and organizational culture are major impediments in this regard. The incompatible organizational cultures have been identified as the most significant impediment by Australian and NATO experiences in this regard. However, if it is recognised that culture can make or break any WGA, differences can be resolved. The example of Bali bombing, Indigenous Trials at Wadeye and Sustainable Regions WGA highlight that for a successful WGA, there is a need to develop skills, systems, culture and resources required for collaboration in the work. Keeping in view the capabilities of Pakistan armed forces and their national stature they can be involved in Whole of Government approach to various problems. The experiences of developed countries can be helpful in this regard.

Bibliography

“A Whole of Government Community Engagement Approach,how easy is it to achieve?” n.d. www.royalcommission.vic.gov.au.

Ankersen, Christopher, ed. Civil Military Cooperation in Post Conflict Operations: Emerging Theory and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge, 2008.

Biel, Maria, and Booz Allen Hamilton. Joint Irregular Warfare. USJFCOM, Joint Irregular Warfare Center, 2010.

Rintakoski, Kristiina, and Mikko Autti,. “Comprehensive Approach Seminar 17 June 2008 Helsinki.” Comprehensive Approach Trends, Challenges and Possibilities for Cooperation in Crisis Prevention and Management. Helsinki: Ministry of Defence Finland, 2008.

Coning, Cedric de, and Karsten Friis. “Coherence and Coordination: The Limits of the Comprehensive Approach.” Journal of International Peacekeeping 15 (2011): 243–272.

Connecting Government: Whole of Government Responses to Australia’s Priority. Special Report, Canberra: Management Advisory Committee, 2004.

Feaver, Peter D. Armed Servants: Agency, Oversight, and Civil Military Relations. London: Harvard University Press, 2003.

French, Julian Lindley. Enhancing Stabilisation and Reconstruction Operations. A Report on Global Dialogue between European Union and United States, Washington DC: Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2009.

French, Julian Lindley, Pau Cornish, and Andrew Rathmell. Operationalizing the Comprehensive Approach. Project Report, London: Chatham House, 2010.

Gray, Colin. “Clausewitz and the Modern Strategic World.” Contemporary Essays, n.d.

Gray, Colin S. “How Has War Changed Since the End of the Cold War?” Parameters, 2005.

Homel, Peter. “The Whole of Government Approach to Crime Prevention.” Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice (Australian Institute of Criminology), no. 287 (2004).

Hull, Cecilia. Focus and Convergence through a Comprehensive Approach: but which among the many. Department of Peace Support Operations, Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Defence Research Agency, 2010.

“Information Sharing between Government Agencies.” Policy Frame Work. Government of Western Australia, January 2003.

Kavanagh, Dennis, and David Richards. “Departmentalism and Joined-Up Government: Back to the Future.” Parliamentary Affairs 54 (2001): 1-18.

Khar, Hina Rabbani. A Comprehensive Approach to Counter Terrorism. New York, January 15, 2013.

Leat, D, K Seltzer, and G Stoker. “Interorganisational Relations and Practice.” In Towards Holistic Governance: The New Reform Agenda, by Perri 6. Palgrave Macmillan Limited, 2002.

Lennon, Alexander T.J. The Battle for Heart and Mind. Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2003.

Miščević, Tanja. “Philosophy of the Comprehensive Approach to Security.” The New Century, February 2013.

“NATO and its partners: Contributing to Comprehensive Approach.” Ten Things You Should Know about a Comprehensive Approach. Stockholm: NATO Defence College, 2008.

Rotmann, Philipp. “Built on Shaky Grounds: the Comprehensive Approach in Practice.” NATO Research Paper, December 2010.

Salber, Herbert, and Alice Ackermann. “The OSCE’s Comprehensive Approach to Border Security and Management.” http://www.core-hamburg.de. n.d. http://www.core-hamburg.de/documents/yearbook/english/09/SalberAckermann-en.pdf (accessed July 15, 2013).

Schnaubelt, Christopher M. “Operationalizing a Comprehensive Approach in Semi Permissive Environment.” NDC Forum Paper, June 2009.

Schnaubelt, Christopher M, ed. Towards a Comprehensive Approach: Integrating Civilian and Military Concepts of Strategy. NATO Defence College. Rome, March 2011.

Stewart, Jenny, and Wendy Jarvie. “Haven’t we been this way before? Evaluation and the impediments to policy learning.” Research Paper, 2008.

Swain, Rick. “Converging on Whole-of-Government Design.” Inter Agency Essay, April 2011, 11-01 ed.

Tentative Manual for Countering Irregular Threats. Quantico, Virginia: Marine Corps Combat Development Command, 2006.

Thompson, Edwina. “Smart Power.” Smart Power. Canberra: Kokoda Foundation, 2010.

“Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States.” Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2006.

“Whole of the Government.” www.nsw.ipaa.org.au/. 2005.

Windsor, Brooke Smith. “Hasten Slowly NATO’s Effect Based and Comprehensive Approach to Operation.” NATO Research Paper, July 2008.

Yates, Athol, and Anthony Bergin. Here to Help Strengthening the Defence role in Australian Disaster Management. Special Report, Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2010.

http://www.artistwd.com/joyzine/australia/strine/images/whole_of_government.jpg

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-0IbmIg5lzvE/TbmMTgeSryI/AAAAAAAAA-U/dPrzfI928SI/s200/APL-InteragencyTeaming.png

http://www.paknavy.gov.pk/

http://sprsmbalochistan.gov.pk/uploads/reports/Draft%20BCDS%20-%20Version%201.0.pdf

End Notes

2Tanja Miščević, ‘Philosophy of the Comprehensive Approach to Security,’ The New Century, February 2013, accessed July 15,2013, http://ceas-serbia.org/root/images/Tanja_Mi%C5%A1%C4%8Devi%C4%87_NEW_ CENTURY_3_eng.pdf, 17.

3‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States,’Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, accessed July 15, 2013, http://www.oecd.org/development/incaf /37826256.pdf, 17.

4‘Whole of the Government,’Institute of Public Administration Australia, accessed July 15, 2013, www.nsw.ipaa.org.au, 213.

5Christopher M Schnaubelt, ed., Towards a Comprehensive Approach: Integrating Civilian and Military Concepts of Strategy. (Rome: NATO Defence College, 2011), 4.

6Miščević, ‘Philosophy of the Comprehensive Approach to Security’, 17.

7Dennis Kavanagh and David Richards. ‘Departmentalism and Joined-Up Government: Back to the Future,’ in Parliamentary Affairs 54 (2001), 1-18.

8Edwina Thompson, Smart Power (Canberra: Kokoda Foundation, 2010), 50.

9‘NATO’s new Strategic Concept, adopted at the Lisbon Summit in November 2010, underlines that lessons learned from NATO operations show that effective crisis management calls for a Comprehensive Approach involving political, civilian and military instruments. Military means, although essential, are not enough on their own to meet the many complex challenges to Euro-Atlantic and international security’. ‘A Comprehensive Approach to Crisis Management,’ NATO, accessed July 15, 2013, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_51633.htm

10‘Whole of the Government’, 214.

11FSG Work Stream on Whole of Government Approaches, Terms of Reference Phase 1 (6.2 and 6., December 2005.

12Australian Defence Force Publication, ADFP 5.0.1, Joint Military Appreciation Process, 1-3.

13‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 10.

14‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 9.

15Athol Yates and Anthony Bergin, Here to Help: Strengthening the Defence role in Australian Disaster Management (Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2010), 1.

16‘Whole of the Government’, 215.

17‘Whole of the Government’, 213.

18‘Whole of the Government’, 215.

19‘Whole of the Government’, 227.

20‘A Comprehensive Approach to Crisis Management,’ NATO, accessed July 15, 2013, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_51633.htm.

21‘Whole of the Government’, 227.

22Miščević, ‘Philosophy of the Comprehensive Approach to Security’, 19.

23Miščević, ‘Philosophy of the Comprehensive Approach to Security’, 19.

24Miščević, ‘Philosophy of the Comprehensive Approach to Security’, 20-21.

25‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 33.

26Miščević, ‘Philosophy of the Comprehensive Approach to Security’, 17.

27‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 11.

28Miščević, ‘Philosophy of the Comprehensive Approach to Security’, 20-21.

29Peter Homel, ‘The Whole of Government Approach to Crime Prevention,’ Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice (Australian Institute of Criminology), 287 (2004): 5.

30Martin Painter and Bernard Carey, Politics between Departments : the Fragmentation of Executive control in Australian Government (St. Lucia, Q. : University of Queensland Press, 1979), 10.

31‘Whole of the Government’, 231.

32‘Whole of the Government’, 228.

33Peter Homel, ‘The Whole of Government Approach to Crime Prevention,’ 5.

34‘Whole of the Government’, 229.

35‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 11.

36Vincent, ‘Collaboration and Integrated Services in the NSW Public Sector’, Australian Journal of Public Administration, vol. 58, no. 3, 50–54.

37‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 30.

38‘Whole of the Government’, 227.

39‘Whole of the Government’, 230.

40‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 32.

41‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 35.

42‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 8.

43‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 35.

44‘Whole of the Government’, 231-232.

45‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 10.

46‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 8.

47‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 11.

48‘Whole of Government Approach to Fragile States’, 29.

49Connecting Government: Whole of Government Responses to Australia’s Priority Challenges (Canberra: Management Advisory Committee, 2004), 56.

50Philipp Rotmann, ‘Built on Shaky Grounds: the Comprehensive Approach in Practice.’ NATO Research Paper, December 2010, 4.

51Working together: Integrated Governance (IPAA and Success Works 2002), accessed July 23, 2013, http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/apcity/unpan007118.pdf

52Karl Heinz Kamp, ‘NATO’s New Strategic Concept: An integration of civil and military approaches,’ in Towards a Comprehensive Approach: Integrating Civilian and Military Concepts of Strategy. (Rome: NATO Defence College, 2011), 54.

53James Q Wilson, Bureaucracy (New York: Basic Book, 1989), 53.

54Charles D. Allen, ‘The Pit and the Pendulum: Civil-Military Relations in an age of Austerity, ‘Armed Forces Journal (2013), 20.

55Philipp Rotmann, ‘Built on Shaky Grounds’,6.

56Cedric de Coning and Karsten Friis, ‘Coherence and Coordination: The Limits of the Comprehensive Approach,’ Journal of International Peacekeeping 15 (2011): 243–272.

57Philipp Rotmann, ‘Built on Shaky Grounds’,5.

58Kristiina Rintakoski and Mikko Autti, ‘Comprehensive Approach Seminar 17 June 2008 Helsinki,’ Comprehensive Approach Trends, Challenges and Possibilities for Cooperation in Crisis Prevention and Management. (Helsinki: Ministry of Defence Finland, 2008).

59Rintakoski and Autti, ‘Comprehensive Approach Seminar’.

60‘Whole of the Government’, 231.

61Lurie and Riccucci (2003), quoted in the context of United States Welfare Policy, ‘Whole of the Government’, 232.

62Connecting Government, 45.

63Connecting Government, 45.

64Connecting Government, 45.

65Connecting Government, 45.

66Connecting Government, 51.

67Connecting Government, 51.

68Connecting Government, 114-115.

69Connecting Government, 47.

70Connecting Government, 50.

71Connecting Government, 46.

72Latest Mission of Pakistan Navy is, ‘Protect Maritime Interests of Pakistan, deter aggression at and from sea, provide disaster relief, participate in development of coastal communities and contribute to international efforts in maintaining good order at sea’. http://www.paknavy.gov.pk/

73Draft Baluchistan Comprehensive Development Strategy is available at http://sprsmbalochistan.gov.pk/uploads/reports/Draft%20BCDS%20-%20Version%201.0.pdf