The morning of 7th of December was quite hazy, particularly at lower altitudes where the dust of Punjab plains mingled with the moist, cold air, giving the sky a murky appearance. It was just four days since the 1971 Indo-Pak War had broken out. While the PAF was conserving its air effort in the early stages of war, IAF’s intensity of air operations was building up at a fast pace.

Flg Off Man Mohan Singh was ferrying a Gnat from Halwara, to beef up a detachment of No 2 Squadron at Amritsar where these aircraft were deployed to perform air defence duties. As Mohan was nearing home, the controller at Amritsar Radar asked him to delay his landing while a pair of Su-7s took off. After holding off for a few minutes, Mohan resumed a northerly heading for the Base.

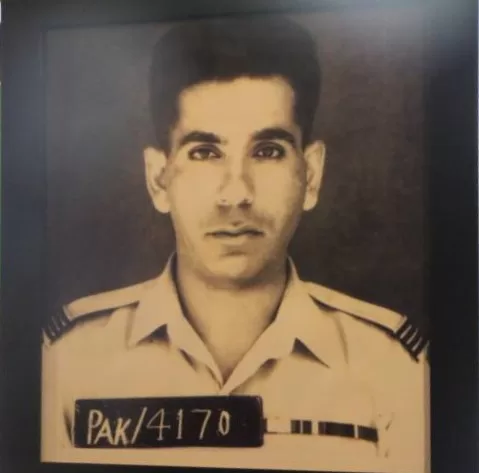

Sqn Ldr Farooq Haider, a veteran of the ’65 War, was sitting as the duty controller in No 403 Radar Squadron which was located in the outskirts of Lahore. Watching the radar scope intently, he had picked up a blip as it approached Tarn Taran, south of Amritsar. With the adversary nearing its home Base, Farooq had to act fast. He commenced the interception with steady instructions on the radio.

“Your target now over Tarn Taran, heading 360; do not acknowledge.”

“Target 20 (degrees) right, five (miles), turn hard left 360, do not climb; do not acknowledge.”

“Target 12 o’clock, two (miles), go full bore; do not acknowledge.”

“Okay, target is one mile ahead …”

The IAF had been expecting PAF fighters to sneak in below radar cover. Thus, to be doubly sure about any undetected intruders, the IAF used a capability that it was well equipped for – eavesdropping into pilot-controller conversation. Listening in to what was going on, the IAF controller was completely dumbfounded at the development, for he had not yet picked up any blip on his scope. All of a sudden, he frantically shouted on the radio to announce the presence of interceptors in the Gnat’s rear quarters! It was no surprise, therefore, that the controller’s warning to Mohan sounded eerie, as if a spectre was being reported. With the interceptors’ distance rapidly reducing and shooting down of the Gnat almost a certainty, the controller gave a panic ‘break’ call. Mohan reacted as any fighter pilot would have done in that situation. He yanked back on the control column and threw in a very tight turn to shake off his pursuers.

Farooq noticed that the blip had disappeared from the radar screen shortly after manoeuvring had commenced. Normally, he would have enquired about the fate of the target from the interceptor pilots within moments of the shooting. This time, however, he had to be discrete. “Maintain radio silence and recover at low altitude,” he called out. Meanwhile, Farooq and his fellow controllers wondered if the vanished blip meant that the aircraft had landed at its Base?

India’s Official History of Indo-Pak War, 1971, published thirty years later, covers the air operations with a diary of action which includes important events like air raids, aerial victories and losses on both sides. A keen reader would notice acknowledgement of the loss of a Gnat on 7th December 1971 in which, “the pilot tried to take evasive action when warned of Pak aircraft in the vicinity. He lost control and crashed .” The only inaccuracy with the account is that Pakistani aircraft were nowhere near!

Standing CAPs were a rare commodity due to excessive demands on PAF’s limited assets. Farooq had, therefore, reacted to the emergent situation in a most ingenuous way. He impulsively decided to fake an interception in the knowledge that his calls would be monitored. The thrill of playing a prank was better than getting frustrated at the sight of an enemy blip pacing away unscathed. In the event, Farooq’s trick resulted in a bargain of great value, which can be gleaned from the amazing fact that not a gallon of fuel was expended, nor was a single bullet fired. Arguably, it stands as the cheapest kill of air warfare.