Comments

The well known expert on Asian history, geography and politics JAMES CLAVELL in his foreword to the ART OF WAR (written by SUN TZU) has expounded as follows:

“I truly believe that if our military and political leaders in recent times had studied the work of this genius, VIETNAM could not have happened as it happened; we would not have lost the war in KOREA (we lost because we did not achieve victory), the BAY OF PIGS could not have occurred, the hostages fiasco in IRAN would not have come to pass, the British Empire could not have been dismembered and in all probability, World War I and II would have been avoided – certainly they would not have been waged as they were waged, and the millions of youths obliterated unnecessarily and stupidly by monsters calling themselves generals would have lived out their lives according to their own karma. (Sum of person’s actions in one of his successive states of existence, viewed as deciding his fate in the next destiny).”

The supreme act of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.

“I find it astonishing that SUN TZU wrote so many truths twenty five centuries ago that are so applicable today. I think this little book shows so clearly what is still being done wrong, and why our present opponent is so successful in some areas (SUN TZU is obligatory reading in the SOVIET political-military hierarchy and has been available in Russian for centuries. It is the source of all MAO TSE-TUNG’s strategic and tactical doctrines.”

Tactical Dispositions

The good fighters of old first put themselves beyond the possibility of defeat, and then waited for an opportunity of defeating the enemy.

To secure ourselves against defeat lies in our own hands, but the opportunity of defeating the enemy is provided by enemy himself.

Thus the good fighter is able to secure himself against defeat.

One may know how to conquer without being able to do it.

Security against defeat implies defensive tactics, ability to defeat the enemy means taking the offensive

Standing on the defensive indicates insufficient strength attacking a superabundance of strength.

The general who is skilled in defence hides in the most secret recesses of the earth, he who is skilled to attack flashes forth from the topmost heights of heaven. Thus on the one hand we have ability to protect ourselves, on the other, a victory that is complete.

To see victory only when it is within the Ken (sight) of the common herd is not the acme (height) of excellence.

What the ancients called a clever fighter is one who not only wins, but excels in winning with ease.

The skilful fighter puts himself into a position which makes defeat impossible, and does not miss the moment for defeating the enemy.

In war the victorious strategist only seeks battle after the victory has been won, whereas he who is destined to defeat first fights and afterwards looks for victory.

A victorious army opposed to a routed one is as a pound’s weight placed in the scale against a single grain.

Energy

The control of a large force is the same in principle as the control of a few men; it is merely a question of dividing up their numbers.

Fighting with a large army is not different from fighting with a small one; it is merely a question of instilling signs and signals.

To ensure that your whole host may withstand the brunt of the enemy’s attack and remain unshaken – this is effected by maneuvers direct and indirect.

In all fighting, the direct method may be used for joining battle, but indirect method will be needed in order to secure victory.

Indirect tactics efficiently applied are inexhaustible as Heaven and Earth, unending as the flow of rivers and streams, like the sun and moon, they end but to begin anew, like the four seasons, they pass away only to return once more.

There are not more than five musical notes, yet the combinations of these five give rise to more melodies than can ever be heard.

There are not more than five primary colours, blue, yellow, red, white and black. Yet in combination they produce more hues than can ever be seen.

There are not more than five cardinal tastes, sour, acrid, salt, sweet and bitter – yet combinations of them yield more flavours than can ever be tasted.

In battle there are not more than two methods of attack – the direct and the indirect – yet these two in combination give rise to endless series of maneuvers.

The onset of troops is like the rush of a torrent which will even roll stones along its course.

The quality of decision is like the well-timed swoop of a falcon which enables it to strike and destroy its victim. Therefore the good fighter will be terrible in his onset and prompt in his decision.

Amid the turmoil and tumult of battle, there may be seeming disorder and yet no real disorder at all, amid confusion and chaos, your array may be without head or tail, yet it will be proof against defeat.

When he (the clever combatant) utilizes combined energy, his fighting men become as it were like unto rolling logs or stones. For it is the nature of a log or stone to remain motionless on level ground and to move when on a slope, if four-cornered, to come to a standstill, but if round-shaped, to go rolling down. Thus the energy developed by good fighting men is as the momentum of a round stone rolled down a mountain.

Weak Points and Strong

Whosoever first in the field and awaits the coming of the enemy will be fresh for the fight, whoever is second in the field and has to hasten to battle, will arrive exhausted.

Therefore the clever combatant imposes his will on the enemy, but does not allow the enemy’s will to be imposed on him.

By holding out advantages to him, he can cause the enemy to approach of his own accord, or by inflicting damage, he can make it impossible for the enemy to draw near.

If the enemy is taking ease, he can harass him, if well supplied with food he can starve him out, if quietly encamped, he can force him to move.

Appear at points which the enemy must hasten to defend, much swiftly to places where you are not expected.

You can be sure of succeeding in your attacks if you only attack places which are undefended. You can ensure safety of your defence if you can only hold positions that cannot be attacked.

Hence that general is skilful in attack whose opponent does not know what to defend, and he is skilful in defence whose opponent does not know what to attack.

You may advance and be irresistible if you make for the enemy’s weak points, you may retire and be safe from pursuit if your movements are more rapid than those of the enemy.

If we wish to fight, the enemy can be forced to an engagement even though he be sheltered behind a rampart and a deep ditch. All we need to do is to attack some other place that he will be obliged to relieve.

If we do not wish to fight, we can prevent the enemy forces engaging us even though the lines of our encampment be merely traced out on the ground. All we need to do is throw something odd and unaccountable in his way.

By discovering the enemy’s dispositions and remaining invisible ourselves, we can keep our forces concentrated while the enemy’s must be divided.

The spot where we intend to fight must not be made known, for then the enemy will have to prepare against a possible attack at several different points.

Numerical weakness comes from having to prepare against possible attacks, numerical strength, from compelling our adversary to make these preparations against us.

Knowing the place and the time of the coming battle, we may concentrate from the greatest distances in order to fight.

Though the enemy be stronger in number, we may prevent him from fighting. Scheme so as to discover his plans and the likelihood of their success. Force him to reveal himself, so as to find out his vulnerable spots.

In making tactical dispositions, the highest pitch you can attain to conceal them, conceal your dispositions, and you will be safe from the prying of the subtlest spies, from the machinations of the wisest brains.

All man can see the tactics whereby I conquer, but what none can see is the strategy out of which victory is evolved.

Do not repeat the tactics which have gained you one victory, but let your methods be regulated by the infinite variety of circumstances.

Military tactics are like unto water, for water in its natural course runs away from high places and hastens downwards.

So in war, the way is to avoid what is strong and to strike at what is weak. Therefore, just as water retains no constant shape, so in warfare there are no constant conditions.

He who can modify his tactics in relation to his opponent and thereby succeed in winning, may be called a heaven-born captain.

Manoeuvring

In war the general receives his commands from the sovereign. Having collected an army and concentrated his forces, he must blend and harmonise the different elements thereof before pitching the camp.

After that comes tactical maneuvering , than which there is nothing more difficult. The difficulty of tactical maneuvering consists in turning the devious into direct and misfortune into gain.

Thus, to take a long and circuitous route, after enticing the enemy out of the way, and though starting after him, to contrive to reach the goal before him, shows knowledge of the artifice of deviation.

Maneuvering with an army is advantageous, with an undisciplined multitude, most dangerous.

If you set a fully equipped army to march in order to snatch an advantage the chances are that you will be too late. On the other hand, to detach a flying column for the purpose involves the sacrifice of its baggage and stores.

Thus if you order your man to roll up their buff coats and make forced marches without halting day or night, covering double the usual distance at a stretch, doing a hundred li (2.78 modern li to a mile) in order to wrest an advantage, the leaders of all your three divisions will fall into the hands of the enemy.

The stronger men will be in front, the jaded ones will fall behind and on this plan only one-tenth of your army will reach its destination.

If you march fifty li in order to out maneuver the enemy, you will lose the leader of your first division and only half your force will reach the goal.

We cannot enter into alliances until we are acquainted with the designs of our neighbours.

We are not fit to lead an army on the march unless we are familiar with the face of the country, its mountains and forests, its pitfalls and precipices and swamps. We shall be unable to turn natural advantages to account unless we make use of local guides.

Move only if there is a real advantage to be gained. Whether to concentrate or to divide your troops, must be decided by circumstances.

Let your rapidity be that of the wind, your compactness that of the forest.

In raiding and plundering be like fire, in immovability like a mountain.

Let your plans be dark and impenetrable as night and when you move, fall like a thunderbolt.

When you plunder countryside, let the spoils be divided amongst your men, when you capture new territory, cut it up into allotments for the benefit of the soldiery.

He will conquer who has learnt the artifice of deviation. Such is the art of maneuvering.

On the field of battle, the spoken word does not carry far enough, hence the institution of gongs and drums. Nor can ordinary objects be seen clearly enough, hence the institution of banners and flags.

In night fighting, then, make use of signal-fires and drums, and in fighting by day, of flags and banners as a means of influencing the ears and eyes of your army.

Commander-in-chief may be robbed of his presence of mind. Presence of mind is the general’s most important asset. It is the quality which enables him to discipline disorder and to inspire courage into the panic-stricken.

A soldier’s spirit is keenest in the morning, by noon it has begun to flag and in the evening his mind is bent only on returning to camp.

A clever general, therefore, avoids an army when its spirit is keen, but attacks it when it is sluggish and inclined to return. This is the art of studying moods.

To refrain from intercepting an enemy whose banners are in perfect order, to refrain from attacking an army drawn up in a calm and confident array – this is the art of studying circumstances.

It is a military axiom not to advance uphill against the enemy, nor to oppose him when he comes downhill.

Do not pursue an enemy who simulates flights, do not attack soldiers whose temper is keen.

Do not swallow bait offered by the enemy. Do not interfere with an enemy returning home. A man whose heart is set on returning home will fight to the death against any attempt to bar his way and is therefore too dangerous an opponent to be tackled.

When you surround an army, leave an outlet free. This does not mean that the enemy is to be allowed to escape. The object is to make him believe that there is a road to safety, and thus prevent him fighting with the courage of despair.

Variation of Tactics

When in difficult country do not encamp. In country where high roads intersect, join hands with your allies. Do not linger in dangerously isolated positions. In hemmed-in-situations, you must resort to stratagem. In desperate position, you must fight.

There are roads which must not be followed. Especially those leading through narrow defiles, where an ambush is to be feared.

When you see your way to obtain a trivial advantage, but are powerless to inflict a real defeat, refrain from attacking for fear of overtaxing your men’s strength.

No town should be attacked which, if taken cannot be held, or if left alone, will not cause any trouble.

Even if it be your sovereign’s command to encamp in difficult country, linger in isolated positions, etc, your must not do so.

The general who thoroughly understands the advantages that accompany variation of tactics knows how to handle his troops.

Reduce the hostile chiefs by inflicting damage on them, make trouble for them, and keep them constantly engaged, hold out specious allurements and make them rush to any given point.

There are five dangerous faults which may affect a general: 1) Recklessness, which leads to destruction; (2) cowardice, which leads to capture; (3) a hasty temper, which can be provoked by insults; (4) shame and (5) over solicitude for his men, which exposes him to worry and trouble.

These are the besetting sins of a general, ruinous to the conduct of war. When an army is overthrown and its leader slain, the cause will surely be found among these five dangerous faults. Let them be a subject of meditation.

The Army on the March

We now come to the question of encamping the army and observing signs of the enemy. Pass quickly over mountains, and keep in the neighbourhood of valleys.

Camp in high places. Not on high hills but on knolls or hillocks elevated above the surrounding country. Facing the sun do not climb heights in order to fight.

After crossing a river, you should get far away from it.

When an invading force crosses a river in its onward march, do not advance to meet it in mid stream. It will be best to let half the army get across and then deliver your attack.

If you are anxious to fight you should not go to meet the invader near a river which he has to cross. Do not move upstream to meet the enemy.

In dry, level country, take up an easily accessible position with rising ground to your right and on your rear, so that the danger may be in front and safety be behind.

When you come to a hill, or a bank, occupy the sunny side, with slope on your right rear. Thus you will at once act for the benefit of your soldiers and utilize the natural advantages of the ground.

A river which you wish to ford is swollen and flecked with foam, you must wait until it subsides.

Country in which there are precipitous cliffs with torrents running between, deep natural hollows, confined places, tangled thickets, quagmires and crevasses, should be left with all possible speed and not approached. We should get the enemy to approach them while we face them, we should let the enemy have them on his rear.

When the enemy is close at hand and remains quiet, he is relying on the natural strength of his position.

If his place of encampment is easy of access, he is tendering a bait.

The rising of birds in their flight is the sign of an ambuscade. Startled beasts indicate that a sudden attack is coming.

When there is dust rising in a high column, it is sign of chariots advancing, when the dust is low but spread over a wide area, it betokens the approach of infantry.

The sight of men whispering together in small knots or speaking in subdued tones points to disaffection amongst the rank and file.

To begin by bluster, but afterwards to take fright at the enemy’s numbers, shows a supreme lack of intelligence.

If our troops are no more in number than the enemy, that is amply sufficient, it only means that no direct attack can be made.

Soldiers must be treated in the first instance with humanity, but kept under control of iron discipline.

If in training soldiers commands are habitually enforced, the army will be well-disciplined, if not, its discipline will be bad.

If a general shows confidence in his men but always insists on his orders being obeyed, the gain will be mutual.

Terrain

We may distinguish six kinds of terrain, to wit: 1) accessible ground, 2) entangling ground, 3) temporizing ground, 4) narrow passes 5) precipitous heights and 6) positions at a great distance from the enemy.

Ground which can be traversed by both sides is called accessible. With regard to ground of this nature, be before the enemy in occupying the raised and sunny spots, and carefully guard your line of supplies. Then you will be able to fight with advantage.

Ground which can be abandoned but is hard to re-occupy is called entangling. From a position of this sort, if the enemy is unprepared, you may sally forth and defeat him. But if the enemy is prepared for your coming, and you fail to defeat him, then return being impossible, disaster will ensue.

When the position is such that neither side will gain by making the first move, it is called temporizing ground.

With regard to narrow passes, if you can occupy them first, let them be strongly garrisoned and await the advent of the enemy.

With regard to precipitous heights, if you are before hand with your adversary, you should occupy the raised and sunny spots, and there wait for him to come up.

When the common soldiers are too strong and their officers too weak, the result is insubordination. If the officers are too strong and the common soldiers too weak, the result is collapse.

When the general is weak and without authority, when his orders are not clear and distinct, when there are no fixed duties assigned to officers and men, and the ranks are formed in a slovenly haphazard manner, the result is utter disorganization.

There are six ways of courting defeat: 1) neglect to estimate the enemy’s strength, 2) want of authority, 3) defective training, 4) unjustifiable anger, 5) non-observance of discipline and 6) failure to use picked men, which must be carefully noted by the general who has attained a responsible post.

If fighting is sure to result in victory, then you must fight, even though the ruler forbid it; if fighting will not result in victory then you must not fight even at the ruler’s bidding.

Regard your soldiers as your children, and they will follow you into deepest valleys, look on them as your own beloved ones and they will stand by you even unto death.

If we know that our own men are in a condition to attack, but are unaware that the enemy is not open to attack, we have gone only halfway to victory.

If we know that the enemy is open to attack but we are unaware that our own men are not in a position to attack, we have gone only halfway to victory.

Hence the saying, ‘If you know the enemy and know yourself, your victory will not stand in doubt, if you know Heaven and know Earth, you may make your victory complete.’

The Nine Situations

The art of war recognizes nine varieties of ground (1) dispersive ground, 2) facile ground 3) contentious ground, 4) open ground 5) ground of intersecting highways 6) serious ground 7) difficult ground 8) hemmed in ground and 9) dangerous ground.

When a chief is fighting in his own territory it is dispersive ground.

When he has penetrated into hostile territory, but to no great distance, it is facile ground.

Ground, the possession of which imparts great advantage to either side, is contentious ground.

Ground on which each side has liberty of movement is open ground.

Ground which forms the key to three contiguous states so that he who occupies it first has most of the Empire at his command, is ground of intersecting highways.

When an army has penetrated into the heart of a hostile country leaving a number of fortified cities in its rear, it is serious ground.

Mountain forests, rugged slopes, marshes and fens – all country that is hard to traverse is difficult ground.

Ground which is reached through narrow gorges and from which we can only retire by tortuous paths, so that a small number of the enemy would suffice to crush a large body of our men: this is hemmed-in ground.

Ground on which we can only be saved from destruction by fighting without delay is desperate ground.

Rapidity is the essence of war. Take advantage of the enemy’s unreadiness, make your way by unexpected routes and attack unguarded spots.

On dispersive ground, fight not. On facile ground, halt not, On contentious ground, attack not.

On open ground, do not try to block the enemy’s way. On ground intersecting highways, join hands with your allies.

On serious ground, gather in plunder. In difficult ground, deep steadily on the march. On hemmed-in ground, resort to stratagem. On desperate ground, fight.

Carefully study the well being of your men, and do not overtax them. Concentrate your energy and hoard your strength.

Soldiers, when in desperate straits lose the sense of fear. If there is no place of refuge, they will stand firm. If they are in the heart of a hostile country, they will show a stubborn front. If there is no help for it, they will fight hard.

A skilful general conducts his army just as though he were leading a single man, will-nilly, by the hand.

It is the business of a general to be quiet and thus ensure secrecy, upright and just, and thus maintain order.

At the critical moment, the leader of an army acts like one who has climbed up a height and then kicks away the ladder behind him. He carries his men deep into hostile territory before he shows his hand.

He burns his boats and breaks his cooking pots, like a shepherd driving a flock of sheep, he drives his men this way and that, and none knows whither he is going.

Bestow rewards without regard to rule, issue orders without regard to previous arrangements, and you will be able to handle a whole army as though you had to do with but a single man.

The Attack By Fire

There are five ways of attacking with fire. The first is to burn soldiers in their camp, the second is to burn stores, the third is to burn baggage-trains, the fourth is to burn arsenals and magazines, the fifth is to hurl dropping of fire amongst the enemy.

In order to carry out an attack with fire, we must have means available, the material for raising fire should always be kept in readiness.

There is a proper season for making attacks with fire, and special days for starting a conflagration.

The proper season is when the weather is very dry, the special days are those when the moon is in the constellation of the sieve, the wall, the wing or the crossbar, for these four are all days of rising wind.

The prime object of attacking with fire is to throw the enemy into confusion. If this effect is not produced, it means that the enemy is ready to receive us. Hence the necessity for caution.

When the force of the flames has reached its height, follow up with an attack, if that is practicable, if not, stay where you are.

If it is possible to make an assault with fire from without, do not wait for it to break out within, but deliver your attack at a favourable moment.

When you start a fire, be to windward of it. Do not attack from leeward.

In every army, the five developments connected with fire must be known, the movements of the stars calculated, and a watch kept for the proper days.

But a kingdom that has once been destroyed can never come again into being, nor can the dead ever be brought to life.

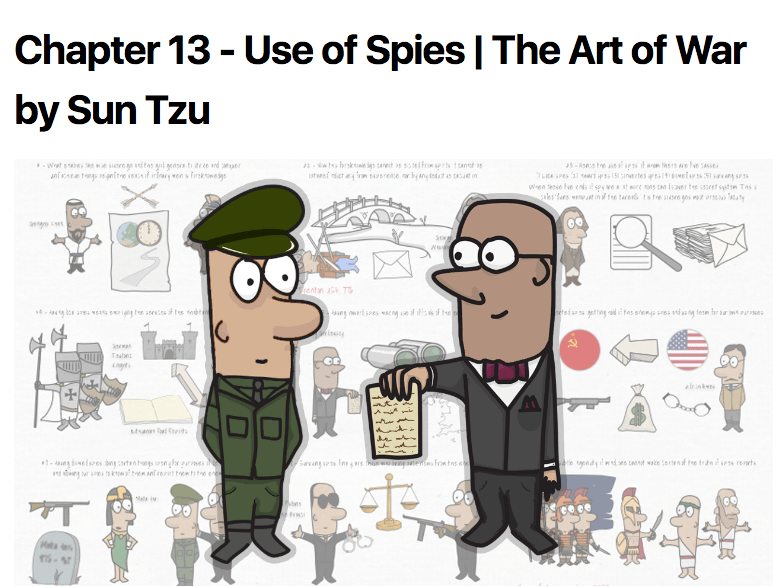

The use of Spies

Raising a host of a hundred thousand men and marching them great distances entails heavy loss on the people and a drain on the resources of the State. The daily expenditure will amount to a thousand ounces of silver. There will be commotion at home and abroad, and men will drop down exhausted on the highways. As many as seven hundred thousand families will be impeded in the labour.

Hostile armies may face each other for years, striving for the victory which is decided in a single day. This being so, to remain ignorant of the enemy’s condition simply because on grudges the outlay of a hundred ounces of silver in honours and emoluments, is the height of inhumanity.

One who acts thus is no leader of men, no present help to his sovereign, no master of victory.

Thus, what enables the wise sovereign and the good general to strike and conquer and achieve things beyond the reach of ordinary men, if foreknowledge. That is knowledge of the enemy’s dispositions and what he means to do.

Knowledge of the enemy’s disposition can only be obtained from other men.

Hence the use of spies, of whom there are five classes viz 1) local spies 2) inward spies 3) converted spies 4) doomed spies and 5) surviving spies.

Having local spies means employing the services of the inhabitants of a district. Win people by kind treatment and use them as spies.

Having inward spies: making use of officials of the enemy. Worthy men who have been degraded from office, criminals who have undergone punishment, men who are aggrieved at being on insubordinate positions, or who have been passed over in the distribution of posts, fickle turncoats who always want to have a foot in each boat.

Having converted spies means getting hold of the enemy’s spies and using them for our own purposes. By means of heavy bribes and liberal promises detaching them from the enemy’s service and inducing them to carry back false information as well as to spy in turn on their own countrymen.

Having doomed spies means doing certain things openly for purpose of deception and allowing our own spies to know of them and report them to the enemy.

Surviving spies, finally are those who bring back news from the enemy camp.

All communication with spies should be carried on ‘mouth-to-ear’. Spies are attached to those who give them most, he who pays them ill is never served. They should never be known to anybody, nor should they know one another. When they propose anything material, secure their persons or have in your possession their wives and children as hostages for their fidelity. Never communicate anything to them but that what is absolutely necessary that they should know.

In order to use them, one must know fact from falsehood and be able to discriminate between honesty and double dealing.

If a secret piece of news is divulged by a spy before the time is ripe, he must be put to death together with the man to whom the secret was told.

Whether the object be to crush an army or to storm a city, or to assassinate an individual, it is always necessary to begin by finding out the names of the attendants, the aides-de-camp, the door keepers and sentries of the general in command. Our spies must be commissioned to ascertain these.

The enemy’s spies who have come to spy on us must be sought out, tempted with bribes, lead away and comfortably housed. Thus they will become converted spies and be available for our service.

It is through the information by the converted spy that we are able to acquire and employ local and inward spies.

It is owing to his information, again, that we can cause the doomed spy to carry false tidings to the enemy.

Spies are a most important element in war, because on them depends an army’s ability to move.

An army without spies is like a man without ears or eyes.

Conclusion – Recommendations

The art of war is of vital important to the State. It is matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin. Hence it is a subject of inquiry which can on no account be neglected by any one of us, today and tomorrow.

I admit my ignorance that only a few sayings of Sun Tzu were known to me. My inquisitiveness about military history is also known to my brilliant son-in-law Group Capt SYED NADEEM SABIR who during his last year’s visit to CHINA, brought for me a beautifully wrapped-in-velvet cloth calendar of wooden pieces (24″x6″) depicting the headings of 13 chapters of Sun Tzu’s Art of War in English and in Chinese on the reverse side. Subsequently NADEEM presented me with a complete book. I found it simple (not difficult like the ‘WAR’ by CLASUWITZ or the CONDUCT OF WAR by FULLER), brief (not at the cost of clarity) and easily understandable. Needless to say that it is a unique wealth of military strategy, tactics and other connected subjects. I am thoroughly imbued with gratitude for this enviable copy of the book.

Part II “Some Selected Sayings of the Genius SUN TZU’ copied from the Art of War has become rather lengthy for an article but while reading the thirteen chapters it was difficult to ignore many sayings. Perforce I deleted some of the explanations, example and historical events. I hope my humble effort will draw the eyes of some of our learned readers and particularly of students of military history. For promoting the study of this classic document on war I submit the following recommendations:

A brief of the important sayings of SUN TZU’s ‘The Art of War’ should be prepared by an expert committee of the IGT&E Branch of GHQ. It should be distributed to all serving officers.

Some chapters of The Art of War should be included in the syllabus of promotion, staff college entrance and other professional examinations. This task should also be assigned to an expert committee.

Some sayings of SUN TZU, quoting identical events of our own wars, should also be discussed with students attending professional courses in military institutions.

An expert committee should also sift examples from the many famous decisive battles of ISLAM, highlighting strategy and tactics, as advocated/ recommended by SUN TZU in his book.

Concluded