Introduction

For some time now, the IAF has been facing an increasing shortage of military hardware (especially fighter aircraft) for a number of reasons. These reasons include the completion of life cycle of its Soviet era inventory, the Tejas LCA “delays” and the painfully slow acquisition procedures as seen in the Hawk AJT deal. This dilemma- has led the IAF planners to look for relatively short term measures such as upgrading the old horses, bringing in new SU-30MKI aircraft and floating bids for 126 Medium Multi Role Combat Aircraft (MMRCA). A deal, which in today’s direct acquisition cost is worth approximately USD 10 billion1 — not to mention life cycle maintenance, up-gradation, allied equipment and training cost – was bound to create a lot of excitement, anxiety and heartburn both within India and among the international arms community.

The recent conclusion of the much publicized “military deal of the century” by the Indian Government has surprised a lot of quarters. That in the initial phases of bidding, the French Rafale was actually rejected (or excluded) eventually to be named as the winner of the con- tract2 puts a very interesting light on the depth and complexities of international politics and internecine fighting and distrust between the Indian organizations.

Within the Indian media, an interesting debate has ensued on the viability of this decision by IAF and the Indian government. Some pundits point out that in the face of a Chinese stealth prototype (which is to become operational within a decade) the decision by IAF to settle for a non-stealth – although highly capable air- craft to serve its airpower needs for at least next thirty years is somewhat surprising. Still others are lamenting the rejection of significant guarantees and Transfer-of-Technology (TOT) offered by the USA along with deliveries of their most modern F- 35 JSF stealth aircraft.

Considering that French Rafale succeeded against an array of heavy weight contenders such as USA’s F-16 and F-18 8 Super Hornets, European Typhoon and Russian Mig 35s etc. it is only logical for one to speculate about the extent and amount of economic, political, military and technological support pledged by the French to the Indians as an offset measure. One such assistance an all out partnership in nuclear technology field has been openly stated by the French in recent past and is viewed to be quite significant both by domestic and international analysts US g analysts. guarantees and promises of a strategic relation- ship in technological fields are somewhat viewed skeptically by the Indians (judging the past US record). However, even without this deal, the strategic US-India partnership is likely to materialize given the common rising challenge they face from China.

The overall modernization plans of the Indian military and especially IAF, of which the French deal is a significant part, is increasing economic-cum-military pressure on Pakistan. Hence a very carefully calculated response is needed by Pakistani planners to offset future implications of growing Indian air power capability that will accrue with the induction of Rafale in the IAF. That Pakistan finds itself in an exceedingly difficult economic and political situation only adds to the complexity of this calculated response. Whatever response is formulated by our planners it must also consider the dimensions of this whole equation that are being elaborated in the subsequent paragraphs.

Economic

An oft quoted Clausewitzian maxim says “War is the continuation of politics by other means”, but this brings into question “What is politics or policy? Why do we pursue it even at the cost of war?” The answer is, while war is the continuation of politics by other means q and economics is what human life is all about. Economic or financial activity is one of the basic survival functions of any human society and to secure the best possible share of the economic pie for themselves; humans at both individual and group level indulge in politics. Viewed in this perspective, any military debate becomes essen- Sally an economic debate and nowhere this debate is more important than in the case of two parties where one outmatches the other in resources and economic indicators.

The MMRCA deal has opened a window of opportunity for both India and France to boost their respective economies and is especially well poised to introduce new technologies, procedures, practices and expertise in the Indian commercial and military sector. Indians very persuasively increased the overall purchase offset margin to 50% against the usual 30% which is required by new Indian laws on every defense purchase of more than USD 70 mil- lion3. This roughly means that 50% of the total order would be spent inside India by Dassault through joint ventures, sub contracts and out- sourcing. This increase of 20% above the usual is going to give a major boost to Indian aviation and defense electronics sector on a long term basis. India went ahead with the 50% mark, and rightly so, because they thought that the size of this deal gave them extra leverage on this matter.

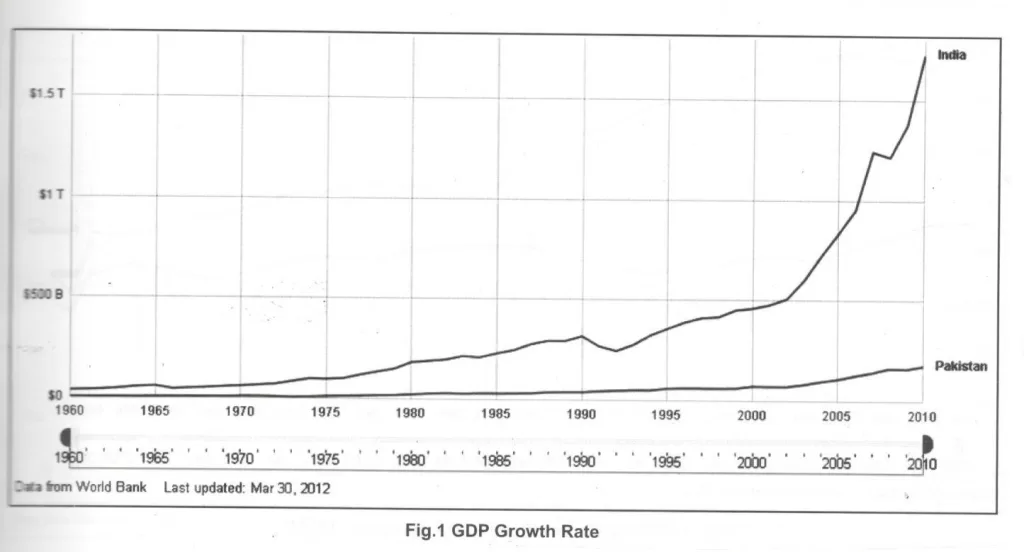

To offset the MMRCA deal, Pakistan cannot match India on a unit-to-unit basis, neither today or in the foreseeable future. Even if Pakistan could afford it, such a response would be irrational. In the last fifteen years, the Indian economic growth has shot its GDP to more than quadruple of what it was during the 90s while that of Pakistan has not risen significantly (Fig. 1). The difference in GDP growth, which shows an increase in industrial and agricultural production and services sector, has tilted entirely in India’s favour and the gap is widening with every passing year.

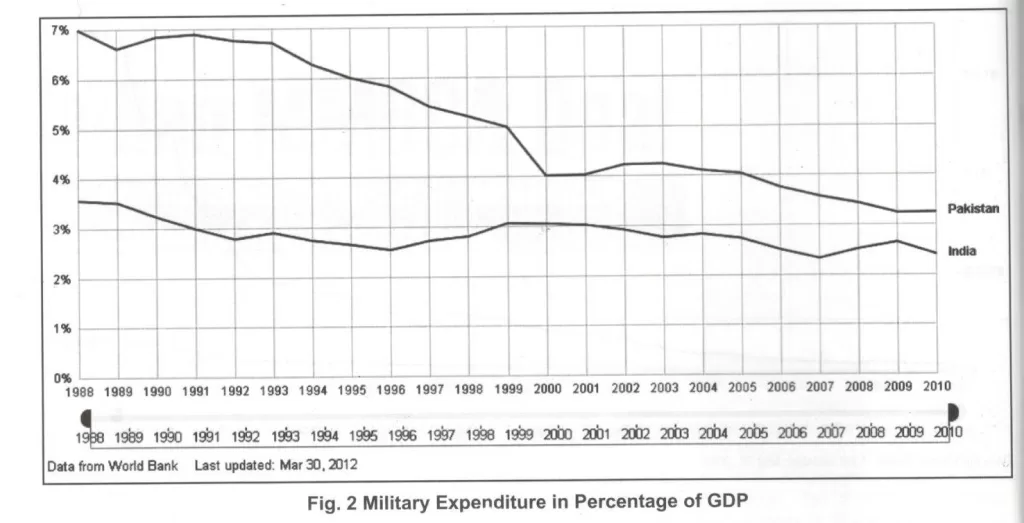

In the financial year 2011-2012, Pakistan’s defence expenditure is around 3.25% of its GDP4, which in terms of percentage is higher than the Indian spending i.e. 2.5% (Fig. 2); however, in absolute terms India out- matches Pakistan because of an extremely wide GDP margin i.e. USD 46 billion versus 06 billion respectively according to the SIPRI military expenditure database5. Hypothetically, Pakistan would have to spend approximately 25% of its total domestic out- put to match Indian cash spending, which is certain to doom an already weakened economy.

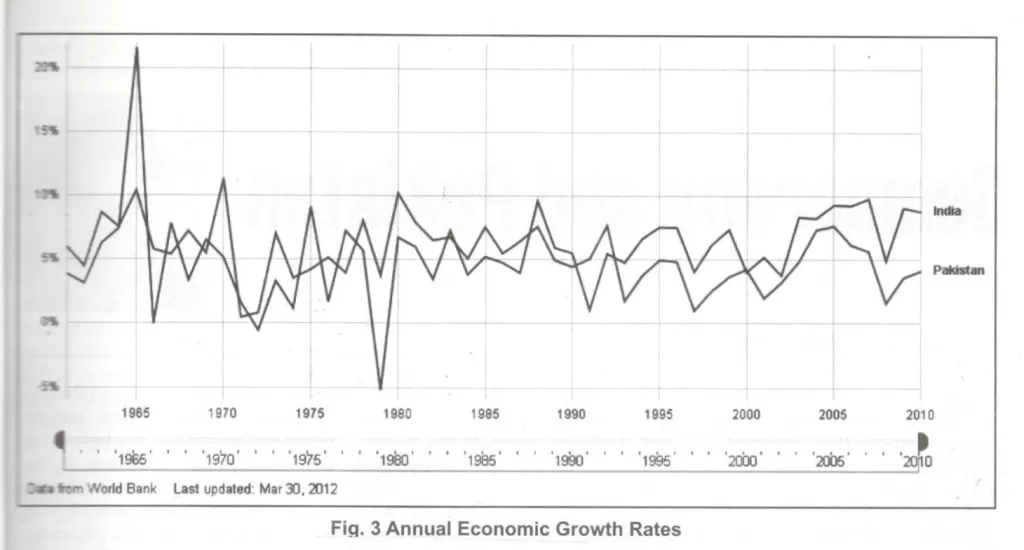

While India, with a GDP of almost USD 2 trillion (in 2012) and a sustained annual economic growth of approximately 8% (Fig. 3), can afford optimistic defence modernization plans, Pakistan would be ill advised to let the economic disparity escalate any further. Although this problem is well recognized by the planners – as witnessed by a gradual decline in overall defense expenditure even in the face of the LIC threat from the Western border I however, this decrease in military spending has unfortunately not translated into an improvement of social and corporate sector and the general economic condition remains stagnant due to varied reasons.

The successive governments need to pursue – with single minded devotion – sound, stable and consistent economic policies to at least freeze the widening GDP margin at its present level and gradually try to narrow it. For some time now, we have been trying to pursue the model of Indian defense purchase offset clause (as PIA did it in the Boeing 777 deal with the USA); however, this needs to be formalized and systematically implemented. The same offer needs to be reciprocated by Pakistani defense industries while bidding for international contracts, not only to sweeten the deal but also to build long term economic ties with smaller countries which could then enhance its political and diplomatic leverage in the future.

Political / Diplomatic (Exterior Maneuver)

In the recent past, a significant portion of Pakistan’s total defence spending has been consumed by the LIC problem in KPK and its fallout in the entire country. Finding an amicable solution to the LIC threat would ease her economic and security situation at multiple levels. Active measures need to be taken to neutralize the internal threat posed by militant groups, and to enhance Pakistan’s image in the international community as a stable and peaceful country.

It is suggested that while going for the hard kill against the domestic terror groups, a well-planned concurrent campaign of “Soft Kill” should also be initiated. The onus of responsibility in this case lies on the media, NGOs and educational institutions of Pakistan to aggressively educate the domestic population about the dangers of implosion which threatens the nation not only at socio-cultural but also at an ideological level. Pakistan needs to pacify international opinion in general and Chinese / Iranian concems in particular regarding the use of Pakistani territory by renegade groups against both countries. This can give Pakistan a much needed “get-out-of-jail-free card”, which would help soften the diplomatic pressure on Pakistan and may support its endeavors to secure politico-economic con- cessions from friendly countries.

Pakistan and India both need to de-escalate the situation with each other. However, Pakistan’s peace initiatives should not be taken as weakness by the Indian hardliners to further stiffen their position, as witnessed recently on the matter of – Siachin. Due to the economic growth and resultant international political e goodwill, India is growing bolder and more evasive on bilateral issues and Sis regrettably shoring up excessive nationalistic jingoism domestically.

The finalization of MMRCA deal clearly reveals India’s future priorities in the coming multi polar world. The MMRCA and other ongoing projects have made France the second largest defence supplier to India and have given Indians considerable leverage with the French. This augurs well for the Indian pursuit of a permanent position in the UN Security Council as two of the big five -Russia and France aligned with India, while USA and Britain both are trying for a closer relationship with her. India could well succeed in getting a permanent seat in the UN Security Council and become a regional power in the not- too-distant future, but that should not bother Pakistan excessively. If Pakistan is able to stabilize its economy, becomes an important global trading partner and once again establishes its reputation as a secure, confident and stable state, it can hold its own against a resurgent India.

End Notes

1. Boyers, James. (2012, Feb 25) Rafale Deal Reveals India’s Strategic and Political Priorities, retrieved from http://www.eastasiaforum.org

2. Nayar, K. P. (2012, Feb 06) Why India Chose Rafale, retrieved from http://www.telegraphindia.com

3. India’s M-MRCA Fighter Competition: Rafale is L-1, but No Deal Yet (2012, Feb 01), retrieved from http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com

4. World Development Indicators and Global Development Finance (2012, May retrieved 08) from http://www.google.com.pk/publicdata. Original data gathered from World Bank sources.

5. SIPRI military expenditure data- base (2012, May 10) retrieved from http://milexdata.sipri.org.