Looking at the grotesque disparity between the Air Forces arrayed against each other in the Eastern wing – one PAF combat squadron versus twelve[1] of IAF – one cannot but agree that the idea of ‘defence of East lies in the West’ reflected a realistic appraisal of the grim situation by the Pakistani military strategists. With the PAF’s air element not expected to last beyond a day or two at best, and the outnumbered Pak Army hopelessly encircled by the Indian Army and Mukti Bahini, strategic compulsions demanded that a front be opened in the West at the earliest to capture Indian territory and redeem some lost honour. Occupation of Indian territory was no less important from the point of view of bargaining the release of POWs that were bound to be captured in East Pakistan, en masse. Sadly however, this line of thinking meant that Pakistani forces in the East were sacrificial lambs, and would have to submit to the inevitable sooner or later. The only challenge for the unfortunate soldiers, sailors and airmen was to delay the impending disaster as much as they could, in the dim hope of some miracle occurring on the geo-political front at the eleventh hour. If ever there was a pathetic and despondent situation at the outset of a modern day conflict, the one faced by Pakistani armed forces in East Pakistan was beyond compare.

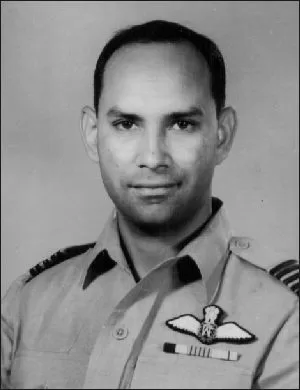

In the utterly distressing circumstances, PAF did well to designate one of its most accomplished officers to oversee operations in East Pakistan. Air Cdre Inam-ul-Haq Khan was appointed as the Air Officer Commanding East Pakistan with the dual hat of Base Commander Dacca, a few days after the military operation that commenced on the night of 25/26 March. He took over from Air Cdre M Zafar Masud, yet another outstanding officer who was relieved of his command due to an elemental disagreement with the military junta about the course of action to be followed. Masud had been doggedly advocating a negotiated political settlement in the prevailing civil disobedience movement and widespread insurgency in East Pakistan.

PAF’s Plight

In the wake of the military’s counter-insurgency operation, Air Cdre Inam-ul-Haq had some very pressing operational issues to attend to. The direct Islamabad-Dacca route, which involved flying over India, had been closed down following hijacking and subsequent blowing up of an Air India F-27 in February 1971. Pakistan was implicated for supporting the Kashmiri-origin hijackers, and the incident was used as a pretext by India to suspend overflights. Timely availability of logistics support for No 14 Squadron was, thus, rendered extremely difficult to manage across 3,000 miles, via the circuitous Ceylon (Sri Lanka) route. Spares and supplies had to be carefully conserved, even more so in view of the looming threat of all-out war.

Transfer of fuel from Narayanganj fuel depot to Dacca airfield in bowsers also became impractical due to the poor law and order situation. One C-130 was, therefore, permanently positioned at Dacca to bring in fuel supplies directly to the home base, via Colombo, till as late as end November. Reinforcements of men and material were, however, out of question once the war began.

A significant setback to PAF’s operational capability occurred when all its Mobile Observer Units had to discontinue operations, following the killing of as many as thirty five airmen, including a group of twenty who met a particularly tragic end in one incident in Mymensingh Sector. Noting that the MOUs were deployed in the field in hostile surroundings, and would have been sitting ducks for the insurgents, the previous AOC Air Cdre Masud, had ordered withdrawal of the vulnerable MOUs back to Dacca. During recovery of one of the flights consisting of twenty airmen led by the OC of No 246 Squadron, Flt Lt Safi Mustafa, it was ambushed by the Mukti Bahini. All personnel were arrested and consigned to an underground dungeon in Mymensingh Jail. The whole lot was then brutally massacred by the Mukti Bahini in an unsurprising retaliation following the military operation of 26 March. The Bengali Superintendent of the jail claimed to have been helpless in preventing the massacre as his staff was badly outnumbered. When confronted by Air Cdre Inam-ul-Haq later, he is said to have sheepishly muttered a rather strange mea culpa: “Hindu blood still runs in our veins!”[2]

Following non-availability of the MOUs, PAF’s low level early warning came to rest on a single AR-1 radar located at Mirpur, about 10 miles north-west of Dacca. With the low-looking radar constrained by an inherent line-of-sight limit of about 25 miles, the reaction time available after initial detection was barely three minutes, which was insufficient for a ground scramble. Constant patrolling by fighters was, thus, the only option for intercepting intruders before weapons release. Had the MOUs been available and deployed 50 miles out of Dacca, the reaction time could have been doubled, allowing a more economical utilisation of the limited air effort when the time came.

A high level P-35 radar that was earlier located near Dacca was withdrawn to Malir in October, to improve the coverage in southern West Pakistan. The assumption that most of the attacks against Dacca would be at low level, was not altogether unfounded, however, as things turned out.

Yet another setback suffered by the PAF soon after the 26 March operation was the loss of Bengali manpower, which was about 25% of its total strength. These Bengali officers, airmen and civilians had to be laid off as their loyalties were considered suspect. In East Pakistan, the situation was even graver as 52% of the 1,222 PAF personnel were Bengali and their services were dispensed with, leaving only 577 loyalists. Not only had the PAF to make do with shortage of manpower, it had to face the wrath of the laid-off airmen who promptly joined the Mukti Bahini, and took to harassment, ambush and sabotage. Most damaging for the PAF was the compromise of operational information that resulted when these Bengali airmen collaborated with the Indian authorities, and passed on vital secrets.

No 14 Squadron had 16 F-86E, of which only four were modified with launchers for carriage of GAR-8 Sidewinder missiles. The Unit’s aircraft strength was barely adequate for carrying out the widespread task of counter-insurgency, and its response time was not expected to be swift, particularly near the border areas.

A dual-seat T-33 was utilised for pilots’ check-outs and for maintaining instrument flying currency, while a photo reconnaissance RT-33 helped determine insurgents’ dispositions in the heavily camouflaged areas. The Rescue Squadron was made up of two Alouette-III helicopters.

Counter Insurgency Operations

Soon after the commencement of the military operation codenamed ‘Searchlight’, PAF was required to flush out those well-defended clusters of insurgents which could not be tackled by the Army alone. The months of March and April were particularly busy, during which period, 170 air support sorties were flown.

A significant air support operation took place on 15 April, to help the Army recapture Bhairab Bridge over Meghna River, which had fallen into the hands of Mukti Bahini with the active support of Indian troops. The major railway bridge was the only link between Dacca and the Sylhet-Comilla-Chittagong Sector east of Meghna, and its capture by the insurgents meant that 14 Division elements stood isolated. Equally worrying was the prospect of major grain stores on the outskirts of the nearby town of Bhairab Bazaar falling into the hands of the insurgents. It was planned that initially, a bi-directional assault by 50 SSG commandos transported by four helicopters would capture the bridge; subsequently, reinforcements would be airlifted by the helicopters shuttling between the makeshift forward base and the target area, for consolidating the operation. PAF was tasked to soften up the target before the operation and later, provide air cover for four to five hours. Accordingly, four F-86s led by Flt Lt Abbas Khattak arrived in the area at 0620 hrs, and began strafing and rocketing the insurgents’ known strongholds in Bhairab Bazaar area for about ten minutes. Under cover of the aerial onslaught, both commando teams were able to disembark close to the bridge. They assaulted it with such speed and fury that the enemy did not get any time to organise a meaningful retaliation. Bhairab Bridge was captured intact and the insurgents were completely neutralised. For the better part of the day, Army Aviation helicopters kept bringing in reinforcements, with the F-86s at hand to suppress any pockets of resistance. By dusk, the operation had culminated in resounding success.

PAF provided vital support in yet another operation on 26 April in Patuakhali, where the insurgent elements defeated two days earlier in nearby Barisal were known to have regrouped. The PAF was called upon to pound the rebels’ sanctuaries, before a company of SSG commandos and other troops landed to take control. At 0800 hrs, four F-86s, led again by the seasoned Flt Lt Abbas Khattak, pulled up for a precise rocket attack in the area. With enemy fire completely suppressed, the four troop-carrying Mi-8 helicopters were able to land and disembark the troops without a hitch. Such was the suddenness and accuracy of firepower delivered by the F-86s that Pakistani assault forces remained totally unharmed, while the insurgents were thoroughly routed in the joint operation.

No significant air support operation took place in the subsequent months, other than routine counter-insurgency missions. The advent of monsoons in June, with the dreary low clouds in intimidating attendance, curtailed flying activity for the next couple of months. As the soil started to dry out from end-September onwards, insurgent activity also started to pick up menacingly, as before. Intelligence reports also indicated movement of Indian Army formations to forward locations in what could clearly be seen as a ‘tightening of the noose’ around East Pakistan. By November, air support operations had once again spiked up considerably, with as many as 100 sorties flown during the month. These included escort missions for PIA Fokker F-27s transporting troops to the Jessore Sector, where the first Indian intrusion had taken place.

An Unlucky Strike

On 19 November, the PAF swung into action against troops and gun positions that were part of Indian 9 Division, which had brazenly violated the international border and penetrated several miles deep in Jessore Sector. Several sorties were flown against them till the afternoon of the next day. Well camouflaged tanks were spotted by an RT-33 on a recce sortie near Chaugacha, and action against them was again initiated by F-86s starting from the morning of 22 November.

In the third mission of the day, around 1530 hrs (all times EPST), three F-86s led by the Squadron Commander, Wg Cdr Afzal Choudhry, with Flg Off Khalil Ahmad as No 2 and Flt Lt Parvaiz Mehdi Qureshi as No 3, attacked a couple of tanks that had been reported in the area. Subsequent to the attack, ground control asked the leader to look for more tanks that were suspected to be concealed around. Loitering in the battlefield amounted to inviting trouble, especially when flying without radar cover. Trouble came swiftly when four ground-scrambled Gnats, of Dum Dum based No 22 Squadron, were able to sneak in and bounce the F-86 formation. At that time, the leader, Wg Cdr Choudhry, was attacking a AAA battery that was noticed to be firing at them. Pulling out of the dive, Choudhry broke into the Gnat pair flown by Flt Lt R A Massey and Flg Off S F Suarez, and managed to ward off the attack. Choudhry then reversed to take a pot shot at one of the Gnats. During a brief scrap, both Massey and Choudhry claimed firing at the other, but their aircraft remained unscathed. Massey later stated that gun stoppage prevented further firing and he had to give up the chase. Scattered, and without visual cross cover, Khalil and Mehdi fell prey to another pair of Gnats flown by Flt Lt M A Ganapathy and Flg Off D Lazarus, who picked off the two wingmen with professional ease.[3] Both F-86 pilots ejected and were captured by the insurgents, who handed them over to the Indian Army, eventually ending up as POWs. For No 14 Squadron, it was like losing the opening batsmen in the first over. Not withstanding Chaudhry’s misperception of having been outnumbered by as many as ten Gnats, the reality is that his formation was simply surprised by the nimble interceptors. It might have been instructive if Choudhry had somehow known that the two previous missions of the day had survived interception, only because they had not lingered around, and each time the Gnats had arrived in the area just a little too late.

Determined Fightback

Vacillating for a full twelve days after the Indian intrusion into East Pakistan, General Yahya and his junta reluctantly responded on the evening of 3 December by opening a front in West Pakistan. In the East, the outcome was dismally clear, but No 14 Squadron was determined to put up a fight to the last. Next morning, everyone was in high spirits, eagerly awaiting the drama that was to unfold as the curtain of fog gradually started to lift from the runway.

The first Combat Air Patrol (CAP) of the day led by Wg Cdr Afzal Choudhry took-off at first light. Perhaps the weather at IAF bases was not yet clear, so Choudhry returned without encountering any intruders. The next mission led by the much-respected Flight Commander, Sqn Ldr Dilawar Hussain, also returned without having seen any action.

Sooner the third CAP took off at 0730 hrs, a flight of three Hunters of No 37 Squadron based at Hashimara, was reported to be heading towards Tezgaon airfield from the North. Sqn Ldr Javed Afzaal, along with his wingman, Flt Lt Saeed Afzal, picked up visual contact with a pair of Hunters approaching at their 2 o’clock position. Turning in a wide arc, Afzaal easily settled behind the lead Hunter which had not yet reacted. Just as Afzaal jettisoned his drop tanks, both the Hunters broke towards the right, and after completing a 180-degree turn, rolled out on a northerly heading for home. At that moment, Afzaal came upon another unwary Hunter and promptly manoeuvred behind its tail. Like many other observers excitedly watching the dogfight from the ground, stand-by pilot Flt Lt Ata-ur-Rehman was also riveted to the fighters turning and twisting in the sky. He recalls, “I saw the lead F-86 behind two Hunters over the airfield, in line with the runway. Next, I could see leader’s bullets hitting a Hunter and it started to trail heavy smoke, though it didn’t go down as far as I could see.”[4] Afzaal too, recalls, “I saw the bullets hitting the aircraft and the last I remember is that it was still flying, trailing smoke.”[5]

Saeed, who was separated from his leader and may have been looking out for him, was oblivious of what was going on in his rear quarters. A third member of the Hunter formation, Flg Off Harish Masand, who had been straggling behind due to an earlier malfunction, emerged from nowhere and latched on to Saeed’s F-86. Firing a short, well-aimed burst from very close range, Masand was able to hit his target before it could react. Saeed ejected from the stricken aircraft but sadly, was lynched by Mukti Bahini insurgents soon after coming down by parachute.

Afzaal had, by this time, switched to a MiG-21 that he had spotted in the vicinity; it was part of a pair escorting yet another raid, this time by MiG-21s from Gauhati-based No 28 Squadron. A brief turning fight with one of the escorts ensued, while the strike aircraft went through with a successful attack on hangars and other airfield infrastructure. The MiG-21 escort then hastily disengaged to rejoin the strike aircraft on their way back.

With three different IAF formations totalling 13 aircraft having converged over Tezgaon in a matter of a few minutes, it is virtually impossible to retrace their tracks in the air.[6] What is known is that the first two formations of five Hunters, along with two MiG-21 escorts, were unable to carry out the attack in the face of determined opposition from the F-86s. It also transpires that the Hunter Afzaal had been firing at was actually from the second formation belonging to No 17 Squadron, which had reached its target somewhat early. Its pilot, Flg Off Bains, was lucky to escape with 42 bullet hits that were counted on his aircraft after landing. All the IAF aircraft were reported to have landed back. The PAF had put up a gallant fight in the first encounter of the war. An undaunted Afzaal had audaciously shown that a even a vastly large aggressor could be looked in the eye, when it was a matter of honour.

As Afzaal was being swamped by the MiGs, he had asked for immediate relief. The Staff Operations Officer, Wg Cdr S M Ahmed, who was visiting No 14 Squadron to cheer up the pilots, thought that he could lend a helping hand in the grave situation. At the spur of the moment, he decided to fly, and took along young Flg Off Salman Rasheedi as his wingman. The Squadron Commander and Flight Commander were not yet back after flying; otherwise, they might have had a different opinion about sending Ahmed up in the air, as he was not a regular flier in the squadron and had mostly been performing staff duties with the Base. Nonetheless, Ahmed’s eagerness saw the pair in the thick of action in no time. Getting airborne at about 0745 hrs, Ahmed was vectored towards a strike approaching Kurmitola airfield that lies about five miles north of Tezgaon. A Hunter flown by the Squadron Commander of No 17 Squadron, Wg Cdr N Chatrath, broke off and engaged Ahmed’s F-86. After a brief dogfight, Ahmed disengaged, but was chased right up to Tezgaon, where the pursuing Hunter finished him off. Ahmed ejected, but like Saeed Afzal in the previous mission, was hauled up by Mukti Bahini on landing. His fate was never known but it was presumed that he too met an unfortunate end at the hands of a furious mob.[7] Rasheedi, in the meantime, managed to extricate himself and landed back safely. No 14 Squadron had suffered yet another casualty but, driven by an indefatigable determination, its pilots seemed unstoppable.

The next mission of consequence was flown by Flt Lt Iqbal Zaidi and Flt Lt Ata-ur-Rahman who took off at about 0820 hrs.[8] Incidentally, Ata was a Bengali pilot who had opted to stay on with the PAF and had been cleared to fly only a week earlier, after many months of pleading with the authorities to quash his grounding. Zaidi and Ata had barely picked the gears up when four Hunters were spotted pulling up for an attack on the airfield. On leader’s instruction to split and take on a pair each, Ata was quick to position behind one of the Hunters. Closing in to a textbook range of 2,000 feet and ready to open fire, he was abruptly warned by Killer Control about two Hunters perched on his tail. Breaking viciously to ward off their attack, Ata was horrified to see tracers from the guns of both Hunters whizzing past his aircraft. He continued a hard turn till the Hunters overshot, tempting him to reverse his turn and pursue them. The Hunters, however, outran Ata’s F-86 and managed to escape at treetop height. Low on fuel and barely able to keep their wits in the prevailing confusion, Zaidi and Ata hastily recovered before yet another reported raid arrived. Reflecting on the dicey mission flown four decades ago, retired Air Vice Marshal Ata-ur-Rehman credits the Killer Control, manned by Sqn Ldr Aurangzeb Ahmed, for having saved his life. He thinks that Aurangzeb played a pivotal role in many a dogfight over Dacca.

By the time Zaidi’s F-86 pair had landed, the next one was getting airborne; the time was 0845 hrs. Led by a junior Flg Off Shams-ul-Haq, with an even junior Flg Off Shamshad Ahmad as his wingman, they had been eagerly waiting for their turn to scramble since early morning. Immediately after taking-off, they were vectored by the radar onto an intruding pair, which turned out to be Su-7s as Shams spotted them promptly. Jettisoning their drop tanks, the F-86s prepared for the engagement but were surprised to see the still-laden Su-7s split and throw in a sharp turn. As Shams was manoeuvring to shake off the Su-7 which was fast turning towards his rear, he saw the other one shoot off what appeared to be two missiles in quick succession, at Shamshad’s F-86. While Shams watched the missiles swish past his No 2, he was dumbfounded to see another one being fired at his own aircraft. Shams broke into a defensive turn and was much relieved to see this missile miss its target as well. Stupefied at the strange turn the dogfight was taking, Shams immediately pulled up behind the Su-7 that was now zooming past him. Instantly selecting his guns, Shams started firing at the Su-7 which was about 1,800 feet away. Continuing the shooting till he was close enough to pick up ricochet, Shams saw the bullets land around the canopy. At this time, the heavily smoking Su-7 selected its afterburner and tried to accelerate away. Shams claimed that soon afterwards, he saw the aircraft spiral and eventually go down. He then immediately switched to the other Su-7 which was still in his No 2’s rear quarters, but it too lit afterburner and sped away. While confirmation of the Su-7 downing by Shams remains moot, the F-86s had been successful in intercepting them before weapons release. Shams and Shamshad needn’t have been bothered about the flurry of missiles launched at them, as these were 57-mm unguided ground attack rockets cleverly fired off by the Su-7s when their mission stood aborted after being intercepted.[9]

Barely finished with shaking off the menacing Su-7s, Shams heard the radar controller call out that there were four Hunters turning for them. Outnumbered this time, Shams decided to split so that each F-86 was to engage a pair of Hunters, while foregoing mutual cross cover. To Shams’ good luck, the pair he was engaged with, also split up, and one of the Hunters inexplicably pulled away out of sight. Shams then manoeuvred behind the other Hunter and managed to close in to 600 feet before opening up with his six guns. Accurate fire got the Hunter smoking and a few seconds later, he saw the pilot eject out of the stricken aircraft.

Looking around for his wingman, Shams was more than relieved to spot Shamshad firing at a Hunter. At this time, the radar called out the position of another bogey and Shams was able to spot it in a few seconds. Apparently warned about his presence by the other Hunters, Shams saw his quarry diving down in a westerly direction towards West Bengal. With his bullets spent, Shams decided to use the Sidewinder missile, which he had earlier decided not to use due to its uncertain performance in a tight-turning dogfight. Crossing well about ten miles into Indian territory, Shams was able to close in to a mile behind the Hunter. Getting down below his target, Shams heard the unexpected growl of the seeker head at tree-top height, and let off the missile. According to Shams, “the aircraft immediately turned into a ball of fire like a napalm explosion. I saw the pilot being thrown out at an angle of 45 degrees to the right.” Shams then orbited over the area and directed the radar controller to mark his position so as to be able to apprehend the downed Hunter pilot, if possible.

At the limits of their endurance, Shams decided to recover back, and asked his No 2 to land first. Subsequently, as Shams was setting up for his landing, he saw a Hunter to his left side. Trouble seemed no end as Shams was out of ammunition; in a show of bravado, he broke off and chased the Hunter for several minutes while Dacca scrambled another pair. When yet another raid was reported by the radar, Shams thought it wise to grab the first opportunity to land back.

Just two hundred feet from the landing threshold, Shams couldn’t believe his ears when the radar controller’s radio crackled a warning about two intruders 8,000 feet behind him. If he continued with the landing, Shams thought to himself, he was sure of presenting his aircraft as an easy target to be shot at in merry good time. Instead, he peeled off from the landing approach, cleaned up his aircraft configuration and broke into a MiG-21 that he saw less than a mile behind. Turning hard into the MiG with whatever little speed he had been able to build up, Shams managed to force an overshoot but his quarry accelerated away. Going by Killer Control’s instructions to the leader of the new F-86 pair that had just taken off, Shams was able to pick up the engagement nearby. However, with his fuel tanks almost dry, Shams finally came in for a long overdue landing.

In a matter of a few gut-wrenching minutes, the rookie F-86 pilots had managed to ward off attacks by three successive formations. It was a wonder, not only that they survived an incessant onslaught by eight aircraft but, that they were able to keep their wits and managed to shoot at several of them. Sqn Ldr K D Mehra of Dum Dum based No 14 Squadron was one of Shams’ victims, who ejected near Dacca and was able to evade capture with the help of the omnipresent Mukti Bahini. Details of Shams’ second Hunter victim are hard to come by but, going by his story of having seen his victim eject inside Indian territory, followed by an orbit over the location for a radar fix, his claim may not be totally unfounded. Shamshad’s victim, which was last seen by ground observers to be trailing smoke, is considered as a ‘damage’. [10]

At about 0930 hrs, the next F-86 pair, led by Flt Lt Schames-ul-Haq – no Teutonic connection, as his name might suggest – with Flg Off Mahmud Gul as his wingman, took off for their turn to participate in the aerial drama that had been going on ceaselessly for the last two hours. Scanning the skies, they picked up a pair of Hunters in battle formation and pulling up for the attack over Tezgaon airfield. One of the Hunters broke off and started to tangle with Schames’ F-86, while the other continued with its strafing attack, with Gul in trail. Gul continued to chase his prey, but lost visual as he pulled up to avoid getting in line of the Hunter fighting with Schames. Instead of a futile chase, Gul broke off and looked for his leader who was engaged in a dogfight right overhead Dacca. Gul settled behind his leader to keep his tail clear, and intently watched the scissoring fighters. As expected of the slatted F-86 manoeuvring at slow speed, Schames was gaining advantage with every snip. Finally tail-on, he opened fire on the Hunter which started to trail heavy smoke. Gul’s situational awareness commentary was interrupted by Schames wondering out aloud, as to why the Hunter pilot wasn’t ejecting from his stricken aircraft. Apparently incapacitated, the Hunter pilot went down, with the aircraft in full view of onlookers. [11]

After an exciting first round in which the PAF was able to parry most of the blows, a lull prevailed till the afternoon, during which period two CAPs were flown without any encounter.[12] Around 1600 hrs, Sqn Ldr Dilawar Hussain took off with Flg Off Sajjad Noor on his wing. Soon, the radar was reporting bogies at their 11 o’clock position but neither Dilawar nor his No 2 could spot them. Suspecting that the radar had been unable to resolve the blips in close proximity as friend or foe, he did a belly check by banking to either side. To his horror, he spotted a Hunter well set to shoot at him from about 1,500 feet. Breaking into the Hunter, Dilawar was not only able to shake it off, but found it opportune to reverse and get behind it after it had overshot. Aiming carefully, Dilawar fired a short burst which set the left wing ablaze. Soon after, the pilot ejected from his burning aircraft.

Sajjad, in the meantime spotted another pair of Hunters pulling up into the sun. Intent on keeping them in sight, Sajjad forgot about his own tail, a most frequent mistake in air combat. Dilawar too, was fixated to this new sighting, and singled out one of the Hunters for a chase as it seemed to be running away. With both F-86s split and Sajjad completely engrossed in his front quarters, it was not long before his aircraft was rattled by cannon fire. The immensely destructive fusillade of the Hunter’s four 30-mm canon had spared none of its victims in the other dogfights, so Sajjad was lucky to manage an ejection. It was all the more so for Sajjad, as Wg Cdr R Sunderesan, the Squadron Commander of No 14 Squadron, had scored his kill in an accurate display of aerial gun firing, with his pipper remaining on the centre of the canopy as recorded on his film, according to IAF sources.

Dilawar’s victim, Flt Lt Kenneth Tremenheere, was picked up by the same PAF helicopter that had rescued Sajjad from the vicinity, a few minutes earlier. Tremenheere was fortunate to have a chivalrous rescue crew at hand just in time, for he had ejected near a pocket of a pro-Pakistan mob which was baying for his blood. While discussing the dogfight with Dilawar soon after his apprehension, a disconsolate Tremenheere revealed that he was the one who somehow happened to be ahead of his leader, and was visual with both F-86s at the beginning of the dogfight. His leader, who was perched somewhere behind, disallowed him to fire till he had himself spotted the hitherto unseen F-86s, a delay which turned out to be consequential for Tremenheere.

Writing on the Wall

From the IAF’s standpoint, the proceedings of 4 December have been succinctly summed up by the then OC of Gauhati-based No 28 Squadron (MiG-21), Wg Cdr B K Bishnoi, when he states that, “perhaps we were achieving little except for harassing the Pakistanis.”[13] He goes on to say that it was difficult to pick out aircraft in camouflaged shelters and then destroy them. He had suggested to the Eastern Air Command, “to make the runways unusable, thus grounding the enemy aircraft.” The decision to that effect seemed like an afterthought when it came on the evening of 5 December. Apparently it was not the foremost priority in the minds of IAF planners, as one can glean from Bishnoi’s lament.

IAF Canberras carried out night raids but failed to deposit a single bomb on Tezgaon runway or the infrastructure in the technical area. Instead, one of the stray bombs fell on the Officers’ Mess causing several casualties including a pro-Pakistan Bengali officer, Sqn Ldr Ghulam Rabbani. Another officer injured in the raid and given up for dead, was pulled out of the hospital morgue by the AOC himself.

While the IAF mulled new tactics, attacks against Tezgaon fell down considerably on 5 December, which is also evident from an absence of aerial engagements on that day. Both air forces mostly concentrated on providing air support to ground troops, though the IAF flew a couple of missions against Tezgaon, including one involving a napalm attack against AAA gun positions.

On the morning of 6 December, an air sweep mission of four F-86s, led by Sqn Ldr Dilawar, was sent up to ward off air attacks against the desperately cornered Pakistani ground troops in Comilla Sector, south-east of Dacca. The F-86s encountered four Hunters, of which one was claimed as downed by the wingman Flg Off Shamshad, though confirmation has been hard to come by. The inevitable attack on Tezgaon runway came shortly after the F-86s had landed at 1000 hrs. A formation of four MiG-21s led by Bishnoi, was able to place eight 500-kg bombs along its entire length, in an accurately delivered dive attack. The runway was hastily patched up by PAF’s diligent repair teams, but their efforts came to nought when a mid-day raid by Bishnoi’s team neutralised the runway yet again.

Just to be sure that a desperate 14 Squadron might not move its assets by road to nearby Kurmitola, it too was administered the same treatment as Tezgaon.

The night of 6 December saw virtually all personnel of Dacca Base put in their efforts at repairing Tezgaon runway. They were successful in preparing a stretch of about half the length and width of the standard runway, which was considered sufficient for F-86s to take-off in an air defence configuration. “The squadron crew was very excited and kept waiting for the first light to get airborne and challenge the enemy one more time,” recalls retired Air Marshal Dilawar.

At first light of 7 December, as 14 Squadron pilots were going to the Air Defence Alert hut, they saw a MiG-21 pulling up for an attack. Well-placed bombs resulted in bisection of the repaired stretch into two unusable halves. Dilawar says that when he went to the runway to inspect the state of damage, tears rolled down his cheeks. “The fate of East Pakistan has been decided,” he muttered to himself, sentimentally.

Escape by Aircrew

With air operations all but over for No 14 Squadron, the COC at Rawalpindi decided to put the aircrew to good use on the Western Front, where the war was in full fury. Early at 0300 hrs on 9 December, eight pilots and several other personnel who were considered indispensable to the war effort, were seen off by the AOC East Pakistan as they boarded PIA’s lone surviving Twin Otter.[14] Bravely piloted by the airline’s Captain Dara and First Officer Zia , the aircraft did a dangerous take-off from a 3,600-ft long, looping taxi track that was actually bent by 10° in three segments. The aircraft’s destination was Akyab (now known as Sittwe), a manned airfield in Burma, about 300 miles SSE of Dacca. It was surmised that the Burmese government would not be unduly obdurate in allowing a safe passage to the Pakistanis, who were at least putting up a pretence of being civilians faced with one or the other exigency of dire nature.

At daybreak, Sqn Ldr Dilawar who had stayed back, broke the news to the three remaining pilots of No 14 Squadron about the early morning exodus on-board the Twin Otter. Dilawar explained that in the event of Tezgaon runway being repaired by the Army Engineers and the MES, there was a need for some pilots to stay back for one last round. Perhaps, the brash victory roll by a MiG-21, a day after the runway was neutralised, was weighing too heavily on the authorities’ minds and it was thought that a retort might be curative. Before Ata, Schames and Shams could ask, “why us?” Dilawar came up with a bizarre reason, which could have been intensely funny if it wasn’t wartime: all of them had dark complexions, and would be able to blend in with the locals while an escape plan was engineered, after the aerial deed was done! Mercifully, the imprudence of the plan showed through in no time, and it was decided that the four pilots who remained would also leave the following day.

The AOC was again at the taxi-track at 0300 hrs next morning to see off the four pilots who were to fly off to Akyab, this time in a DHC-2 Beaver aircraft belonging to the Department of Plant Protection. With the department’s pilot by the name of Zafar in the captain’s seat, Sqn Ldr Dilawar sitting as the co-pilot, and the three other pilots in the rear, the yellow Beaver took off shakily in the darkness. The curved taxi track, which was faintly lit up by airmen with hand-held torches, complicated matters for Zafar, who was not even qualified to fly at night from a straight runway. After lift-off, the Beaver narrowly missed ramming into the ATC building, which prompted Dilawar to take over the controls for the rest of the flight.

After flying low over Chittagong Hill Tracts, the Beaver entered Burmese airspace, at which stage the pistols, ID cards and other papers were tossed overboard as the PAF officers were putting up a charade of being civilians. After a flight of about two-and-a-half hours, Dilawar called up Akyab for a landing clearance, which was denied. Nonetheless, the Beaver forced its way onto the airfield. As the Beaver taxied to the parking area, a welcome sight of the PIA Twin Otter that had arrived a day earlier, greeted them. Troops from the Burmese Army surrounded the aircraft, and its occupants were herded away to a large thatched cottage for some mild interrogation. After a week of internment in the same cottage, all Pakistani personnel were smuggled out by the Pakistani Embassy in Rangoon, in obvious collusion with the Burmese authorities. From Rangoon, they flew out to Bangkok, then to Teheran and finally, Karachi. Unfortunately, by the time the PAF aircrew reached their squadrons, the war had been over for many days.

Denial Plan

When it was all over on 16 December, the AOC directed his staff to implement what is known as the Denial Plan, ie destruction of assets so as to deny them from falling into enemy hands. Of the sixteen F-86s at the start of war, eleven remained, besides one T-33 and one RT-33, so these were earmarked for demolition by explosives at the last moment. In the event, Indian troops had moved into Dacca city and the air base was surrounded by hordes of trigger-happy Mukti Bahini. Any explosions in that tense situation were likely to result in retaliation of grave consequences. It was, therefore, decided to damage them with hammers, crowbars, etc. That a few of the F-86s (possibly five) were recovered by the newly-formed Bangladesh Air Force, and actually flown in the new colours for about two years, has generated some criticism about the rationale behind the delay in their destruction. It appears that there was hesitation in destroying them earlier due to sensitivities about the morale of airmen, who had been working most diligently on these very aircraft to keep them airworthy.

Of the two Alouette-III helicopters of PAF’s Rescue Squadron at Dacca, one had been damaged by small arms fire before the outbreak of hostilities, so it was left behind in an unserviceable state. The remaining helicopter managed to take-off for Akyab well before dawn on 16 December, with Sqn Ldr Sultan Khan and Flt Lt Rasheed Janjua at the controls. It was part of Pak Army Aviation’s staggered aerial convoy that included its three Mi-8 helicopters, one Alouette-III helicopter, and three Beavers of the Department of Plant Protection seconded to the Army. (Two more of Army’s Alouette-III helicopters flew out of Dacca later in the afternoon). All of these assets were later retrieved from Burma.[15] Besides the aircrew, there were 123 passengers, mostly women and children, all of whom made it back from Rangoon to Karachi via Colombo, in a PIA aircraft. As an aside, despite a lapse of over four decades, Pakistan owes a gracious acknowledgement to the Myanmar government for the help provided in the most difficult circumstances.

No 4071 Squadron’s AR-1 radar located on the northern outskirts of Dacca, was PAF’s only high value asset that was destroyed as per plan.

Badly outnumbered in men and material, fighting in the midst of a hostile population that was constantly betraying their locations to the Indians, and with a completely broken down communications and logistics infrastructure, the Eastern Command managed to hold out for a remarkable 26 days. Any chance of a last stand for Dacca was, however, rendered worthless when staggering territorial losses at the edge of core areas of West Pakistan had started to threaten the very existence of the country. Under the calamitous circumstances, it fell to the lot of the unfortunate Niazi to have to accept a cease-fire under dishonourable terms, and to unconditionally surrender all Pakistan Armed Forces in East Pakistan

An Ignoble End

With the PAF having lasted a mere 52 hours after commencement of IAF operations in East Pakistan, the Army was left to fend for itself without air cover. Wearied for the past eight months in the counter-insurgency role, and much bloodied since the Indian intrusion on 20/21 November, Lt Gen A A K Niazi’s Eastern Command troops had been falling back, quite literally, from a forward posture, to a last stand for Dacca. In line with the government’s objective of preventing loss of any territory on which Bangladesh could be proclaimed – unrealistic as it was – the thinned out Eastern Garrison had been defending the 1,800 miles of intensely convoluted land border with India. Niazi’s plan had the tacit approval of the General Staff at GHQ, which had looked at the complex situation from beyond a purely operational standpoint. Not withstanding the tactical merits or demerits of the plan, it can be argued that it unwittingly minimised the vulnerability of the sparsely deployed troops to enemy air attacks.

Badly outnumbered in men and material, fighting in the midst of a hostile population that was constantly betraying their locations to the Indians, and with a completely broken down communications and logistics infrastructure, the Eastern Command managed to hold out for a remarkable 26 days. Any chance of a last stand for Dacca was, however, rendered worthless when staggering territorial losses at the edge of core areas of West Pakistan had started to threaten the very existence of the country. Under the calamitous circumstances, it fell to the lot of the unfortunate Niazi to have to accept a cease-fire under dishonourable terms, and to unconditionally surrender all Pakistan Armed Forces in East Pakistan (consisting of 45,000 uniformed personnel[16], including 11,000 paramilitary forces and police) to the ‘GOC-in-C of Indian and Bangla Desh (sic) Forces in Eastern Theatre’ on 16 December 1971.

Outcome of Air Operations

The PAF in East Pakistan did not have the wherewithal to be of any consequence in a full-scale war, and it came as no surprise that it was grounded within two days, despite the heroic performance in aerial battles while it lasted. It had already outlived its utility when the war morphed from counter-insurgency against Mukti Bahini, to a full-scale Indian invasion with regular troops, mightily supported from the air.

The effort put in by No 14 Squadron, with sterling support from No 4071 Radar Squadron, can however, be looked at from an academic viewpoint as a classic performance in a fight against odds. Despite the looming futility of the exercise, there was no lack of grit and determination, with everyone contributing to the best of his professional ability. At least three enemy aircraft (and possibly four) were downed by No 14 Squadron pilots. Complementing the kills by fighters, batteries of Pak Army’s 6 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment deployed in various sectors, shot down ten enemy aircraft between 4-16 December. Against a loss of five aircraft, the PAF and the AAA element together destroyed almost three times as many Indian aircraft; this was an impressive exchange from an air defender’s standpoint, though it could do nothing to prevent the secession of East Pakistan.

End Notes

[1] IAF had deployed four Hunter squadrons, three each of MiG-21s and Gnats and one each of Su-7s and Canberras.

[2] Saga of PAF in East Pakistan by Air Mshl Inam-ul-Haq Khan, ‘Defence Journal,’ May 2009.

[3] Ganapathy shot down Khalil, and moments later, Lazarus shot down Mehdi.

[4] Interview with author.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The first Hunter formation, with a TOT of 0735 hrs, belonged to No 37 Squadron and was led by its Squadron Commander, Wg Cdr S P Kaul, with Flg Off Harish Masand and Flt Lt S K Sangar as his wingmen. This formation was escorted by two MiG-21s led by Wg Cdr C V Gole of No 4 Squadron based at Gauhati. Closely in tow was the second Hunter formation belonging to No 17 Squadron, which included Sqn Ldr Lele and Flg Off Bains. The third formation of four MiG-21s, with a TOT of 0740 hrs, belonged to No 28 Squadron and was led by Wg Cdr B K Bishnoi; it had two additional MiG-21s as escorts flown by Flt Lt Manbir Singh and Flt Lt D M Subiya. It was Subiya who kept Afzaal busy while the MiG-21 strike went through the attack on the airfield. (This information has been culled from the articles, “Air Battle over Dacca” by Polly Singh, and “Thunder Over Dacca – No 28 Squadron in December 1971” by Air Vice Mshl B K Bishnoi.)

[7] Air Mshl Inam-ul-Haq mentions that an Army Subedar saw Ahmed ejecting out and landing safely; he then saw Ahmed being mobbed by locals and Mukti Bahini, who led him away.

[8] Half an hour earlier, Flt Lt Schames-ul-haque and Flg Off Mahmud Gul had been able to intercept two Su-7s attacking the airfield, but could not shoot them down as the Su-7s accelerated away with afterburners blazing.

[9] Limited by the number of wing stations (a total of 4), the Su-7 could not carry air-to-air missiles, and the 2×30-mm cannon were its only integral safeguard.

[10] This account is largely based on an article titled, “An Unmatched Feat in the Air” by Flg Off Shams-ul-Haq, which was published in PAF’s official ‘Shaheen’ magazine in 1972.

[11] The fatal loss of two Hunter pilots of No 37 Squadron, Sqn Ldr A R Samanta and Flg Off S G Khonde over Dacca on 4 December is attributed to AAA hits in IAF citations. It is clarified that as per standing instructions, the AAA guns held fire whenever a dogfight was in progress overhead, and this was doubly ensured by Killer Control. In this case too, there is no evidence to the contrary, and it is certain that one of the two pilots fell to Schames’ guns. Samanta is the more likely victim as his mission time is closer to that of Schames’ mission.

[12] These two missions were successively led by Flt Lt Ata-ur-Rahman and Sqn Ldr Javed Afzaal.

[13] Thunder over Dacca, by Air Vice Marshal B K Bishnoi, Vayu Aerospace, 1/1997.

[14] The other Twin Otter had been destroyed by a Su-7 in a strafing attack on 4 December.

[15] The Mi-8 helicopters were flown by new Pak Army crew to Bangkok, from where these were shipped to Karachi; the Beavers and the Twin Otter were flown to China for onward shipment to Karachi; the Alouette-IIIs were airlifted by C-130 from Burma.